|

Due to being tired and stuff I've put off writing about this for a couple weeks, and now it's rather old news and the LDS Church has already moved on to its next controversy, this time pissing off its right-wing members by distancing itself from Operation Underground Railroad founder Tim Ballard over alleged predatory sexual misconduct that's no worse than Joseph Smith's. But this news blew up in my circles a couple weeks ago, and I thought I should do my part within my maddeningly limited capacity to spread it further. As I said recently after watching The Last Voyage of the Demeter, how can I possibly be scared of this when real monsters look like this? These women were both arrested and charged with six counts of felony child abuse after an emaciated child with ropes on his wrists and ankles escaped from their secluded house and asked a neighbor for food and water. On the right is Ruby Franke, a Mormon mother of six who ran the YouTube channel 8 Passengers, which I had never heard of until this news came out, but which was apparently very popular among people who have nothing better to do than watch other people's families do normal family things. Granted, they weren't all normal. Ruby has some twisted ideas about discipline. Like a true Republican, she believes that things like food and beds are privileges, and appeared to take a sadistic level of pleasure in withholding them from her children to teach them lessons. She let her six-year-old daughter go hungry at school and took away her teenage son's bed for months. People raised concerns about her over the years and called Child Protective Services multiple times, but nothing happened to her and her channel's popularity continued. So of course many are wondering, is she a terrible person because she's a Mormon, or is she a terrible person who just happens to be a Mormon? The LDS Church covers up child abuse, silences the victims, and protects the abusers, but it doesn't condone child abuse as such. No normal member would think that what she did is okay. Yet the church does condition people to believe that their irrational or delusional thoughts come from the Holy Ghost, so that may have been a significant factor in her justifying her unorthodox methods. And frankly, it often frames trials and deprivations as God intentionally giving us "learning experiences." Heavenly Father, the perfect all-loving parent, allows billions of his children's basic human needs to go unmet every day so they can grow and become more like him. Why is it divine wisdom when he does it but child abuse when Ruby Franke does it? The one on the left, Jodi Hildebrandt, is much worse. If Ruby Franke is Iran, Jodi Hildebrandt is Afghanistan. They entered into a close relationship after Ruby gave up her YouTube channel to join Jodi for a weird pseudo-therapy program called Connexions. A very close connection. There's been a lot of speculation that they're more than business partners and more than friends, and while it is homophobic to assume that raging homophobes like Jodi are closeted, it's hard to avoid that kind of speculation when she sits so close to Ruby and strokes her leg. Anyway, Jodi is a straight-up sociopath, pathological liar, and gaslighter who used her therapy practice to destroy marriages and families. She reminds me of a neighbor I used to have who claimed she could read people's auras and see the future, then drove people apart with lies and manipulation. In this case, her influence undoubtedly made Ruby worse. My understanding is that she was the one who actually carried out the physical abuse of Ruby's children that got her arrested, while Ruby was arrested for living in the same house and knowing about it and not doing anything. Jodi is also Mormon, and in her case, the church has a lot more direct and obvious culpability. She isn't entirely in sync with it either - it's run almost exclusively by men, while she holds all men in contempt - but she worked with apostles such as Richard G. Scott to design its addiction recovery program, she was on its list of approved therapists, and she was recommended by countless bishops to help with so-called pornography addiction. The way she pathologized masturbation and portrayed anyone who did it once a month as an addict in Satan's grip was at odds with legitimate science and therapeutic practices, but very much at home with Mormon teachings. People assert, and I have no reason to doubt, that Mormon therapists throughout Utah, Idaho, and Arizona are still doing the same thing, though they aren't on the same level of pure intentional evil as Jodi Hildebrandt. I don't know who needs to hear this, but masturbation is a normal, healthy, and almost universal activity that evolved in our primate ancestors as much as forty million years ago. I think, too, that Mormon clients were more susceptible to Jodi's psuedoscience because they're taught to base their worldview on feelings. After the arrests, Jodi's niece Jesse (they/them) came forward to share how she physically and emotionally abused them while their family was making them live with her for an extended time. Jesse's family didn't know the extent of what was going on and didn't want to. Jesse's family got upset with them for creating controversy by publicly criticizing Jodi over a decade ago. The LDS Church is not blameless for that. It teaches Mormons that "contention is of the devil" and that negative emotions come from Satan, so many of them are very immature about conflict and treat calling out unacceptable behavior as a bigger sin than the unacceptable behavior. I hope Jesse's parents and siblings have all seen this interview and done some soul-searching. Then a formerly anonymous client, Adam Paul Steed, shared his story in greater detail than before. Jodi got her license suspended for a while in 2012 after she told the BYU Honor Code office things about him that, even if she hadn't made them up, would have been confidential. (Of course, the BYU Honor Code office has its own long history of crossing legal and ethical boundaries to persecute students, which a few years ago resulted in BYU's police department becoming the only one in Utah history to be threatened with decertification.) Jodi destroyed Adam's marriage by convincing his wife that he was a sexual predator and a threat to their children. The best part? She apparently did it on behalf of the late Elder Harold G. Hillam, a high-ranking Mormon and Boy Scout leader who held a grudge against Adam after his role in getting the statute of limitations for child abuse victims in Idaho extended and getting Boy Scout leaders who abused children removed. With the exception of Elder Harold G. Hillam, I wouldn't say that LDS leaders are personally to blame for this abuse. I would say that they actively fostered an environment where it could happen, and they proved themselves yet again to be horrible judges of character and no more "inspired" than anyone else. The LDS Church deserves the negative publicity this story has brought it and will bring it for years to come.

0 Comments

Nobody really knows what happens after we die. I don't care what people believe, though I get pretty annoyed when atheists assert as a fact that there's nothing after we die. They're supposed to only believe stuff that's empirically verifiable, yet here they are asserting something that they clearly haven't verified because they aren't dead. And there's actually very strong empirical evidence that they're wrong. I should have made the connection months ago, but I didn't until I saw it spelled out in these videos from the excellent YouTube channel Closer to Truth. I'm mostly just going to repeat what Sam Parnia, MD says in the videos. To recap what I've learned and mentioned before, so-called near-death experiences follow a common pattern across cultures, but they also have differences - most significantly, the identity of the heavenly being that one encounters depends on one's religious background. So they don't necessarily prove anything about the objective reality of the afterlife. Maybe they're a delusion hardwired into our brains and shaped by cultural influences, or maybe a higher power shows itself differently depending on what we're expecting and comfortable with. Also, they can be triggered by drugs or surgeries where one's life isn't actually in danger. But they're very elaborate and have powerful, positive long-term life-changing effects that delusions are not generally known to have. Someone in the comments section on another video suggested that they're an adaptation by the brain to give us a peaceful death if all attemps to keep us alive fail. But a peaceful death does zilch to improve our odds of passing our genes along, so such an adaptation could only have evolved by pure coincidence.

Anyway, Sam Parnia, MD spells out a fact that I should have grasped on my own. The term "near-death experience" is misleading because many of the people who have them are quite literally completely dead. Their hearts and brains have shut down. And for most of history, that would have always been the end of it. But technology has advanced to the point that they can sometimes be brought back to life minutes or even hours after their hearts and brains have shut down, before all their cells have also died. And then they report these near-death experiences. Which means that, regardless of what those experiences can or can't tell us about an afterlife, those people were still conscious while they were dead. I don't know why this isn't being shouted from every rooftop in the world. Before, I just thought maybe they still had some brain activity that we couldn't detect, but now I realize how implausible that is, especially since it would seem to render a lot of detectable brain activity superfluous. Now this doesn't prove that consciousness lasts forever after death, but if it can last at all without a functioning brain to contain it, I don't see why it would just fizzle out some time later. This is a very strong empirical basis for believing that we're eternal beings. I don't believe in the traditional view of "spirits" (and a lot of modern Christians don't either) because there's no evidence that a body needs a spirit inside it to be alive. Individual cells are alive, clumps of cells are alive, really big clumps of cells (like us) are alive, and there's no indication at any level that the organelles or organs are insufficient to maintain that state on their own. But I agree with the philosophical argument that brain cells and electricity can't produce consciousness on their own because there's a qualitative difference between those physical things and that ethereal, subjective thing. I'm very attracted to the view that consciousness permeates the universe and brains are like radio sets that pick it up. To me, this makes scientific and theological sense. I think our innermost core is consciousness, not spirit. And that actually reminds me of Joseph Smith's idea that we started out as intelligences that are co-eternal with God. I always liked that idea because it solved the problem of God being responsible for our imperfections and our sins. I don't believe he was a prophet by any stretch, but was very intelligent and he may have stumbled onto some correct ideas just by logic. I believe that we are eternal beings and that when we die, we'll be surprised to remember the things we knew before we were born. Now I can stop being afraid of death and look forward to it again. I think. I just want to reunite with loved ones and explore the universe, but I am still a little concerned about the possibility of reincarnation. I'd actually prefer the total annihilation of my consciousness to having another life on this hellhole planet without retaining anything I learned in this one. But reincarnation is supposed to suck, and the whole point of Hinduism is to get out of it. I'd better live a really good life just in case karma is an actual thing that exists. I've fallen behind on my commitment to post weekly because I didn't plan ahead, and this weekend I was occupied with a friend who traveled a bit of distance for my birthday and stayed for a couple of days. And then I was just really, really, tired, and I still am but I'm getting this post out of the way so I don't keep falling behind.

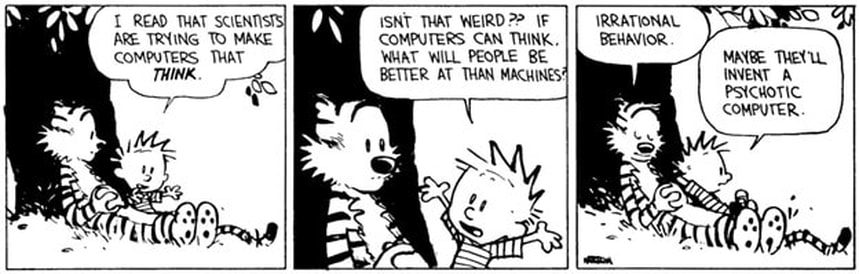

In part I'm tired because for weeks I haven't slept well even by my standards. I think I have a lot of anxiety and trauma building up that I don't consciously feel much, but that bubbles closer to the surface as I approach the threshold between consciousness and other stuff. One recent morning, after waking up hours earlier than I wanted to and failing to get back to sleep, I dreamed while still awake, as I do more often than normal people probably do. I was partially lucid. When I found myself high above the Earth, I quickly decided that I was just floating in orbit and wouldn't fall because falling is my biggest fear in the world. So I was floating in orbit, and then the view zoomed out to show more of the galaxy, and of course almost immediately I was invisible, and I - real life I, not dream I - almost burst into tears at how much I don't matter. So apparently that's an anxiety I have bottled up ever since I read Carl Sagan's book Cosmos. His books really mess me up, but he seems like such a decent guy, I can't get mad at him. Then, too, on Sunday night I went up Logan Canyon with this friend and a few other friends. We were going to camp up there, but we just did a campfire and ate stuff and drank stuff until almost 12:30 before we all chickened out and came home. I suffered a lot for making those memories, but I guess it was worth it because toward the end the moon vanished behind the mountain and we could see a backdrop of magic sparkly stuff behind the larger stars. Just to make conversation, I taught the others that it's called the Milky Way because it came out of the goddess Hera's breast. And just to make conversation, I asked the others if it made them feel insignificant. One friend said no, actually the opposite, because he feels like it was all made for him. I jokingly called him a narcissist. I thought of the love I felt for these friends and the camaraderie I was enjoying with them that night, and I thought what a shame it will be if that all vanishes forever when we die because our existence and our human connections are really just an insignificant and temporary accident. AI is making a lot of people feel insignificant too. If you're like me, you're really tired of hearing the word "ChatGPT" over and over and over again. A guy at the local Unitarian Universalist church gave a presentation on it on Sunday morning, talking about its positives and negatives and spiritual implications, and I finally saw it operating in real time as he made it rewrite the story of the three little pigs with the wolf converting to Unitarian Universalism, then rewriting it again in the style of Roald Dahl and then in the style of Shel Silverstein. And then he made it produce photorealistic images of Joe Biden as a karate master. Naturally, as one who hopes to someday make a living by writing, I'm a little concerned that AI will make my talents unnecessary and condemn me to the kind of menial factory job that robots should be doing. People say not to worry about it because AI isn't that good. Well, maybe it isn't yet, but it will improve. That's how technology works. Its current skill level would have been unfathomable five years ago, and its skill level five years from now is all but guaranteed to be exponentially greater. I tried out some AI stuff myself over the last couple days, and they were just free websites that wouldn't write very long stories, but still I was amazed at the coherence and detail that emerged from my prompts. AI is artificial intelligence. It's dependent on input from humans with human brains. It can't actually think. It isn't actually conscious. That's an illusion. But might it someday be real? Is it possible to create truly conscious machines? David Bentley Hart, is his philosophy book, says no. He points out that there's a huge difference between how computers work and how brains work, and metaphors about the brain as a computer really obfuscate that fact, and he claims that brains are too complex and that subjective consciousness can't be replicated just by replicating their physical processes because there's an insuperable qualitative difference between those things. Indeed, I just read in the news that a neuroscientist lost a 25-year bet with a philosopher about whether by this year scientists would have figured out how neurons produce consciousness. They haven't. But if somehow they ever do, and then AI replicates it, we're all screwed in a lot of ways. Fittingly, this was today's GoComics Calvin and Hobbes rerun. In The Experience of God: Being, Consciousness, Bliss, David Bentley Hart argues that there's an insuperable quantitative gap between the the physical material of the human brain and the subjective personal experience of consciousness; in other words, one cannot produce the other on its own. This isn't a "God of the gaps" argument. It's not about what materialism can't explain yet but about an intrinsic limitation of materialism. He insists that no matter how much we learn about someone's brain structure and activity, we will never be able to replicate for ourselves what it's like to be them. He goes into a lot more depth with this argument than I can. He also rejects, for good reason, the scientifically unsupported belief that bodies require spirits inside of them in order to be alive at all. If I understand and remember correctly, he asserts that consciousness flows from God in the same way that existence itself flows from God.

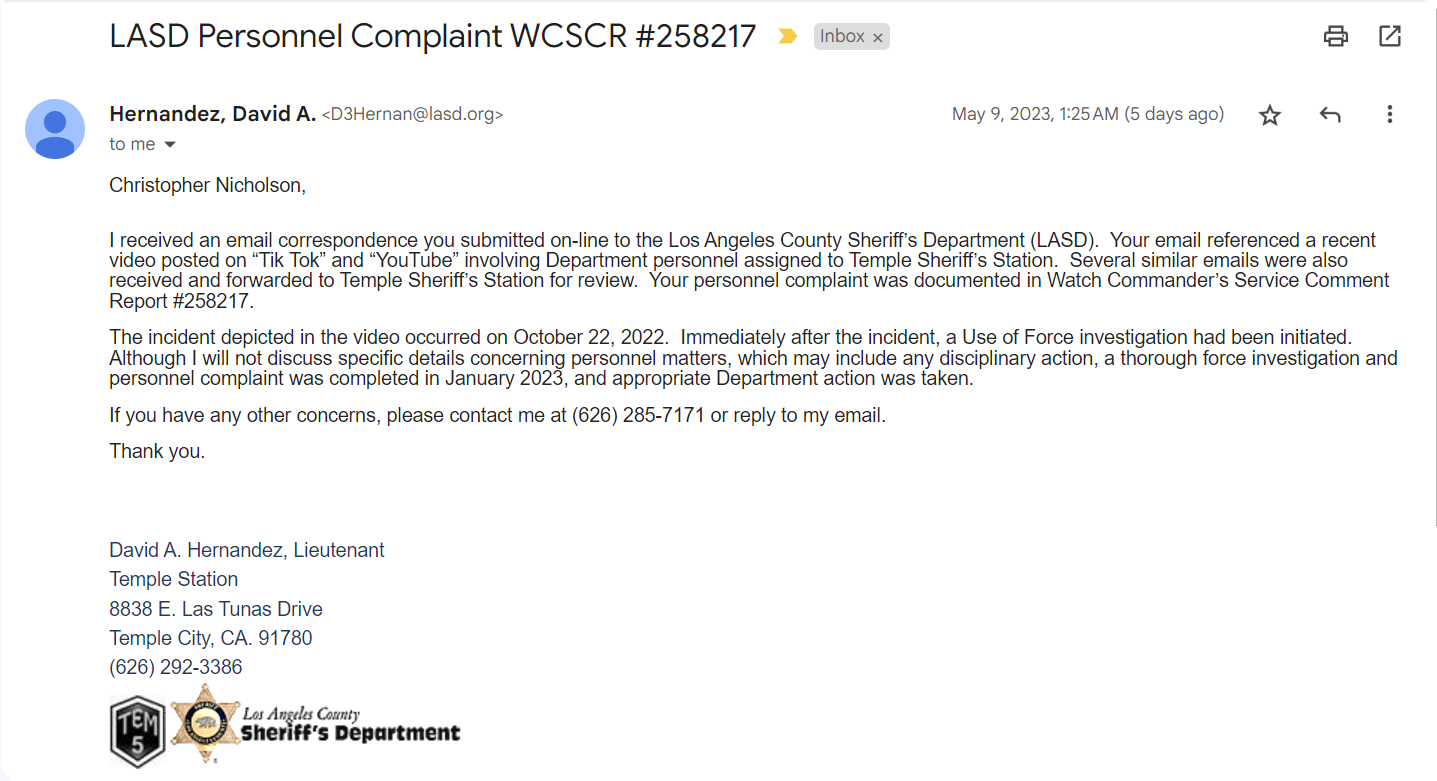

Writing in Psychology Today this week, in an article that was recommended to me by the almighty algorithms because I read some articles on that website about near-death experiences, Steve Taylor makes a similar argument and includes an analogy that blew my mind: "It may be that the human brain does not actually produce consciousness but transmits it. Like a radio, the brain may 'pick up' fundamental consciousness from the space around us and transmit it to us, so that we become individually conscious." To me this makes perfect sense in principle. It explains why the brain's machinery is necessary in the first place, and even why its makeup strongly influences our thoughts and feelings, despite not being the ultimate source of consciousness. And it's so simple. You don't need a book of philosophy to understand it. It does raise further questions, though. As Taylor points out, the materialist view "also means that there cannot be an afterlife, since human consciousness cannot outlive the brain that produces it" (although I heard a Christian pastor who doesn't believe in the body/spirit dualism explain that God could recreate our personalities and identities in the resurrection exactly as they were, and argue with a skeptic about whether these new people would really still be us). But if the brain just receives and interprets a piece of a big mass of consciousness, do we just get absorbed back into that when we die? I guess becoming part of God, or one with the Force or whatever, would be nice, but I also like being me and don't want to give that up altogether. And if we all become unified into one consciousness at the end, then any love we have for each other ultimately becomes love for ourself, and that just seems a lot less special. Taylor raises another interesting point: "Until the 19th century, almost every culture in human history took for granted that the essence of human identity was non-physical and would survive the death of the body." It's interesting because it may or may mean anything. It's entirely possible for almost every culture in human history to be wrong about something, and maybe this kind of belief is just coping mechanism for the horrors of mortality. But maybe it's an instinctive understanding that most of us have because it's true and our consciousnesses have advanced far enough to grasp it. David Bentley Hart talks about how we know or at least have reasonable grounds to assume many things that we can't prove scientifically - mathematics, for example. This could be one of those things. It's a real shame that the only way to confirm it for sure is to die. Tomorrow is Juneteenth. Last year when it became a federal holiday I witnessed a lot of complaining from Utah Republicans who are determined to be horrible people and wrong about everything, but I haven't seen any yet this year. I guess they grew the hell up and got over it. Now if only they could do the same for everything else. We also just had Summerfest, the local arts festival here in Logan, over the last three days. I always go and don't buy any art because it's expensive but then I rationalize buying the expensive food because it's part of the experience. I went alone the first two days and then I went with a friend the last day, and she didn't buy much, but she talked to several of the booth owners and took their business cards, which I guess is the equivalent of clicking "like" on a Facebook fundraiser instead of donating to it. Then last night, because I'm still on the email list for the Mormon Environmental Stewardship Alliance, I attended a screening of "Stewart Udall and the Politics of Beauty" over Zoom. He was a phenomenal guy and the world needs more like him right now to tackle its environmental and social problems. It's funny, though, how Mormonism still claims him and takes credit for his accomplishments even though he stopped practicing it in his twenties, in large part because it was so socially backwards even by 1947 standards. Because I read about near-death experiences recently, of course the omniscient internet brought to my attention the most recent development in that field. Four people hooked up to life support were having their brains monitored for whatever reason, and after they were taken off life support, two of their brains registered a surge of activity in the part responsible for dreams. Scientists speculate that these people were having NDEs, although they had a history of epilepsy, and nobody's ever shown a correlation between epilepsy and NDEs. The headline I looked at claimed that scientists had observed the brain activity behind NDEs for the first time, as if that were an established fact, but of course it isn't. They don't know what they actually observed. In order to know that, or at least be fairly confident, they'd have to observe something similar in the brain of someone who subsequently came back to life and reported on it. Science may sooner or later explain NDEs away as a purely neurological phenomenon, but it hasn't yet and we mustn't be premature about it. Journalists often take the nuance out of science, either out of sincere ignorance or the need to produce clickbait. My roommate has finally moved out. He moved upstairs, meaning that he wanted to stay in this complex but not with me. The feeling is mutual. I didn't like that he left lights on he wasn't using (though I trained him by example to not do it constantly), I didn't like that he walked around without a shirt on when the weather was warm, I didn't like that he spent two hours a day in the bathroom, and I especially didn't like that he spent at least an hour a day practicing what can only be called "singing" under the most generous interpretation at the top of his lungs. It sounds more like an air raid siren. I had a friend over once and he laughed in disbelief at how bad it was. I sent a recording to another friend whom my complaints had made curious, and she wrote back, "PUT IT OUT OF ITS MISERY. WTF." Early on, at a public gathering, my roommate put me on the spot and asked if his singing annoyed me. Trying to balance tact with honesty, I said, "Only when it's really loud" (which was always). So he continued to consistently do it at the top of his lungs. Now I feel bad that I've been festering in resentment instead of asking him to stop, though, because I warned my upstairs neighbor about it, and I shouldn't have been surprised to learn that he hasn't been enjoying it either. Recently the Temple City Sheriff's office invaded the wrong home without a warrant and illegally questioned and arrested two children who now, presumably, are traumatized for life but at least won't grow up to be bootlickers. I wrote some strong language in an online form somewhere and fully expected, based on previous interactions with law enforcement, that they would ignore me, but that the publicity would make them think twice (or at least once) about pulling such stunts in the future. I was quite surprised when someone got back to me earlier this week. Credit where it's due. I've started wasting time on Twitter instead of reddit lately. I used to do essentially nothing on Twitter except share my blog posts, and I stayed at 38 followers for over six years. Now after a few weeks of interacting with people, I'm up to 53, so yay. Twitter brings out the worst in people, including me, because it has almost no rules. Before Elon Musk took over, my account was suspended for wishing death on (checks notes) Vladimir Putin. And I still do and I'm not sorry. But now, I can say whatever the hell I want without fear of consequences. I've had some arguments. Even though I only follow ex-Mormons and liberal Mormons as far as Mormon stuff is concerned, I keep getting conservative Mormons in my feed, and they're pretty much the worst people in the world. Half their identity right now revolves around hating transgender people, and the other half is divided between hating apostates, hating liberals, hating scholars, hating gay people, and hating feminists. They're straight-up bullies more often than not, and because they think they're boldly standing up for truth and righteousness, they're quite incapable of attaining any self-awareness about how awful they are. Case in point: I mean, wow. I used to have a hell of a persecution complex myself, but I don't think there was ever a point when I would have told someone "You are a demonic force and will be treated accordingly." It frightens me that people who think that way exist. Of course, guys like this think I'm a demonic force too. I try to be good. I don't set out to tear down Mormon beliefs every time I see them in my feed. I only get involved if they say something egregiously stupid and/or bigoted. And I try not to mock or insult them until they do it to me first, but that usually doesn't take very long. Personal attacks are usually their first and only response to critique of any kind. They really thought they were clever for pointing out that I had my pronouns in my bio and a Ukrainian flag next to my name. I had to block an account with the word "Christ" in its name that insisted Ukraine "isn't innocent" and basically deserves what it's getting, a claim that could be made with a little more accuracy (though it would still be victim-blaming) about the Mormons who moved into Missouri and boasted that the Lord would give them their neighbors' land. I added a Pride flag and a transgender flag to my Ukrainian flag just to bother these troglodytes, and then I added "If my flags and pronouns bother you, mission accomplished" to my bio to make sure they know that I'm bothering them on purpose, and now they don't bring that stuff up as much.

The leaders of the church don't appear to care that in a few years, people like this will be the only members they have left. Decent, intelligent, empathetic people are being alienated in droves. Of course, some of these jackasses also get alienated every time the church takes a position against bigotry or in favor of modern medicine - the other day one even confessed that he struggles with his faith and desire to attend church because a Primary teacher elsewhere on Twitter wore a rainbow pin - but overall, I think they're winning. Perhaps in fifty years, this church will make the Westboro Baptist Church look like a happy memory. Perhaps it will truly be The Church of Brigham Young, Ezra Taft Benson, and Donald J. Trump. (One of the guys I argued with had modeled his profile after Spencer W. Kimball, though. Kimball's a more nuanced figure in my book. If I meet him in the next life, I'll thank him for what he did to advance racial equality within the church, then kick him between the legs for the vile things he said about women and gay men.) |

"Guys. Chris's blog is the stuff of legends. If you’re ever looking for a good read, check this out!"

- Amelia Whitlock "I don't know how well you know Christopher Randall Nicholson, but... he's trolling. You should read his blog. It's delightful." - David Young About the AuthorC. Randall Nicholson is a white cisgender Christian male, so you can hate him without guilt, but he's also autistic and asexual, so you can't, unless you're an anti-vaxxer, in which case the feeling is mutual. This blog is where he periodically rants about life, the universe, and/or everything. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

- Home

- Blog

-

My Literary Works

- Comics by C. Randall Nicholson >

-

Short Stories by C. Randall Nicholson

>

- Childish Stories

- My Dearest Catherine

- It's Really Cold Out There

- Walter Mitty - The Sixth Daydream

- Jesus is a Liberal

- El Coronel - Epílogo

- A Couple of Very Cynical Parables

- Interview with the Ruler of the World (Me)

- The Star Wars Missionary

- Chelise

- Traumfrau

- All Hands on Deck

- It Ain't Ogre Till It's Ogre

- Black Tom: The Unauthorized Encore

- Brittany and the Bear

- Lunatics: A Space Girls Story

- Adventures in the FDR >

- Poems and Songs by C. Randall Nicholson >

-

Essays by C. Randall Nicholson

>

- Childish Essays by C. Randall Nicholson

- Los Braceros

- The Great Pacific Garbage Patch

- The Witches of "Macbeth"

- Evita

- The Second Amendment to the Constitution: Why it is Important to Our Nation

- USU Honors Program Application Essay

- The Giraffe Deception

- Member Missionary Message

- I'm Just a Little Unwell: Coping with Asperger's Syndrome

- Dating Seminar

- An Open Letter to Critics of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

- How Can any Intelligent Person Be a Mormon?

- Faith and Doubt in My Life

- Discarding Dated Dinosaur Dogmas: Robert T. Bakker and the Dinosaur Renaissance

- Religion, Science, and Art: Elements of the Gospel of Truth

- Why Latter-day Saints Should Embrace Evolution

- Daoism

- Spiritual Autobiography

- From the East: Hinduism and Islam as Compared to My Western Faith Tradition through Poetry

- In Defense of Pickup Lines

- Ass Burgers

- Chasing Kelsey

- Both of the Things Wrong with Charlotte Temple

- Sir Thomas More's Critiques and Commendations for Catholicism

- The Legend of Christor

- How Eugene England Helped Me Transform My Testimony

- Graduate School Statement of Intent

- "Please Join with Us Now in Common Purpose": A Discourse Analysis

- Legos and Gender

- Things That Rhyme with "Elise"

- I Want to Believe: The Persistence of Alien Folklore

-

Reviews by C. Randall Nicholson

>

- Review of "Howard the Duck"

- Review of "Letter to a Christian Nation"

- Review of the LDS Institute's "Uncommon Hour"

- Review of "Madagascar 3"

- Review of "Dating Doctor David Coleman"

- Review of "David and the Magic Pearl"

- Review of the "Mata Nui Online Game (MNOG)"

- Review of "Evolution and Mormonism"

- Review of "Callahan's Crosstime Saloon" (Game)

- Review of "Modern Romance"

- Review of "Solo: A Star Wars Story"

- Review of "The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time"

- Review of "The Book of Mormon" (Musical)

- Review of Jenson Books

- Review of "Live Not By Lies"

-

Literary Fragments by C. Randall Nicholson

>

- Childish Scraps

- The Adventures of Nichch Bror

- Reaching (for the Stars)

- Boys vs. Girls Book 1: The Conflict >

- Dave is a Square

- Star Wreck

-

The Legend of Aaron LaBarr

>

- 1 Marauders of the Mythical Man Chapter One

- 1 Marauders of the Mythical Man Chapter Two

- 1 Marauders of the Mythical Man Chapter Three (Unfinished)

- 1 Marauders of the Mythical Man Chapter Four (Unfinished)

- 2 Crusaders of the Crystalline Chronostone Chapter One (Unfinished)

- 2 Crusaders of the Crystalline Chronostone Chapter Two (Unfinished)

- 2 Crusaders of the Crystalline Chronostone Chapter Three (Unfinished)

- 2 Crusaders of the Crystalline Chronostone Miscellaneous

- 3 Pursuers of the Priceless Power Chapter Two (Unfinished)

- The War >

- The Space Detective

- Skin Deep

- The Sword of Laban >

- LDS Church History Timeline

- Jennifer and Lance

- Logan YSA 36th Ward 2018 History

- Unsent Correspondence by C. Randall Nicholson

- Correspondence Regarding the Worst Day of My Life So Far

-

Indiana Jones and the Saucer Men from Mars

>

- Indiana Jones and the Saucer Men from Mars - Prologue

- Indiana Jones and the Saucer Men from Mars - Chapter One

- Indiana Jones and the Saucer Men from Mars - Chapter Two

- Indiana Jones and the Saucer Men from Mars - Chapter Three

- Indiana Jones and the Saucer Men from Mars - Chapter Four

- Indiana Jones and the Saucer Men from Mars - Chapter Five

- Indiana Jones and the Saucer Men from Mars - Chapter Six

- Indiana Jones and the Saucer Men from Mars - Chapter Seven

- Indiana Jones and the Saucer Men from Mars - Chapter Eight

- Indiana Jones and the Saucer Men from Mars - Chapter Nine

- Indiana Jones and the Saucer Men from Mars - Chapter Ten

- Indiana Jones and the Saucer Men from Mars - Chapter Eleven

- Indiana Jones and the Saucer Men from Mars - Chapter Twelve

- Indiana Jones and the Saucer Men from Mars - Chapter Thirteen

- Indiana Jones and the Saucer Men from Mars - Epilogue

- Behind the Scenes of "Indiana Jones and the Saucer Men from Mars"

-

Indiana Jones and the Monkey King

>

- Indiana Jones and the Monkey King - Prologue

- Indiana Jones and the Monkey King - Chapter One

- Indiana Jones and the Monkey King - Chapter Two

- Indiana Jones and the Monkey King - Chapter Three

- Indiana Jones and the Monkey King - Chapter Four

- Indiana Jones and the Monkey King - Chapter Five

- Indiana Jones and the Monkey King - Chapter Six

- Indiana Jones and the Monkey King - Chapter Seven

- Indiana Jones and the Monkey King - Chapter Eight

- Indiana Jones and the Monkey King - Chapter Nine

- Indiana Jones and the Monkey King - Chapter Ten

- Indiana Jones and the Monkey King - Chapter Eleven

- Indiana Jones and the Monkey King - Chapter Twelve

- Indiana Jones and the Monkey King - Chapter Thirteen

- Indiana Jones and the Monkey King - Chapter Fourteen

- Indiana Jones and the Monkey King - Epilogue

- Running Logan Canyon

- Crusaders of the Chrono-Crystal >

-

About Me

-

About Mormons

- Why Are Mormons So Hot?

- LDS Temples

-

LDS Scriptures

>

- Growth of the LDS Church

-

LDS Racial History

>

- The Lamanite Curse in the Book of Mormon

- The LDS Church and Native Americans Nineteenth Century

- The LDS Church and Native Americans Twentieth Century

- The LDS Church and Native Americans Twenty-first Century

- Black Latter-day Saints Before June 1978

- Abner Howell, Black Latter-day Saint

- Dr. Lowry Nelson vs. the LDS First Presidency

- Race Problems - As They Affect the Church

- Ezra Taft Benson vs. the Civil Rights Movement

- The LDS Church and Slavery

- The LDS Church and Interracial Marriage

- The LDS Church and Black People: Historical Context (Pre-1830)

- The LDS Church and Black People 1830-1837

- The LDS Church and Black People 1838-1842

- The LDS Church and Black People 1843-1844

- The LDS Church and Black People 1845-1848

- The LDS Church and Black People 1849-1852

- The LDS Church and Black People 1853-1860

- The LDS Church and Black People 1861-1868

- The LDS Church and Black People 1869-1878

- The LDS Church and Black People 1879-1889

- The LDS Church and Black People 1890-1899

- The LDS Church and Black People 1900-1903

- The LDS Church and Black People 1904-1907

- The LDS Church and Black People 1908-1912

- The LDS Church and Black People 1913-1930

- The LDS Church and Black People 1931-1946

- The LDS Church and Black People 1947

- The LDS Church and Black People 1948-1954

- The LDS Church and Black People 1955-1959

- The LDS Church and Black People 1960

- The LDS Church and Black People 1961-1962

- The LDS Church and Black People 1963

- The LDS Church and Black People 1964

- The LDS Church and Black People 1965

- The LDS Church and Black People 1966

- The LDS Church and Black People 1967

- The LDS Church and Black People 1968

- The LDS Church and Black People 1969

- The LDS Church and Black People 1970

- The LDS Church and Black People 1971-1972

- The LDS Church and Black People 1973-1975

- The LDS Church and Black People 1976-1977

- The LDS Church and Black People 1978

- The LDS Church and Black People 1979-1984

- The LDS Church and Black People 1985-1988

- The LDS Church and Black People 1989-1994

- The LDS Church and Black People 1995-1998

- The LDS Church and Black People 1999-2002

- The LDS Church and Black People 2003-2006

- The LDS Church and Black People 2007-2010

- The LDS Church and Black People 2011-2012

- The LDS Church and Black People 2013-2015

- The LDS Church and Black People 2016-2017

- The LDS Church and Black People 2018

- The LDS Church and Black People 2019

- The LDS Church and Black People 2020

- The LDS Church and Black People 2021

- The LDS Church and Black People: Moving Forward

- The Bruce R. McConkie Fan Page

- LDS Culture Pet Peeves

- Why I Wholeheartedly Accept Organic Evolution >

- Are the General Authorities Human?

- A Brief History of LDS Polygamy

- A Brief History of Women in the LDS Church >

- Is the LDS Church Homophobic? >

- The LDS Church and Islam / كنيسة يسوع المسيح والإسلام

- Heavenly Mother

- Mormons in America

- The Tragedy of Kip Eliason

- Is the Book of Mormon a Fraud

- Joseph Smith's Prophecies >

- Mormonism's Infallible Prophets

- A Response to the Address "The Real Meaning of the Atonement"

- Affection in Marriage

- Is There No Help for the Widow's Son?

-

An Address to All Believers in Christ

>

- An Address to All Believers in Christ - Chapter I

- An Address to All Believers in Christ - Chapter II

- An Address to All Believers in Christ - Chapter III

- An Address to All Believers in Christ - Chapter IV

- An Address to All Believers in Christ - Chapter V

- An Address to All Believers in Christ - Chapter VI

- An Address to All Believers in Christ - Chapter VII

- An Address to All Believers in Christ - Chapter VIII

- An Address to All Believers in Christ - Chapter IX

- An Address to All Believers in Christ - Chapter X

- An Address to All Believers in Christ - Chapter XI

- An Address to All Believers in Christ - Chapter XII

-

These Amazing Mormons!

>

- Introduction

- I. Meeting the Mormons

- II. Holy Books

- III. The Capital of Mormondom

- IV. Industrial Adaptation

- V. Church Organization

- VI. The Priesthood

- VII. Relief Society

- VIII. Church Welfare Program

- IX. The Word of Wisdom

- X. Business, Labor, Politics

- XI. Architecture

- XII. Education

- XIII. Their Missionary System

- XIV. Propaganda

- XV. The Family

- XVI. Sunday School

- XVII. Primary

- XVIII. Young People

- XIX. The Temple

- XX. Polygamy

- About the Author

- Anti-Mormonism >

- Why I Left the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

-

Whatever

- The Milo Nicholson Memorial Page

- My Unsolicited Spiel on Abortion

- Anti-Vaxxers Make Me Sick

- In Defense of Pedophiles

- The Kyle Cootware Memorial Page

- My Artistic Creations

- Women >

- How to Make a Movie

- The Progressive Bill of "Rights"

- Back in the USSR

- Why We Should Support the War on Drugs

- Why I Love India

- The Joys of DOSBox

- The Hugh Hefner Memorial Page

- Why Engagement Rings are Stupid

- Creating a Pedagogy of Critical Thinking and Student Agency

- Karzahni

- Contact

- Links

crandallnicholson at gmail dot com

My other websites:

Amazon Author Page

Life, the Universe, and Everything Wiki

Entebbe Alpha & Omega Development Organization Uganda

Everything that can be copyrighted by me is © C. Randall Nicholson (he/him) 2010-2024, and everything that cannot is not. As should be obvious to any reasonable person, this website is not owned by, endorsed by, sponsored by, accepting bribes from, or affiliated in any way with The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Utah State University, any political parties or candidates, Lucasfilm, Nintendo, the Irish Mafia, or anyone else except me. The inclusion of external sources is not an endorsement of every viewpoint or claim contained therein. Due to government restrictions, this website is not available in Abbudin, Agrabah, Aidnaryk, Aldastan, Aldovia, Aleshar, Algaria, Alphenlicht, Andalasia, Ankh-Morpork, Arcium, Arendelle, Arendia, Arjuna, Armaeth, Artakha, Artidax, Astel, Atan, Attolia, Avalon, Beltrazo, Benlucca, Berzerkistan, Bialya, Blefuscu, Borduria, Borogravia, Brovania, Brynnel, Bulungi, Calatia, Caldonia, Cammoria, Carbombya, Carnolitz, Casbahmopolis, Catan, Cherek, Chima, Chyrellos, Cthol Murgos, Cynesga, Cythera, Daconia, Dacovia, Däfos, Dalasia, Dalsona, Daxia, Deira, Delchin, Deltora, Derka-derkastan, Destral, Dinotopia, Drasnia, Duban, Dubatio, Eddis, Edom, Eire, Elbonia, Elenia, Enchancia, Equatorial Kundu, Equestria, Erewhon, Flatland, Florin, France, Freedonia, Fuh, Gamelon, Ganesia, Gar og Nadrak, Genosha, Genovia, Gilead, Goona, Gorch, Grand Fenwick, Guilder, Gwyliath, Haganistan, Holodrum, Honalee, Hortensia, Hyrule, Hytopia, Illyria, Ishtar, Jedera, Jemal, Jenno, Jiardasia, Jueland, Kadir, Kalynthia, Kamistan, Kantaria, Katakor, Katurrah, Kazhistan, Khairpura-Bhandanna, Khakistan, Khemed, Kibalakaboo, Koholint, Kookatumdee, Koridai, Krakozhia, Kumranistan, Kunami, Kyrat, Kyrzbekistan, Labrynna, Lamorkand, Latveria, Lemmink, Lichtenslava, Lilliput, Lorule, Lotharia, Lubovosk, Maldonia, Maragor, Mata Nui, Matar, Medici, Mesociam, Metru Nui, Mishrak ac Thull, Moldera, Monterria, Muldavia, Nambutu, Narnia, Naruba, Nehwon, North Azbaristan, Nuevo-Rico, Nutopia, Nyissa, Nynrah, Odina, Okoto, Oriana, Oz, Pallia, Panem, Pappyland, Patusan, Pelosia, Penglia, Perivor, Pilchardania, Pincoya, Pingo-Pongo, Poldavia, Poptropica, Pottsylvania, Quelf, Qumar, Qumran, Qurac, Ramat, Rendor, Riva, Ronguay, Ruritania, Samavia, San Lorenzo, San Theodoros, São Madrigal, São Rico, Scatland, Schmuldavia, Sendaria, Shamar, Slafka, Slokovia, Slorenia, Sodor, Sokovia, Sondonesia, Sosaria, Sounis, South Azbaristan, Stelt, Strong Badia, Subrosia, Syldavia, Sylvania, Tamul, Tanol, Tarenta, Tashistan, Tega, Terabithia, Termina, Tetaragua, Thalesia, Thatotherstan, Thulahn, Tolemac, Tolnedra, Tomania, Transia, Trazere, Turaqistan, Turmezistan, Ul'dah, Ulgoland, the United States of Auradon, Utopia, Valesia, Velattiane, Voresbo, Voya Nui, Wadata, Wadiya, Wakanda, Westeros, Wongo, Wrenly, Xanth, Xia, Zakaz, Zamad, Zamunda, Zaraq, Zekistan, or Zenovia. I apologize for the inconvenience.

My other websites:

Amazon Author Page

Life, the Universe, and Everything Wiki

Entebbe Alpha & Omega Development Organization Uganda

Everything that can be copyrighted by me is © C. Randall Nicholson (he/him) 2010-2024, and everything that cannot is not. As should be obvious to any reasonable person, this website is not owned by, endorsed by, sponsored by, accepting bribes from, or affiliated in any way with The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Utah State University, any political parties or candidates, Lucasfilm, Nintendo, the Irish Mafia, or anyone else except me. The inclusion of external sources is not an endorsement of every viewpoint or claim contained therein. Due to government restrictions, this website is not available in Abbudin, Agrabah, Aidnaryk, Aldastan, Aldovia, Aleshar, Algaria, Alphenlicht, Andalasia, Ankh-Morpork, Arcium, Arendelle, Arendia, Arjuna, Armaeth, Artakha, Artidax, Astel, Atan, Attolia, Avalon, Beltrazo, Benlucca, Berzerkistan, Bialya, Blefuscu, Borduria, Borogravia, Brovania, Brynnel, Bulungi, Calatia, Caldonia, Cammoria, Carbombya, Carnolitz, Casbahmopolis, Catan, Cherek, Chima, Chyrellos, Cthol Murgos, Cynesga, Cythera, Daconia, Dacovia, Däfos, Dalasia, Dalsona, Daxia, Deira, Delchin, Deltora, Derka-derkastan, Destral, Dinotopia, Drasnia, Duban, Dubatio, Eddis, Edom, Eire, Elbonia, Elenia, Enchancia, Equatorial Kundu, Equestria, Erewhon, Flatland, Florin, France, Freedonia, Fuh, Gamelon, Ganesia, Gar og Nadrak, Genosha, Genovia, Gilead, Goona, Gorch, Grand Fenwick, Guilder, Gwyliath, Haganistan, Holodrum, Honalee, Hortensia, Hyrule, Hytopia, Illyria, Ishtar, Jedera, Jemal, Jenno, Jiardasia, Jueland, Kadir, Kalynthia, Kamistan, Kantaria, Katakor, Katurrah, Kazhistan, Khairpura-Bhandanna, Khakistan, Khemed, Kibalakaboo, Koholint, Kookatumdee, Koridai, Krakozhia, Kumranistan, Kunami, Kyrat, Kyrzbekistan, Labrynna, Lamorkand, Latveria, Lemmink, Lichtenslava, Lilliput, Lorule, Lotharia, Lubovosk, Maldonia, Maragor, Mata Nui, Matar, Medici, Mesociam, Metru Nui, Mishrak ac Thull, Moldera, Monterria, Muldavia, Nambutu, Narnia, Naruba, Nehwon, North Azbaristan, Nuevo-Rico, Nutopia, Nyissa, Nynrah, Odina, Okoto, Oriana, Oz, Pallia, Panem, Pappyland, Patusan, Pelosia, Penglia, Perivor, Pilchardania, Pincoya, Pingo-Pongo, Poldavia, Poptropica, Pottsylvania, Quelf, Qumar, Qumran, Qurac, Ramat, Rendor, Riva, Ronguay, Ruritania, Samavia, San Lorenzo, San Theodoros, São Madrigal, São Rico, Scatland, Schmuldavia, Sendaria, Shamar, Slafka, Slokovia, Slorenia, Sodor, Sokovia, Sondonesia, Sosaria, Sounis, South Azbaristan, Stelt, Strong Badia, Subrosia, Syldavia, Sylvania, Tamul, Tanol, Tarenta, Tashistan, Tega, Terabithia, Termina, Tetaragua, Thalesia, Thatotherstan, Thulahn, Tolemac, Tolnedra, Tomania, Transia, Trazere, Turaqistan, Turmezistan, Ul'dah, Ulgoland, the United States of Auradon, Utopia, Valesia, Velattiane, Voresbo, Voya Nui, Wadata, Wadiya, Wakanda, Westeros, Wongo, Wrenly, Xanth, Xia, Zakaz, Zamad, Zamunda, Zaraq, Zekistan, or Zenovia. I apologize for the inconvenience.

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed