Why I Left the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS/Mormon)

May 2022

I don't have the usual male apostate's checklist of qualifications. I didn't graduate seminary, I didn't serve a mission, I was never Elders Quorum president, I didn't marry in (or out of) the temple. But I was fiercely committed to The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints as a teenager and for my first decade of adulthood. I wanted to be a beacon leading souls to Christ, a role model for balancing faith and reason, someone that people could look to and say "He's intelligent and knows about all the issues and still believes, so I can too." Perhaps I felt a bit prideful about staying in the church while leaving it was the trendy, obvious choice for my generation. Changing my mind was very hard, embarrassing, and long overdue.

Terryl Givens says that faith is a choice laden with moral significance, and depending on the choice, one can marshal arguments and evidence for or against it. Despite my doubts and questions, for years I consciously chose faith in this specific religion out of fidelity to my spiritual experiences (most of which I still believe were legitimate) and to the scriptures and aspects of the theology that I "knew" were true (some of which I still believe). However, the more I learned or experienced that didn't fit the orthodox church narrative, the more I had to qualify or nuance my testimony until it became all but meaningless, and I realized it was no longer honest (if it ever had been) to approach everything from the predetermined conclusion that the church is true. I'm not saying it has no truth or that it didn't teach me good values. But I no longer believe that the church is the Lord's "only true and living church" or that its leaders are "prophets, seers and revelators" in any meaningful sense, and although it does much good in the world, it also does much harm, including to some people very close to me, that I cannot tacitly approve by continuing to participate. My detailed reasons are as follows:

Terryl Givens says that faith is a choice laden with moral significance, and depending on the choice, one can marshal arguments and evidence for or against it. Despite my doubts and questions, for years I consciously chose faith in this specific religion out of fidelity to my spiritual experiences (most of which I still believe were legitimate) and to the scriptures and aspects of the theology that I "knew" were true (some of which I still believe). However, the more I learned or experienced that didn't fit the orthodox church narrative, the more I had to qualify or nuance my testimony until it became all but meaningless, and I realized it was no longer honest (if it ever had been) to approach everything from the predetermined conclusion that the church is true. I'm not saying it has no truth or that it didn't teach me good values. But I no longer believe that the church is the Lord's "only true and living church" or that its leaders are "prophets, seers and revelators" in any meaningful sense, and although it does much good in the world, it also does much harm, including to some people very close to me, that I cannot tacitly approve by continuing to participate. My detailed reasons are as follows:

Its Systemic Lack of Transparency

In August 2010, age seventeen, I stumbled upon my first "anti-Mormon" website and discovered a bunch of the things people typically cite for their loss of faith - Joseph Smith's 1826 trial, Joseph Smith's evolving accounts of the First Vision, Joseph Smith's failed prophecies, DNA evidence contradicting the Book of Mormon, the Book of Abraham not matching the papyrus, and so on. I was blindsided and confused, but because of my recent spiritual experiences at EFY (now FSY) I held onto my faith until I found answers. Most of the answers from FAIR and other apologists were good enough for me. What I could never resolve, though, was the feeling of betrayal at having to learn these things from hostile sources instead of the church itself, or why it had sanitized, dumbed down, and misrepresented its history, which is ethically dubious at best and has caused a lot of avoidable problems. Subsequent transparency initiatives like the Gospel Topics essays and the Saints history volumes were, by the admission of church historians Marlin K. Jensen and Steven E. Snow, a direct response to many faith crises like mine that were instigated by the internet. Why didn't prophets, seers and revelators have the foresight to be more honest before the internet gave them no choice? And it's even worse than mere inaction. Leonard J. Arrington and his staff tried to publish transparent history in the 1970s, but leaders like apostles Mark E. Petersen, Ezra Taft Benson, and Boyd K. Packer fought them at every turn. Apologists for the church compound the problem with their constant victim-blaming and dishonest attempts to pretend the church has been transparent all along. "I've known about these controversial things my whole life," they say. "If you didn't, it's your own fault for not using your free time to read everything the church has ever published. Look, the Ensign devoted an entire sentence to Joseph Smith's seer stone the year before you were born."

Since 1830, many teachings in the church have quietly disappeared, a few have been explicitly repudiated, and most have evolved to some extent. The changes themselves are not altogether unreasonable for a religion that believes in continuing revelation "line upon line, precept upon precept, here a little and there a little." Yet far more often than leaders and members appeal to this theological scaffolding, they assert or imply that the church is true because its teachings don't change. When changes are pointed out, members try really hard to downplay their significance. This is often done through the useless circular logic that "doctrine doesn't change." Everything taught within the church at a given time is "doctrine" for most intents and purposes - as the dictionary definitions of the word would suggest - until it changes, at which point it was obviously never doctrine because doctrine doesn't change. Related to this is the supposed dichotomy between unchangeable doctrines and changeable policies. Of course there is a legitimate difference between teachings and practices, and the church is by necessity far more transparent about the latter, but they are intertwined more often than not and may both change at the same time. Lumping everything that's changed under the category of "policy" just because it changed is more useless circular logic.

I had more success rationalizing the church's lack of financial transparency, but it fits into this general trend and illustrates the scope of the problem. The church used to share itemized financial reports in General Conference but stopped in 1960 in order to conceal the $8 million deficit created by Henry D. Moyle's overenthusiastic chapel-building program (which grew to a $32 million deficit by 1962). Apologists point out the obvious fact that it isn't required by American law to disclose its finances. I don't think that not being legally required to do something is a good enough reason for not doing it, and I think tithepayers deserve a clearer picture of where their money is going. Still, I faithfully paid tithing for most of my adult life despite never noticing the promised blessings. (Once, the very evening of the day that I paid tithing, I developed a toothache that ended up costing me well over a thousand dollars because I live in the United States, and two days after I paid tithing, my laptop's hard drive failed and cost me six hundred more.) In December 2019 a whistleblower exposed the church's $100 billion Ensign Peak "rainy day" fund. I don't know if the church actually violated any tax laws as he alleged, or whether Jesus would want it to spend more money on humanitarian aid and less on real estate development, but at a minimum I am annoyed that it tried to keep this fund a secret. Roger Clarke, the head of Ensign Peak, admitted that the church was afraid members would stop paying tithing if they knew how much money it had. That's pretty sketchy in my book. I stopped paying tithing a few months before I stopped believing altogether (and didn't notice any subsequent loss of blessings).

Since 1830, many teachings in the church have quietly disappeared, a few have been explicitly repudiated, and most have evolved to some extent. The changes themselves are not altogether unreasonable for a religion that believes in continuing revelation "line upon line, precept upon precept, here a little and there a little." Yet far more often than leaders and members appeal to this theological scaffolding, they assert or imply that the church is true because its teachings don't change. When changes are pointed out, members try really hard to downplay their significance. This is often done through the useless circular logic that "doctrine doesn't change." Everything taught within the church at a given time is "doctrine" for most intents and purposes - as the dictionary definitions of the word would suggest - until it changes, at which point it was obviously never doctrine because doctrine doesn't change. Related to this is the supposed dichotomy between unchangeable doctrines and changeable policies. Of course there is a legitimate difference between teachings and practices, and the church is by necessity far more transparent about the latter, but they are intertwined more often than not and may both change at the same time. Lumping everything that's changed under the category of "policy" just because it changed is more useless circular logic.

I had more success rationalizing the church's lack of financial transparency, but it fits into this general trend and illustrates the scope of the problem. The church used to share itemized financial reports in General Conference but stopped in 1960 in order to conceal the $8 million deficit created by Henry D. Moyle's overenthusiastic chapel-building program (which grew to a $32 million deficit by 1962). Apologists point out the obvious fact that it isn't required by American law to disclose its finances. I don't think that not being legally required to do something is a good enough reason for not doing it, and I think tithepayers deserve a clearer picture of where their money is going. Still, I faithfully paid tithing for most of my adult life despite never noticing the promised blessings. (Once, the very evening of the day that I paid tithing, I developed a toothache that ended up costing me well over a thousand dollars because I live in the United States, and two days after I paid tithing, my laptop's hard drive failed and cost me six hundred more.) In December 2019 a whistleblower exposed the church's $100 billion Ensign Peak "rainy day" fund. I don't know if the church actually violated any tax laws as he alleged, or whether Jesus would want it to spend more money on humanitarian aid and less on real estate development, but at a minimum I am annoyed that it tried to keep this fund a secret. Roger Clarke, the head of Ensign Peak, admitted that the church was afraid members would stop paying tithing if they knew how much money it had. That's pretty sketchy in my book. I stopped paying tithing a few months before I stopped believing altogether (and didn't notice any subsequent loss of blessings).

Its Stagnation and Decline

The restored church of Jesus Christ is supposed to roll forward like the "stone cut out without hands" and fill the whole earth. I heard many times growing up that it was the fastest growing religion in the country, if not the world, and that its spectacular growth proved it was true. In reality, while its growth rate did impress sociologists in the past, it's flatlined since the late 1980s. As the annual number of baptisms stays roughly the same or declines a bit, the percentage of increase gets smaller with every passing year. The Preach My Gospel manual, the multi-million dollar "I'm a Mormon" ad campaign, the media's "Mormon Moment," the missionary age change, missionaries using social media, and countless exhortations to members to share the gospel with their friends have not altered this trend. (And the current prophet said that the multi-million dollar "I'm a Mormon" ad campaign was a major victory for Satan.) But that's not the worst part. Around the same time that my enthusiasm for converting the world was squelched by the realization that none of my non-member acquaintances gave a crap about the church, I learned from sources run by faithful members, Matthew Martinich and David Stewart, that only something like 35% of members on the records are active and that a solid majority of the remaining ~65% not only don't attend church but don't believe its teachings or self-identify as members at all. Latin American countries that reported some of the most "spectacular" growth in past decades now have some of the lowest activity rates, typically ranging from 10-20%. The Jehovah's Witnesses and Seventh Day Adventists, similar but supposedly less inspired non-traditional high-demand proselytizing groups, both formed after The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and have reached much higher membership totals with much higher activity rates.

Following a general trend of Christianity, the retention rate of members born in the church has decreased with each succeeding generation. Rhetoric has shifted from "The church is true because it's growing so fast" to "The church is true because it's not shrinking (yet)." Many of the people leaving are among its best and brightest, but that hasn't stopped condescending and scripturally ignorant members from labeling their exodus as "separation of the wheat from the tares." There is no sign of this trend leveling out or reversing. I was alarmed when Young Men general president Brad Wilcox's awful talk in February 2022 demonstrated loud and clear that church leaders are very concerned about it and entirely clueless on how to address it. They are, their insistence to the contrary notwithstanding, out of touch with what young people need and want to help them stay in the church. We are not impressed by glib denials of its racist history, mocking dismissals of concerns over its gender roles, or desperate scare tactics about how our lives will be ruined if we leave. We all have friends and family members who have left the church and are doing just fine. Ex-members outnumbered members in my graduate school cohort two to one. I was further alarmed a few months later when my interview process to be an FSY counselor abruptly ended because several FSY sessions were canceled due to unexpected low enrollment. The church had slashed the price and sent leaders like Brad Wilcox around hyping it up to the max, and a large percentage of still-active teenagers were just not interested. Yikes. Of course, the church isn't going anywhere. It's survived everything thrown at it and will survive indefinitely. But simple math shows that it's in for a very rough time when all the old people die. I felt more and more like I was on a sinking ship.

Following a general trend of Christianity, the retention rate of members born in the church has decreased with each succeeding generation. Rhetoric has shifted from "The church is true because it's growing so fast" to "The church is true because it's not shrinking (yet)." Many of the people leaving are among its best and brightest, but that hasn't stopped condescending and scripturally ignorant members from labeling their exodus as "separation of the wheat from the tares." There is no sign of this trend leveling out or reversing. I was alarmed when Young Men general president Brad Wilcox's awful talk in February 2022 demonstrated loud and clear that church leaders are very concerned about it and entirely clueless on how to address it. They are, their insistence to the contrary notwithstanding, out of touch with what young people need and want to help them stay in the church. We are not impressed by glib denials of its racist history, mocking dismissals of concerns over its gender roles, or desperate scare tactics about how our lives will be ruined if we leave. We all have friends and family members who have left the church and are doing just fine. Ex-members outnumbered members in my graduate school cohort two to one. I was further alarmed a few months later when my interview process to be an FSY counselor abruptly ended because several FSY sessions were canceled due to unexpected low enrollment. The church had slashed the price and sent leaders like Brad Wilcox around hyping it up to the max, and a large percentage of still-active teenagers were just not interested. Yikes. Of course, the church isn't going anywhere. It's survived everything thrown at it and will survive indefinitely. But simple math shows that it's in for a very rough time when all the old people die. I felt more and more like I was on a sinking ship.

Its Prideful Insularity and Persecution Complex

At its best, the church encourages members to seek truth wherever it's found, whether in science or philosophy or any of the world's other religions. At its worst, it sends out its Young Men general president to openly mock the other 99.35% of the world's Christians for "playing church" because they don't have God's permission to worship him. There's a constant tension between these two strains of thought, and unfortunately in my experience the latter is winning. Most of the Sunday school classes I've been in favored simple platitudes over deep thinking, and I felt like I could never ask a difficult question or share anything that wasn't an "approved" answer. Maybe the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints is the truest religion on Earth, but I'm convinced that it knows a lot less about God than it thinks it does, and that it could stand to learn a lot more than it does from the other religions - and I don't just mean other Christian denominations - that in most cases have been around for a lot longer. I'm convinced that while anyone can speak to and be spoken to by God, and the church may do the best job of teaching this principle, actually "knowing" spiritual truths is much more difficult than the average testimony meeting would suggest. Faith is different than empirical knowledge for a reason. Many people who aren't Latter-day Saints believe just as strongly that their religion is true. How can a Latter-day Saint be certain that none of those religions are true (or as true) without experiencing them all firsthand, reading their scriptures and participating in their worship? And if the church didn't place so much emphasis on objective truth claims and on being more correct and more inspired than all other religions, I would be much more able to accept its shortcomings and participate despite my reservations, as people routinely do in most religions.

Much of the problem stems from the 1950s. After the death of John A. Widtsoe, the last scientist in the Quorum of the Twelve (ever), church doctrine took a hard fundamentalist turn under the influence of Joseph Fielding Smith and his son-in-law Bruce R. McConkie, who freely borrowed evangelical Christian views on the nature of scripture. They believed and consequently persuaded most Latter-day Saints to believe that scripture was the final inerrant authority on secular as well as spiritual truth, and that it could always be understood at face value without considering historical or cultural context. This approach is a straight-up recipe for atheism when one actually reads the Old Testament instead of cherry-picking around all the weird and disturbing parts. From the 1960s onward, church manuals were deliberately dumbed down so that a convert of three weeks could use them to teach a lesson. In fairness, this was largely due to the pressure of rapidly growing membership in non-English-speaking countries, but the result was a massive decline in scriptural literacy and critical thinking that left the membership unprepared for the twenty-first century. When Daniel C. Peterson served on the Gospel Doctrine Writing Committee, he was "allowed only to have bullet points, scriptural references, and Life Applicational questions" and was accused of "trying to show off" for wanting to include some helpful background on the political situations alluded to in Isaiah and Jeremiah. Armand Mauss observed in 1994, "The pedagogical posture of the CES has become increasingly anti‑scientific and anti‑intellectual, more inward looking, more intent on the uniqueness and exclusiveness of the Mormon version of the gospel as opposed to other interpretations, whether religious or scientific. Lesson manuals still occasionally take gratuitous swipes at scientists, intellectuals, and modernist ideas, which are blamed for jeopardizing students' testimonies. Non‑Mormon sources and resources are rarely used and highly suspect." This is clearly wrong if "the glory of God is intelligence."

This brings me to the ubiquitous "us vs. the world" rhetoric. I don't want to overstate it because I've rarely gotten as much of a fearmongering vibe as some liberal members or outside observers do. It is, however, a repeated theme within the church that the world is constantly getting worse and will continue to get worse until the Second Coming. My study of history has convinced me otherwise. Yeah, the world is a dumpster fire, but it always has been. It only seems to be getting worse because a. people tend to remember the past through rose-colored glasses and b. the global communication network keeps us constantly informed of every bad thing that happens anywhere in the world. In many ways the world has gotten better. The old white American men leading the church remember the 1950s as a time of strong nuclear families and traditional moral values, and they forget what a horrible time it was to be alive if you were black, female, gay, or a child with polio. And since then, actual statistics show that global literacy, democracy, and life expectancy have skyrocketed while extreme poverty, homicides, and bullying have plummeted. I would like Americans to also recognize that only one country has school shootings on a regular basis. So the church's fear and almost universally negative portrayals of "the world" seem out of proportion to me. John 3:16 says that God loved the world. I'd still appreciate it if his Son came back someday and put out the dumpster fire with a bigger and more literal fire, but I certainly don't expect it within my lifetime. Christians have believed the Second Coming would happen in their lifetimes for nearly two thousand years. I don't see what makes this time different.

Much of the problem stems from the 1950s. After the death of John A. Widtsoe, the last scientist in the Quorum of the Twelve (ever), church doctrine took a hard fundamentalist turn under the influence of Joseph Fielding Smith and his son-in-law Bruce R. McConkie, who freely borrowed evangelical Christian views on the nature of scripture. They believed and consequently persuaded most Latter-day Saints to believe that scripture was the final inerrant authority on secular as well as spiritual truth, and that it could always be understood at face value without considering historical or cultural context. This approach is a straight-up recipe for atheism when one actually reads the Old Testament instead of cherry-picking around all the weird and disturbing parts. From the 1960s onward, church manuals were deliberately dumbed down so that a convert of three weeks could use them to teach a lesson. In fairness, this was largely due to the pressure of rapidly growing membership in non-English-speaking countries, but the result was a massive decline in scriptural literacy and critical thinking that left the membership unprepared for the twenty-first century. When Daniel C. Peterson served on the Gospel Doctrine Writing Committee, he was "allowed only to have bullet points, scriptural references, and Life Applicational questions" and was accused of "trying to show off" for wanting to include some helpful background on the political situations alluded to in Isaiah and Jeremiah. Armand Mauss observed in 1994, "The pedagogical posture of the CES has become increasingly anti‑scientific and anti‑intellectual, more inward looking, more intent on the uniqueness and exclusiveness of the Mormon version of the gospel as opposed to other interpretations, whether religious or scientific. Lesson manuals still occasionally take gratuitous swipes at scientists, intellectuals, and modernist ideas, which are blamed for jeopardizing students' testimonies. Non‑Mormon sources and resources are rarely used and highly suspect." This is clearly wrong if "the glory of God is intelligence."

This brings me to the ubiquitous "us vs. the world" rhetoric. I don't want to overstate it because I've rarely gotten as much of a fearmongering vibe as some liberal members or outside observers do. It is, however, a repeated theme within the church that the world is constantly getting worse and will continue to get worse until the Second Coming. My study of history has convinced me otherwise. Yeah, the world is a dumpster fire, but it always has been. It only seems to be getting worse because a. people tend to remember the past through rose-colored glasses and b. the global communication network keeps us constantly informed of every bad thing that happens anywhere in the world. In many ways the world has gotten better. The old white American men leading the church remember the 1950s as a time of strong nuclear families and traditional moral values, and they forget what a horrible time it was to be alive if you were black, female, gay, or a child with polio. And since then, actual statistics show that global literacy, democracy, and life expectancy have skyrocketed while extreme poverty, homicides, and bullying have plummeted. I would like Americans to also recognize that only one country has school shootings on a regular basis. So the church's fear and almost universally negative portrayals of "the world" seem out of proportion to me. John 3:16 says that God loved the world. I'd still appreciate it if his Son came back someday and put out the dumpster fire with a bigger and more literal fire, but I certainly don't expect it within my lifetime. Christians have believed the Second Coming would happen in their lifetimes for nearly two thousand years. I don't see what makes this time different.

Its Toxic and Stupid Culture

Many times I've heard the faith-affirming cliche "The church is perfect, but the people aren't." I believed that until I figured out that it's as logically incoherent as saying "The body is perfect, but the cells aren't." The church is the people. Without them it has nothing. Okay, so it's true that we shouldn't discredit the teachings and values of the church just because a member mistreats or offends us. But humans are social creatures and religion is a social venture, and we can't just dismiss the potential for a church culture to "squeeze out" people who don't fit the mold and don't want to. In fairness, I can count on one - okay, two hands the people in my entire in-person church experience that I've genuinely disliked. Most of my experience with toxic and stupid Latter-day Saints was on social media and in Deseret News comments sections. Here, faith-affirming myths and cliches are encouraged and rewarded to an alarming degree, uncomfortable facts are overtly denied, and gospel principles are freely interchanged with Republican talking points. Gogo Goff is a respected LDS influencer even though (or because) he's one of the worst people in the world. I'd like to believe that they're just a really small and really loud minority, but it doesn't look like it to me. They're just following in the footsteps of the crackpots that past leaders gave free reign to influence the church, like the John Birch Society, W. Cleon Skousen, and the BYU professor who wrote the dishonest Old Testament institute student manual section on evolution that hasn't been updated in 42 years. I felt very embarrassed to be affiliated with them, and I had to ask why the restored gospel of Jesus Christ creates an environment where they thrive while thoughtful, nuanced, and/or decent people feel marginalized. Culture doesn't magically spring up in a vacuum. Most of it can be traced back to church teachings past or present.

I used to be a diehard conservative politically and religiously, but as my views drifted further to the left with more information and life experience, I became increasingly uncomfortable with my faith community's mindless allegiance to one side of the political spectrum and its worship of the most corrupt and dishonest president in American history. No matter how many times the First Presidency says things to the effect of "Principles compatible with the gospel may be found in various political parties," members of The Church of Donald J. Trump of Latter-day Republicans continue to assert that no faithful member of the church can be a Democrat. (I'm an independent, but that's still wrong.) Even apostle Dieter F. Uchtdorf drew their outrage for "supporting baby killers" and "voting against life" - because many of them base their entire political philosophy on abortion for some unclear reason - after the media revealed that his family had donated to Biden's campaign. (What a shock that a refugee from 1940s Czechoslovakia didn't support the same candidate as every Nazi and white supremacist in America.) I hasten to add that, aside from the occasional idiot bearing their "testimony" that protests against Trump's Muslim ban were part of "the wickedness of the last days" or that "social justice and reproductive justice aren't really justice," the foregoing does not reflect my experience in YSA wards in Utah for the last decade or so. My childhood branch in New York was a different story. The tension between conservative and liberal members nearly tore it apart. I regret my role in that, but I was just following my conservative parents' lead. As a seminary teacher, my dad told my class to be satisfied with what we had and not listen to people who say (in a mocking, whiney voice), "He has more than me; that's not fair" - even though the Book of Mormon unambiguously condemns wealth inequality. (You know what it doesn't condemn? Same-sex marriage.)

I've been disgusted by many American Latter-day Saints' responses to pretty much everything in the last few years. (And make no mistake, this is still an American church.) When church leaders urged us to welcome refugees into our communities, these members supported efforts to ban them from the United States altogether. When leaders took the Covid-19 pandemic seriously and urged us to follow public health guidelines, these members claimed it was a hoax and threw literal temper tantrums about infringements of their God-given right to breathe on strangers. When leaders urged us to get vaccinated, these members engaged in pathetic mental gymnastics to lie to themselves and others that they didn't really mean it. When leaders called on us to root out racism, these members denied its existence, defended police brutality, claimed that Black Lives Matter was a terrorist group, expressed a pathological fear of critical race theory despite not knowing what it is, and bitched about getting a federal holiday to celebrate the end of slavery. When leaders called on us to peacefully accept the results of elections, these members parroted easily disproven lies and conspiracy theories about widespread vote fraud. And these are the hypocrites who for years have loudly accused liberal members of apostasy for being pro-choice and/or supporting same-sex marriage. Of course they have a right to disagree with the church just as I or anyone does, but I have no respect for when and why they've chosen to disagree. Their disagreements are founded on xenophobia, objectively false perceptions of reality, and an obsession with personal convenience that's entirely incompatible with Christian selflessness (or a functional society). The church is apparently afraid to alienate its conservative majority still further, because it refuses to denounce the rise of the alt-right secret combination Deseret Nation (DezNat), a loose social media collective that covers faithful members who think women's suffrage should be repealed and transgender people should be executed.

I used to be a diehard conservative politically and religiously, but as my views drifted further to the left with more information and life experience, I became increasingly uncomfortable with my faith community's mindless allegiance to one side of the political spectrum and its worship of the most corrupt and dishonest president in American history. No matter how many times the First Presidency says things to the effect of "Principles compatible with the gospel may be found in various political parties," members of The Church of Donald J. Trump of Latter-day Republicans continue to assert that no faithful member of the church can be a Democrat. (I'm an independent, but that's still wrong.) Even apostle Dieter F. Uchtdorf drew their outrage for "supporting baby killers" and "voting against life" - because many of them base their entire political philosophy on abortion for some unclear reason - after the media revealed that his family had donated to Biden's campaign. (What a shock that a refugee from 1940s Czechoslovakia didn't support the same candidate as every Nazi and white supremacist in America.) I hasten to add that, aside from the occasional idiot bearing their "testimony" that protests against Trump's Muslim ban were part of "the wickedness of the last days" or that "social justice and reproductive justice aren't really justice," the foregoing does not reflect my experience in YSA wards in Utah for the last decade or so. My childhood branch in New York was a different story. The tension between conservative and liberal members nearly tore it apart. I regret my role in that, but I was just following my conservative parents' lead. As a seminary teacher, my dad told my class to be satisfied with what we had and not listen to people who say (in a mocking, whiney voice), "He has more than me; that's not fair" - even though the Book of Mormon unambiguously condemns wealth inequality. (You know what it doesn't condemn? Same-sex marriage.)

I've been disgusted by many American Latter-day Saints' responses to pretty much everything in the last few years. (And make no mistake, this is still an American church.) When church leaders urged us to welcome refugees into our communities, these members supported efforts to ban them from the United States altogether. When leaders took the Covid-19 pandemic seriously and urged us to follow public health guidelines, these members claimed it was a hoax and threw literal temper tantrums about infringements of their God-given right to breathe on strangers. When leaders urged us to get vaccinated, these members engaged in pathetic mental gymnastics to lie to themselves and others that they didn't really mean it. When leaders called on us to root out racism, these members denied its existence, defended police brutality, claimed that Black Lives Matter was a terrorist group, expressed a pathological fear of critical race theory despite not knowing what it is, and bitched about getting a federal holiday to celebrate the end of slavery. When leaders called on us to peacefully accept the results of elections, these members parroted easily disproven lies and conspiracy theories about widespread vote fraud. And these are the hypocrites who for years have loudly accused liberal members of apostasy for being pro-choice and/or supporting same-sex marriage. Of course they have a right to disagree with the church just as I or anyone does, but I have no respect for when and why they've chosen to disagree. Their disagreements are founded on xenophobia, objectively false perceptions of reality, and an obsession with personal convenience that's entirely incompatible with Christian selflessness (or a functional society). The church is apparently afraid to alienate its conservative majority still further, because it refuses to denounce the rise of the alt-right secret combination Deseret Nation (DezNat), a loose social media collective that covers faithful members who think women's suffrage should be repealed and transgender people should be executed.

Its History (and Present) of Racism

The church's history of racist teachings and practices is well known (Brad Wilcox's prevarications notwithstanding) and I won't rehash it in detail here (especially because I've already done so elsewhere). Current leaders and members have retroactively downgraded them to "theories," "speculation," and "folklore," but virtually none of the leaders and members who propogated them ever referred to them as such. Studying this issue for over a decade has left me with less peace of mind than I started with. The only explanation apologists can give is that prophets and apostles aren't perfect and were influenced by their culture. Fair enough, but that still begs the question of why the Father of all humankind prioritized advising them not to drink coffee over telling them their racist views were wrong. And it's much too generous to give them a free pass because "everyone was racist back then." (Where "everyone" means "white people," of course.) Other, supposedly less inspired religious leaders denounced slavery at the same time Brigham Young taught that it was ordained of God and pushed for its legalization in the Utah Territory. Other, supposedly less inspired religious leaders supported the civil rights movement at the same time Ezra Taft Benson taught that it was a Communist conspiracy and other apostles freaked out over the prospect of racial integration leading to interracial marriage. The church's own breakoff sect, the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints (now Community of Christ), received a revelation against racial discrimination in 1865 and never barred black men from the priesthood.

In keeping with its lack of transparency, the church has done an abysmal job of reckoning with this history. It has frequently acknowledged the 1978 revelation restoring the priesthood and temple blessings to people of black African descent, but it has whitewashed (pun intended) the origins and racist underpinnings of the 126-year ban, and still struggles to attract or retain converts of black African descent. In the 1990s, when African-American members petitioned the church to officially repudiate its racist teachings, Gordon B. Hinckley said that he'd been to Africa and none of the black people there were complaining, so he didn't see anything more that needed to be done. The church suddenly changed its mind in 2012 when Mitt Romney's presidential campaign brought it under international scrutiny and the Washington Post quoted BYU professor Randy Bott saying the same racist things he had taught in his classes for years. It disavowed his statements without mentioning where he got them from. Almost two years later it was more candid about its racist teachings in a Gospel Topics essay, and disavowed all of them without apologizing. Many African-American members still yearn for an apology to bring them more closure and facilitate the church's institutional repentance. In 2020, after George Floyd was murdered, members of the First Presidency started speaking out against racism at the same time as everyone else in the United States - a welcome move, but not a prophetic one by any stretch. They had many chances to be prophetic about this and they weren't. It will take a very long time and a lot more effort before the number of anti-racist statements by church leaders even approaches the number of racist statements by church leaders.

In summer of 2021 I was at a YSA activity in Logan, Utah where two people young enough to know better told racist jokes about black people and Mexicans, and everyone except me laughed. My godless English department friends and colleagues would never have told such jokes. I didn't want to embarrass anyone, so I didn't say anything. I regret that. In September, the US Department of Justice slammed Davis School District (in Davis County, Utah, which is 77% LDS) for its long-term pattern of "deliberate indifference" to "severe, pervasive, and objectively offensive race-based harassment" by students and faculty against black and Asian students. On November 6 in that same school district, ten-year-old Isabella "Izzy" Tichenor hanged herself after months of being bullied for her race and her autism. I think it's a stretch to claim, as some have, a straight line between Brigham Young's racist teachings in the nineteenth century and Utah schoolchildren's racist bullying in the 2010s, as the latter included no theological overtones and consisted of the same generic slurs one might hear anywhere in the United States. But the church's past racism is a primary reason for Utah's lack of racial diversity, which leads to ignorance, and it probably could have changed this culture if it had made any real effort to root out racism before 2020,. Gay children in the church fear God's wrath. Racist children (and adults) in the church obviously don't. In my judgment, its priorities are very warped.

In keeping with its lack of transparency, the church has done an abysmal job of reckoning with this history. It has frequently acknowledged the 1978 revelation restoring the priesthood and temple blessings to people of black African descent, but it has whitewashed (pun intended) the origins and racist underpinnings of the 126-year ban, and still struggles to attract or retain converts of black African descent. In the 1990s, when African-American members petitioned the church to officially repudiate its racist teachings, Gordon B. Hinckley said that he'd been to Africa and none of the black people there were complaining, so he didn't see anything more that needed to be done. The church suddenly changed its mind in 2012 when Mitt Romney's presidential campaign brought it under international scrutiny and the Washington Post quoted BYU professor Randy Bott saying the same racist things he had taught in his classes for years. It disavowed his statements without mentioning where he got them from. Almost two years later it was more candid about its racist teachings in a Gospel Topics essay, and disavowed all of them without apologizing. Many African-American members still yearn for an apology to bring them more closure and facilitate the church's institutional repentance. In 2020, after George Floyd was murdered, members of the First Presidency started speaking out against racism at the same time as everyone else in the United States - a welcome move, but not a prophetic one by any stretch. They had many chances to be prophetic about this and they weren't. It will take a very long time and a lot more effort before the number of anti-racist statements by church leaders even approaches the number of racist statements by church leaders.

In summer of 2021 I was at a YSA activity in Logan, Utah where two people young enough to know better told racist jokes about black people and Mexicans, and everyone except me laughed. My godless English department friends and colleagues would never have told such jokes. I didn't want to embarrass anyone, so I didn't say anything. I regret that. In September, the US Department of Justice slammed Davis School District (in Davis County, Utah, which is 77% LDS) for its long-term pattern of "deliberate indifference" to "severe, pervasive, and objectively offensive race-based harassment" by students and faculty against black and Asian students. On November 6 in that same school district, ten-year-old Isabella "Izzy" Tichenor hanged herself after months of being bullied for her race and her autism. I think it's a stretch to claim, as some have, a straight line between Brigham Young's racist teachings in the nineteenth century and Utah schoolchildren's racist bullying in the 2010s, as the latter included no theological overtones and consisted of the same generic slurs one might hear anywhere in the United States. But the church's past racism is a primary reason for Utah's lack of racial diversity, which leads to ignorance, and it probably could have changed this culture if it had made any real effort to root out racism before 2020,. Gay children in the church fear God's wrath. Racist children (and adults) in the church obviously don't. In my judgment, its priorities are very warped.

Its History (and Present) of Sexism

The church conditioned me from an early age not to recognize sexism when it was right in front of me. I resent that. It taught me that any perceived similarity between its divinely ordained gender roles and the misogyny that's permeated the secular world for most of human history was entirely coincidental and reflected a lack of understanding. When a friend from high school asked me why women in our church had to promise to serve their husbands in heaven as kings, I had never heard of anything like that but I was confident that the church wasn’t sexist, so I told her it wasn’t true. Flash-forward to January 2019 when the media reported the temple ceremony changes and I realized what she had been talking about. Before 2019, women had covenanted to "hearken unto the counsel of" their husbands; before 1990, they had covenanted to "obey the law of" their husbands. I felt punched in the stomach. Then I felt gaslit when leaders and members claimed that changing the terms and parties of the covenant hadn't changed the covenant. In fairness, since 1990 it was explicitly contingent on the husband following God and couldn't reasonably be used to justify abuse - though I know a couple of women whose husbands used it to justify abuse anyway - but making a grown woman mediate her relationship with God through a man is repugnant to me no matter how benevolent he is. Many women were blindsided, hurt, and confused by this unexpected gender hierarchy in the most sacred place on Earth during what was supposed to be a spiritual highlight of their lives. Many found peace only by pretending this covenant meant something different than what it said. If it really did, then it should have gotten more explanation in the temple than none at all. In keeping with the church's lack of transparency, the First Presidency told members not to discuss these changes and never acknowledged the distraught women who had desired them for years.

The male breadwinner / female homemaker model of marriage that I learned as a youth wasn't codified into American society until after World War II, when soldiers returned home and squelched the burgeoning feminist movement by taking their factory jobs back from women, and church leaders didn't claim it as God's eternal truth until the 1960s. After I broke through the church's conditioning I realized it was and is sexist to tell women that their individual talents and interests and dreams don't matter because the divine destiny of everyone with a uterus is to do menial household chores that either sex can do just as well. In keeping with the church's lack of transparency, it quietly phased out this teaching without disavowing it or explaining why it no longer applies, so my most recent bishop thinks it's still doctrine. Leaders also used to use the phrase "patriarchal order of marriage," and when they said that the husband "presided," they actually meant - as the dictionary definitions of the word would suggest - that he was in charge because he had the priesthood. But since the 1990s they've quietly redefined "preside" to mean almost nothing and talked simultaneously about "equal partnership" in marriage without addressing the obvious contradiction. (For example, L. Tom Perry taught in 2004 that husbands and wives are "co-presidents" even though "president" comes from "preside," and the husband is the "leader" but he doesn't "walk ahead of his wife" even though that's what "leading" means, and husbands and wives actually lead "jointly and unanimously" even though the husband is the leader.) You can say there's no contradiction, just like you can say a triangle has 270 degrees, but that doesn't make it so. It is true in theory that "equality doesn't mean sameness," and yet in practice, "separate but equal" has never been true for women any more than it was for black people.

Leaders frequently gush about how wonderful and important women are. That wouldn't be necessary if the church wasn't sexist; its actions would speak louder than words. In addition to the temple thing, many policy changes have been made in recent years (since about the time Ordain Women was founded) to expand women's roles in the church. That wouldn't be necessary if the church wasn't sexist; there was no reason for women not to witness baptisms or sealings before 2019 and there's no reason for them not to be ward clerks and Sunday school presidents right now. Apologists often rationalize how teachings or practices that seem sexist might not really be sexist if you look at them a certain way. That wouldn't be necessary if the church wasn't sexist; nobody has ever struggled with their faith because of the perception that it treats men unfairly. Rhetoric that's used to deny women real authority and influence in the church, usually by telling them how special and superior to men they are, is very similar to rhetoric that was once used to deny them the vote and discourage them from entering the workplace. One of the final straws for my testimony was learning that the church's insurance company refuses to cover birth control, even though the church handbook says that family size is a personal decision, and even if a doctor has determined that a woman needs it for a chronic medical condition. (In another example of a doctrinal change that most members would wrongly classify as a policy change, church leaders used to teach that birth control was evil. Apparently they still believe that despite pretending otherwise.) It has never been more obvious to me that the church does not value or honor women.

The male breadwinner / female homemaker model of marriage that I learned as a youth wasn't codified into American society until after World War II, when soldiers returned home and squelched the burgeoning feminist movement by taking their factory jobs back from women, and church leaders didn't claim it as God's eternal truth until the 1960s. After I broke through the church's conditioning I realized it was and is sexist to tell women that their individual talents and interests and dreams don't matter because the divine destiny of everyone with a uterus is to do menial household chores that either sex can do just as well. In keeping with the church's lack of transparency, it quietly phased out this teaching without disavowing it or explaining why it no longer applies, so my most recent bishop thinks it's still doctrine. Leaders also used to use the phrase "patriarchal order of marriage," and when they said that the husband "presided," they actually meant - as the dictionary definitions of the word would suggest - that he was in charge because he had the priesthood. But since the 1990s they've quietly redefined "preside" to mean almost nothing and talked simultaneously about "equal partnership" in marriage without addressing the obvious contradiction. (For example, L. Tom Perry taught in 2004 that husbands and wives are "co-presidents" even though "president" comes from "preside," and the husband is the "leader" but he doesn't "walk ahead of his wife" even though that's what "leading" means, and husbands and wives actually lead "jointly and unanimously" even though the husband is the leader.) You can say there's no contradiction, just like you can say a triangle has 270 degrees, but that doesn't make it so. It is true in theory that "equality doesn't mean sameness," and yet in practice, "separate but equal" has never been true for women any more than it was for black people.

Leaders frequently gush about how wonderful and important women are. That wouldn't be necessary if the church wasn't sexist; its actions would speak louder than words. In addition to the temple thing, many policy changes have been made in recent years (since about the time Ordain Women was founded) to expand women's roles in the church. That wouldn't be necessary if the church wasn't sexist; there was no reason for women not to witness baptisms or sealings before 2019 and there's no reason for them not to be ward clerks and Sunday school presidents right now. Apologists often rationalize how teachings or practices that seem sexist might not really be sexist if you look at them a certain way. That wouldn't be necessary if the church wasn't sexist; nobody has ever struggled with their faith because of the perception that it treats men unfairly. Rhetoric that's used to deny women real authority and influence in the church, usually by telling them how special and superior to men they are, is very similar to rhetoric that was once used to deny them the vote and discourage them from entering the workplace. One of the final straws for my testimony was learning that the church's insurance company refuses to cover birth control, even though the church handbook says that family size is a personal decision, and even if a doctor has determined that a woman needs it for a chronic medical condition. (In another example of a doctrinal change that most members would wrongly classify as a policy change, church leaders used to teach that birth control was evil. Apparently they still believe that despite pretending otherwise.) It has never been more obvious to me that the church does not value or honor women.

Its Lack of Space for LGBTQ+ People

The church's theology of sex and gender evolved without any capacity to accomodate the existence of gay, lesbian, intersex, transgender, or non-binary people. In the mid-twentieth century when church leaders could no longer ignore gay men (though they still mostly ignored lesbian women), they reconciled that fact by asserting that homosexuality was an acquired and curable pathology. They said things about homosexuals that were no less vile than their statements about black people. They promoted conversion therapies that traumatized a lot of people and caused a few suicides but never "cured" anyone. (Last year, Dallin H. Oaks publicly lied about this happening during his tenure at BYU.) By the 1990s, they had transitioned to their current stance that "the attraction isn't a sin but acting on it is," which enables straight members to glibly disregard the pain of lifelong loneliness and celibacy that it actually implies. They downplay it further by comparing same-sex attraction to alcoholism (even though alcoholics aren't banned from drinking liquids altogether), insisting that it's no different for straight members who can't get married (but are still allowed to have crushes, date, hold hands, kiss, and try), or getting into pretentious discussions about identity (to obfuscate the basic reality that most gay people just want the same things as most straight people). For a long time I told myself that the Lord's ways are not my ways, and just because I don't like or understand these teachings doesn't mean they're not true. I can't do that anymore. In addition to hundreds that I've read about, I personally know many gay, lesbian, or bisexual people who were miserable in the church and have become happier since leaving it and pursuing lifestyles contrary to its teachings. That makes little or no sense if same-sex relationships are sinful and "wickedness never was happiness." If the church's position is correct, its LGB church members should find happiness and inner peace that outweighs the pain, and those who leave should feel empty and come back. That is overwhelmingly not the case.

The church has made little effort to explain why same-sex relationships are sinful besides "God said so." Given its track record on some of the other things it said that God said, that's not good enough for me. Its most developed explanation is that only marriage between a man and a woman can lead to exaltation, but since it no longer recommends heterosexual marriage as a "cure" for gay people, that's largely moot. Being alone doesn't lead to exaltation either, yet church leaders take as self-evident that it's morally superior to being in the "wrong" kind of marriage that still would at least bring happiness and personal development. The history of the church's activism against homosexuality and same-sex marriage is also disturbingly intertwined with right-wing groups that promote misinformation and pseudoscience, such as the Family Research Council, the National Organization for Marriage, and BYU's own short-lived Institute for Studies in Values and Human Behavior. I've heard people claim that "The Family: A Proclamation to the World" was prophetic because nobody in 1995 expected same-sex marriage to be a thing. In reality, church leaders had been concerned about same-sex marriage since the late 1970s, when it was one of their reasons for opposing the Equal Rights Amendment to the US Constitution, and they used the Family Proclamation to justify their petition to intervene in a Hawaii court battle over same-sex marriage that had been ongoing for four years. Its structure and content, up to and including its "prophetic" warning of societal collapse, were clearly inspired by similar documents produced by conservative evangelical groups - the "Family Manifesto" (Family Forum, 1988), the "Danvers Statement" (Center for Biblical Manhood and Womanhood, 1988), and the book Contract with the American Family (Christian Coalition, May 1995). And in another example of the church's disregard for women, general Relief Society counselors Chieko Okazaki and Aileen Clyde are both on record complaining that the male leaders never consulted them on it or even told them it was in the works.

The church's theology has no answer for why God creates gay people and then forbids them from doing anything gay, but it remains even less developed on intersex, transgender, and non-binary people. Leaders and members seem all but required to pretend that sex and gender are as simple as XX + vagina = female and XY + penis = male (an assertion I often see verbatim on social media), ignoring the abundance of scientific evidence to the contrary that, while sometimes difficult for a layperson to understand, is readily available to anyone with internet access. Intersex people have been known to exist since long before Jesus walked the Earth, and were discussed at length by BYU zoology professor Duane Jeffrey in 1979, yet the church handbook didn't even acknowledge them until 2020. The church's theology has no answer for how to determine the eternal gender of a person whose body has both male and female characteristics. The church's theology has no answer for whether a spirit's gender can be mismatched with a body's sex. (Most members would say no because "God doesn't make mistakes" without explaining why literally everything else that can go wrong with people's bodies does.) The church offers no solution for gender dysphoria. Instead its focus is on punishing members who take the "wrong" steps to resolve it themselves. The church's basic theology could be true and still broad or flexible enough to accomodate anomalies, yet leaders and members treat anomalies as existential threats that they have to pretend don't exist.

The church has made little effort to explain why same-sex relationships are sinful besides "God said so." Given its track record on some of the other things it said that God said, that's not good enough for me. Its most developed explanation is that only marriage between a man and a woman can lead to exaltation, but since it no longer recommends heterosexual marriage as a "cure" for gay people, that's largely moot. Being alone doesn't lead to exaltation either, yet church leaders take as self-evident that it's morally superior to being in the "wrong" kind of marriage that still would at least bring happiness and personal development. The history of the church's activism against homosexuality and same-sex marriage is also disturbingly intertwined with right-wing groups that promote misinformation and pseudoscience, such as the Family Research Council, the National Organization for Marriage, and BYU's own short-lived Institute for Studies in Values and Human Behavior. I've heard people claim that "The Family: A Proclamation to the World" was prophetic because nobody in 1995 expected same-sex marriage to be a thing. In reality, church leaders had been concerned about same-sex marriage since the late 1970s, when it was one of their reasons for opposing the Equal Rights Amendment to the US Constitution, and they used the Family Proclamation to justify their petition to intervene in a Hawaii court battle over same-sex marriage that had been ongoing for four years. Its structure and content, up to and including its "prophetic" warning of societal collapse, were clearly inspired by similar documents produced by conservative evangelical groups - the "Family Manifesto" (Family Forum, 1988), the "Danvers Statement" (Center for Biblical Manhood and Womanhood, 1988), and the book Contract with the American Family (Christian Coalition, May 1995). And in another example of the church's disregard for women, general Relief Society counselors Chieko Okazaki and Aileen Clyde are both on record complaining that the male leaders never consulted them on it or even told them it was in the works.

The church's theology has no answer for why God creates gay people and then forbids them from doing anything gay, but it remains even less developed on intersex, transgender, and non-binary people. Leaders and members seem all but required to pretend that sex and gender are as simple as XX + vagina = female and XY + penis = male (an assertion I often see verbatim on social media), ignoring the abundance of scientific evidence to the contrary that, while sometimes difficult for a layperson to understand, is readily available to anyone with internet access. Intersex people have been known to exist since long before Jesus walked the Earth, and were discussed at length by BYU zoology professor Duane Jeffrey in 1979, yet the church handbook didn't even acknowledge them until 2020. The church's theology has no answer for how to determine the eternal gender of a person whose body has both male and female characteristics. The church's theology has no answer for whether a spirit's gender can be mismatched with a body's sex. (Most members would say no because "God doesn't make mistakes" without explaining why literally everything else that can go wrong with people's bodies does.) The church offers no solution for gender dysphoria. Instead its focus is on punishing members who take the "wrong" steps to resolve it themselves. The church's basic theology could be true and still broad or flexible enough to accomodate anomalies, yet leaders and members treat anomalies as existential threats that they have to pretend don't exist.

BYU

I cannot in good conscience support BYU, and I'm not just saying that because I'm an Aggie. BYU is not the church - it's just owned by the church, funded by the church, operated on the teachings and values of the church, and run almost entirely by members of the church. And in some significant respects it is not a godly institution. I can maintain some historical detachment toward its spy ring against liberal faculty members in 1966 and its witch hunts against closeted gay students in the 60s and 70s. I can roll my eyes at its dress and grooming standards that are half a century out of date. But I have a problem with how its Honor Code enforcement until 2019 prioritized punishment over repentance and fostered a culture of students anonymously ratting each other out. I have a problem with it expelling students who leave the church even though non-members are allowed to attend. I have a problem with its systemic racism that, despite years of complaints from students of color, went ignored and unchecked until George Floyd was murdered. I have a problem with its Honor Code office interrogating and punishing students who reported being sexually assaulted, routinely using the Utah County police database to dig up dirt on them, and lying about it. (Should the Lord be proud that his church's university's police department is the only one in the history of Utah to be decertified, albeit temporarily, for its behavior?) I have a problem with it removing a ban on "homosexual behavior" from the Honor Code mid-semester after students had signed it and telling confused gay and lesbian students that they could now date and hold hands, only for CES commissioner Paul V. Johnson, after waiting two weeks for some unfathomable reason, to imply with evasive politician-speak that they still can't. I have a problem with it violating the HIPAA Privacy Rule and the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association Code of Ethics to cease providing gender-affirming speech therapy to transgender students in its Department of Communication Disorders. I stopped paying tithing so I could support Ukraine instead of BYU.

Its Inability to Address Prophetic Fallability

In January 2022, as part of high-level efforts to staunch the hemorrhaging of members in Europe, Russell M. Nelson's wife Wendy said in a devotional, "My testimony is that prophets of God always speak the truth" and "For this new year let's put an exclamation mark after every statement from a prophet, and a question mark after everything else we read, see, or hear." I very much doubt that helped anyone who was on the fence about leaving or staying. It sure sounded like cult rhetoric to me and a lot of other people, and it summed up a problem in the church for which nobody has given me an adequate solution. Prophets of God have not always spoken the truth. They have gotten many things wrong, sometimes with disastrous and far-reaching consequences. If I had lived in the nineteenth century I would have been most unwise to put an exclamation mark after Brigham Young's statements that race mixing should be punished by death. So why should I put current prophets' social views ahead of my own? How can I know when they're actually speaking the truth? The obvious answer (which J. Reuben Clark suggested) would be through the Holy Ghost, yet it seems odd under the church's paradigm that I could be more in tune with the Holy Ghost than the prophet who's teaching falsehoods. It's also moot because the church teaches that if personal revelation ever contradicts the prophet, it's wrong. The church teaches that faithful members can't pick and choose which parts to accept, and strongly implies that every word of General Conference is from the Lord's mouth. This all-or-nothing approach is demonstrably wrong and, again, has made it even more difficult for me to continue participating.

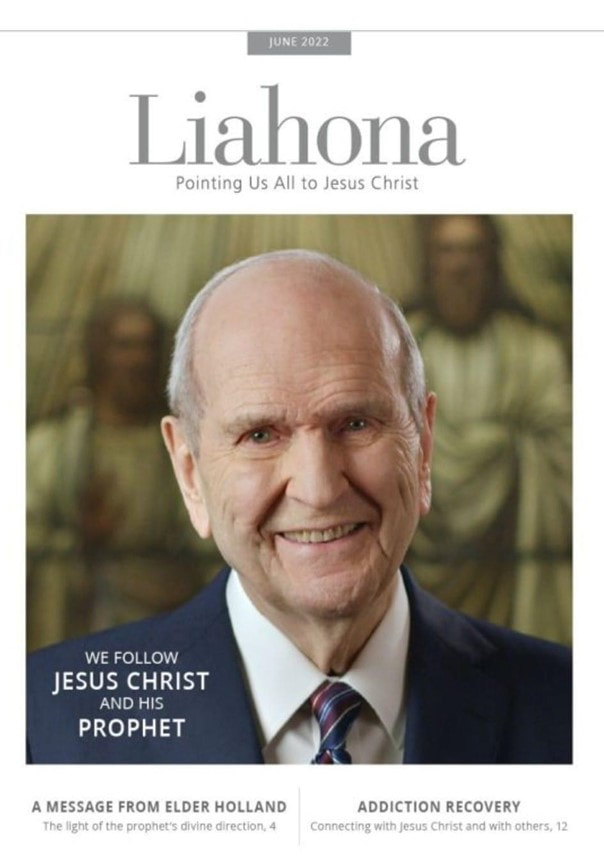

When apologists attempt to address this issue they often victim-blame members for holding facile assumptions of prophetic infallability that they acquired from generations of church talks, magazines, and lesson manuals. (Ezra Taft Benson's influential talk "Fourteen Fundamentals of Following the Prophet" is particularly difficult to interpret as saying anything less than "The prophet is incapable of being wrong about anything at any time.") But at least they're attempting to address it. Church leaders aren't. As members leave in droves for reasons often related to prophetic fallability, the institutional church ignores it completely and doubles down on worshiping Russell M. Nelson. The June 2022 Liahona cover photograph, in which his face fills most of the frame with Heavenly Father and Jesus Christ (literally) out of focus behind him, really drives that point home. I'm no longer taken in by the weird cult of personality around him that neither of his most recent predecessors had. More to the point, I've seen little evidence that he has any special connection to deity that I'm not also entitled to. I don't believe he's a prophet.

When apologists attempt to address this issue they often victim-blame members for holding facile assumptions of prophetic infallability that they acquired from generations of church talks, magazines, and lesson manuals. (Ezra Taft Benson's influential talk "Fourteen Fundamentals of Following the Prophet" is particularly difficult to interpret as saying anything less than "The prophet is incapable of being wrong about anything at any time.") But at least they're attempting to address it. Church leaders aren't. As members leave in droves for reasons often related to prophetic fallability, the institutional church ignores it completely and doubles down on worshiping Russell M. Nelson. The June 2022 Liahona cover photograph, in which his face fills most of the frame with Heavenly Father and Jesus Christ (literally) out of focus behind him, really drives that point home. I'm no longer taken in by the weird cult of personality around him that neither of his most recent predecessors had. More to the point, I've seen little evidence that he has any special connection to deity that I'm not also entitled to. I don't believe he's a prophet.

Conclusion

I did "doubt my doubts." I was not a "lazy learner" or a "lax disciple." I've tried to be an honest seeker of truth, and at this time, my honest truth-seeking has led me outside of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. I appreciate much of what I've learned and gained from the church and I don't intend to throw it all away. I do, however, want to get outside of its conditioning and see it more as outsiders see it. I want to learn in depth about other religions as objectively as I can, without evaluating all of their teachings through the filter of how much they align with what I already believe. I have no predetermined destination in mind and no goal of converting to something else. In all this, my highest priority is my personal relationship with God, which the church taught me to value. I might close my own remarks the same way Stewart Udall closed his Statement of Conscience when he distanced himself from the church seventy-five years ago: "All this is said respectfully, in the realization that the Church contains much that is good, true, and beautiful …. and that it fills a felt need for most of its adherents. I nevertheless feel that I cannot enter into full communion with the church, indeed cannot commune with it at all in good conscience, as long as these attitudes, ideas and principles - and the men who further them - dominate the church."

Addendum: Why I'm Never Coming Back to the LDS Church

May 2023

I was luckier than some. My family, my friends, and my bishop all supported my decision to leave. I made it very slowly, and even so, a lifetime of conditioning and my desire to please God made me second-guess it for a while. Even though I had already given the church far more chances than it deserved, I left open the possibility that I would return someday if my perspective somehow changed and I decided it was true after all. In the meantime, I didn't want to devolve into anger and bitterness like so many ex-Mormons do, and I didn't want to feel like I'd wasted most of my life promoting and defending a lie, so I tried my hardest to maintain a nuanced view of it. Maybe I could hold onto it as a valuable part of my cultural heritage even though I didn't believe it. Maybe, for all its flaws, God still had an important role for it besides fighting against social progress. Maybe the Book of Mormon was still true and Joseph Smith had started out as a true prophet before the church went off the rails. David Whitmer argued this position at great length in his book An Address to All Believers in Christ, which should be required reading for all Latter-day Saints.

But after I left, a family member who had left years earlier reached out to me. He told me he was masculine non-binary transgender and that the church's sexism and transphobia had traumatized him. He called it a "destructive cult." I didn't want to think of it as a destructive cult, but I knew I was coming from a position of privilege. Now that the church's bigotry hit so close to home, I felt guilty for tolerating it for so long. Not long afterward, the church had a sex abuse scandal - not the first one by a long shot, but perhaps the most famous one up to that time, thanks to its coverage by Michael Rezendes, the reporter who won a Pulitzer Prize for exposing the Catholic Church's similar problems. I was appalled that the LDS Church had covered up serial child rape and was now fighting in court to protect the (dead) serial child rapist's privacy and avoid compensating his victims in any way. Its PR department's anonymous response to the first news article was little more than a temper tantrum about how persecuted it was by the evil media. I'm embarrassed to say that I still hesitated and put it off for a few more weeks, but that was the point when I decided to remove my records so that this damnable institution couldn't count me toward its membership statistics. My second-guessing went away after I learned to ask a very simple question: Would an organization led by Jesus Christ behave this way? The answer, in this and far too many other instances, is an obvious no. But as a member, I was trained to do the opposite, to start with the conclusion that it was led by Jesus Christ and try to rationalize its behavior accordingly.

But after I left, a family member who had left years earlier reached out to me. He told me he was masculine non-binary transgender and that the church's sexism and transphobia had traumatized him. He called it a "destructive cult." I didn't want to think of it as a destructive cult, but I knew I was coming from a position of privilege. Now that the church's bigotry hit so close to home, I felt guilty for tolerating it for so long. Not long afterward, the church had a sex abuse scandal - not the first one by a long shot, but perhaps the most famous one up to that time, thanks to its coverage by Michael Rezendes, the reporter who won a Pulitzer Prize for exposing the Catholic Church's similar problems. I was appalled that the LDS Church had covered up serial child rape and was now fighting in court to protect the (dead) serial child rapist's privacy and avoid compensating his victims in any way. Its PR department's anonymous response to the first news article was little more than a temper tantrum about how persecuted it was by the evil media. I'm embarrassed to say that I still hesitated and put it off for a few more weeks, but that was the point when I decided to remove my records so that this damnable institution couldn't count me toward its membership statistics. My second-guessing went away after I learned to ask a very simple question: Would an organization led by Jesus Christ behave this way? The answer, in this and far too many other instances, is an obvious no. But as a member, I was trained to do the opposite, to start with the conclusion that it was led by Jesus Christ and try to rationalize its behavior accordingly.

Oh yes, and then it turned out that the church had gone to such lengths to avoid financial transparency that it actually had broken the law for decades. In February 2023, the Securities Exchange Commission fined Ensign Peak $4 million and the church itself $1 million "for failing to file forms that would have disclosed the Church’s equity investments, and for instead filing forms for shell companies that obscured the Church’s portfolio and misstated Ensign Peak’s control over the Church’s investment decisions." This was done at the direction of the First Presidency and in spite of at least two warnings by the church auditing department (which then continued to read the same verbatim statement in General Conference every April about how everything was fine). Even if systematically going out of its way to violate this very simple law were a mistake - which it wasn't - the church's whole intent was to deceive. I want my tithing back.

As I said, I was familiar with most of the arguments against Joseph Smith and the Book of Mormon for a long time and hadn't found them convincing. The book seemed so complex and authentic when I read it that I could hardly be impressed by critics just saying "Joseph Smith plaiarized it from View of the Hebrews" as if that explained everything. Then I watched the LDS Discussions series on the Mormon Stories podcast. Mike laid out the case against the church's truth claims in a very systematic, chronological way, building off previous episodes and showing the patterns in Smith's behavior in a way that other critics hadn't done. He addressed the apologists' counterarguments and explained why they're ridiculous and often mutually incompatible with each other. I couldn't believe I had ever found them convincing. For the first time, it became not only plausible, but obvious to me that Joseph Smith was a grifter and the Book of Mormon is a nineteenth-century fraud. And I can never unsee the manipulative tactics he used to increase his authority, blame others for his prophetic failures, and convince teenage girls to marry him.

And the worst part is that I had access to most of this information at age seventeen and could have left the church right then instead of giving it the next twelve years of my life. But I had felt "the Spirit" at EFY. The more I learn about "spiritual" feelings, which appear to be the same in every religion and often prompt people to make terrible choices, the more I'm convinced that they're not a reliable means of discerning truth. What I really felt at EFY was elevation emotion induced by my communion with fellow believers in an echo chamber of testimonies, the same thing I could have felt in literally any religion. I might add now that my questioning of God has taken place parallel to but distinct from the deconstruction of the LDS Church that I described above. I was taught to trust the guidance of "the Spirit" and the counsel given to me in priesthood blessings, and that had always worked out for me before, but in late 2021 and early 2022 it brought me some of the biggest pain and disillusionment of my life when something I knew with almost every fiber of my being would happen didn't happen. I had reached this certainty after several months of desperate prayer, fasting, soul-searching, logical analysis, and superhuman patience, at which point I decided to let go of my fear and my doubts and fully trust what I believed God was telling me based on spiritual feelings, spiritual thoughts, priesthood blessings, coincidences that looked like a pattern, and a euphoric semi-visionary experience on the grounds of the Logan Temple. And I was wrong. My Mormon friends tried to comfort me with the usual excuses. "Maybe it was for the next life." "Maybe you misinterpreted it." As much as I appreciate the effort, those excuses are woefully inadequate. Either God intentionally misled me or I was delusional. In either case, I don't think I'm going to ask him to guide my life anymore. And that really sucks and makes the world a much lonelier and scarier place for me.