Continued from "Is the LDS Church Homophobic?"

The LDS Church and Same-Sex Marriage

Though the concept of same-sex marriage had been contemplated at least as early as 1953, it took a long time to emerge as a goal of the gay rights movement. In Ireland, Brendan O'Neill noted, "What we have here is not the politics of autonomy, but the politics of identity. Where the politics of autonomy was about ejecting the state from gay people’s lives - whether it was Stonewall rioters kicking the cops out of their bars or Peter Tatchell demanding the dismantling of all laws forbidding homosexual acts - the politics of identity calls upon the state to intervene in gay people’s lives, and offer them its recognition, its approval. For much of the past 50 years, radical gay-rights activism was in essence about saying ‘We do not need the approval of the state to live how we choose’; now, in the explicit words of The Politics of Same-Sex Marriage, it’s about seeking ‘the sanction of the state for our intimate relationships’. The rise of gay marriage over the past 10 years speaks, profoundly, to the diminution of the culture of autonomy, and its replacement by a far more nervous, insecure cultural outlook that continually requires lifestyle validation from external bodies. And the state is only too happy to play this authoritative role of approver of lifestyles, as evidenced in Enda Kenny’s patronising (yet widely celebrated) comment about Irish gays finally having their ‘fragile and deeply personal hopes realised’."

On the previous page, I explained that the LDS Church's theology enshrines heterosexual marriage as a requirement for the highest level of heaven. It has also focused on heterosexual marriage as a baseline for the family, and the family as the fundamental building block in society. Many understandably wondered, why didn't the church just refuse to offer same-sex marriages within its own ranks and leave everyone else alone? Why did it try to impose its teachings on people who don't believe them? The LDS Church was hardly the only religion that opposed same-sex marriage in the United States and elsewhere through various legal channels, but it was probably the most hypocritical. It had already redefined "traditional" marriage four times: from the 1850s onward it taught that polygyny (one husband and multiple wives) was the Lord's true order of marriage and a requirement for exaltation, in 1890 it began its slow abandonment of polygyny and decided that the Lord's standard was actually monogamy, in the 1980s it quietly stopped opposing interracial marriage, and in the 1990s it quietly replaced its misogynistic "patriarchal order of marriage" with the "equal partners" model that it had explicitly condemned in the preceding decades.

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, the possibility of same-sex marriage was one of the church's stated reasons for opposing the Equal Rights Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. Its focus on that specific issue apparently dates back to late 1984 when former lawyer and new apostle Dallin H. Oaks discussed it in a position paper on "Legislation Affecting Rights of Homosexuals." He wrote, "One generation of homosexual 'marriages' would depopulate a nation, and, if sufficiently widespread, would extinguish its people. Our marriage laws should not abet national suicide." But he also admitted, somewhat more rationally, "There is an irony inherent in the Church's taking a public position against homosexual marriages.... The leading United States Supreme Court authority for the proposition that marriage means a relationship between a man and a woman is Reynolds v. United States, 98 U.S. 145 (1878). In that case, in which the United States Supreme Court sustained the validity of the anti-polygamy laws, the Court defined marriage as a legal union between one man and one woman.... The irony would arise if the Church used as an argument for the illegality of homosexual marriages the precedent formerly used against the Church to establish the illegality of polygamous marriages."

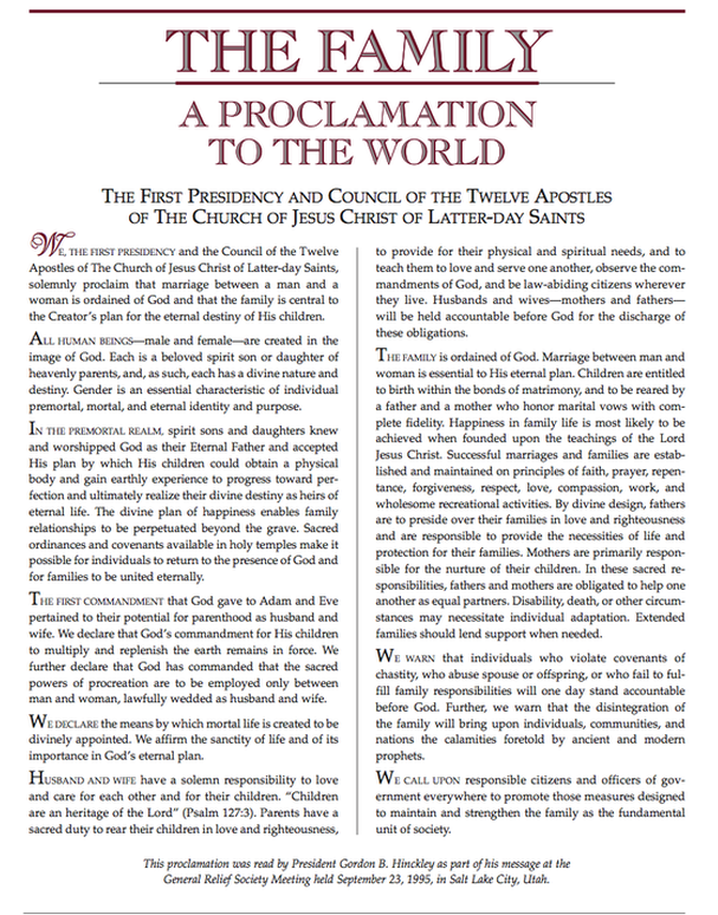

The LDS Church's opposition ramped up during the first US court battle over same-sex marriage, Hawaii's Baehr v. Lewin, beginning in September 1991. In February 1995 the church filed a petition to intervene, but was rejected because it failed to demonstrate any "property or transaction" in the case beyond the arguments already being made. To rectify that, President Gordon B. Hinckley unveiled "The Family: A Proclamation to the World" in September, which clearly outlined the church's position. It drew obvious inspiration from similar documents by other conservative evangelical groups, such as the "Family Manifesto" (Family Forum, 1988), the "Danvers Statement" (Center for Biblical Manhood and Womanhood, 1988), and the book Contract with the American Family (Christian Coalition, May 1995). Both general Relief Society counselors at the time, Chieko Okazaki and Aileen Clyde, later complained that the male leaders never consulted them on it or even told them it was in the works.

On the previous page, I explained that the LDS Church's theology enshrines heterosexual marriage as a requirement for the highest level of heaven. It has also focused on heterosexual marriage as a baseline for the family, and the family as the fundamental building block in society. Many understandably wondered, why didn't the church just refuse to offer same-sex marriages within its own ranks and leave everyone else alone? Why did it try to impose its teachings on people who don't believe them? The LDS Church was hardly the only religion that opposed same-sex marriage in the United States and elsewhere through various legal channels, but it was probably the most hypocritical. It had already redefined "traditional" marriage four times: from the 1850s onward it taught that polygyny (one husband and multiple wives) was the Lord's true order of marriage and a requirement for exaltation, in 1890 it began its slow abandonment of polygyny and decided that the Lord's standard was actually monogamy, in the 1980s it quietly stopped opposing interracial marriage, and in the 1990s it quietly replaced its misogynistic "patriarchal order of marriage" with the "equal partners" model that it had explicitly condemned in the preceding decades.

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, the possibility of same-sex marriage was one of the church's stated reasons for opposing the Equal Rights Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. Its focus on that specific issue apparently dates back to late 1984 when former lawyer and new apostle Dallin H. Oaks discussed it in a position paper on "Legislation Affecting Rights of Homosexuals." He wrote, "One generation of homosexual 'marriages' would depopulate a nation, and, if sufficiently widespread, would extinguish its people. Our marriage laws should not abet national suicide." But he also admitted, somewhat more rationally, "There is an irony inherent in the Church's taking a public position against homosexual marriages.... The leading United States Supreme Court authority for the proposition that marriage means a relationship between a man and a woman is Reynolds v. United States, 98 U.S. 145 (1878). In that case, in which the United States Supreme Court sustained the validity of the anti-polygamy laws, the Court defined marriage as a legal union between one man and one woman.... The irony would arise if the Church used as an argument for the illegality of homosexual marriages the precedent formerly used against the Church to establish the illegality of polygamous marriages."

The LDS Church's opposition ramped up during the first US court battle over same-sex marriage, Hawaii's Baehr v. Lewin, beginning in September 1991. In February 1995 the church filed a petition to intervene, but was rejected because it failed to demonstrate any "property or transaction" in the case beyond the arguments already being made. To rectify that, President Gordon B. Hinckley unveiled "The Family: A Proclamation to the World" in September, which clearly outlined the church's position. It drew obvious inspiration from similar documents by other conservative evangelical groups, such as the "Family Manifesto" (Family Forum, 1988), the "Danvers Statement" (Center for Biblical Manhood and Womanhood, 1988), and the book Contract with the American Family (Christian Coalition, May 1995). Both general Relief Society counselors at the time, Chieko Okazaki and Aileen Clyde, later complained that the male leaders never consulted them on it or even told them it was in the works.

In 2008, the LDS Church was asked to join a coalition of various faiths working to pass Proposition 8 and amend the California Constitution to define marriage as between a man and a woman, repealing the existing right to same-sex marriage in that state (though it still allowed same-sex civil unions, which in California were essentially the same thing under a different name). For the first time its political efforts against same-sex marriage came into the national spotlight and generated considerable outrage. Its members' exceptionally organized campaigning and sizeable financial donations were largely blamed for the proposition's success. Latter-day Saints in California and elsewhere were targeted with protests, threats, vandalism, job loss, and boycotts. In a speech on religious freedom almost a year later, Dallin H. Oaks noted that "these incidents of violence and intimidation are not so much anti-religious as anti-democratic. In their effect they are like the well-known and widely condemned voter-intimidation of blacks in the South that produced corrective federal civil-rights legislation." The next day, liberal commentator Keith Olbermann awarded Oaks one of his nightly slots as "Worst Person in the World" and said, "One would think that with the Mormons' history of being on the wrong side of integration and the wrong side of that pesky ancient order of one woman per marriage, that these are subjects about which Elder Oaks would want to shut the hell up."

Even within the church, many were hurt and confused by this political action that felt at odds with their understanding of both constitutional rights, separation of church and state, and the gospel of Jesus Christ. In 2010 Elder Marlin K. Jensen of the Seventy attended a special meeting of the Oakland California Stake and listened to some of their stories. He reportedly said, "I have heard the calls for change in our church’s policy on this subject. I have read Carol Lynn Pearson’s books and wept as I read them. I don’t think the evolution of our policies will go as far as many would like. Rather I think the evolution will be one of better understanding. I believe our concept of marriage is part of the bedrock of our doctrine and will not change. I believe our policy will continue to be that gay members of the Church must remain celibate. However, I want you to know that as a result of being with you this morning, my aversion to homophobia has grown. I know that many very good people have been deeply hurt, and I know that the Lord expects better of us." The LDS Church was noticeably absent from state-level same-sex marriage debates or legislation during the 2012 election cycle when Mitt Romney, a member, was running for president of the United States.

LDS leaders have rarely given legitimate secular reasons for opposing secular same-sex marriage, but an amicus brief submitted to the US Supreme Court in April 2015, co-signed with eighteen other churches, claimed, "A decision that traditional marriage laws are grounded in animus would demean us and our beliefs. It would stigmatize us as fools or bigots, akin to racists. In time it would impede full participation in democratic life, as our beliefs concerning marriage, family, and sexuality are placed beyond the constitutional pale. It would nullify our votes on key public policy issues - including on the laws before the Court in this case. Because we cannot renounce our scriptural beliefs, a finding of animus would consign us to second-class status as citizens whose religious convictions about vital aspects of society are deemed illegitimate. Assaults on our religious institutions and our rights of free exercise, speech, and association would intensify." Conflicts between gay rights and religious rights have arisen in the United States, starting with Catholic orphanages in Massachusetts, leading to several Christian bakeries, flower shops, and other privately owned institutions facing legal challenges and outpourings of public hatred for refusing to cater same-sex weddings. Some Latter-day Saints believe their church will someday lose its tax-exempt status if it doesn't allow same-sex marriages in its temples.

LDS leaders have rarely given legitimate secular reasons for opposing secular same-sex marriage, but an amicus brief submitted to the US Supreme Court in April 2015, co-signed with eighteen other churches, claimed, "A decision that traditional marriage laws are grounded in animus would demean us and our beliefs. It would stigmatize us as fools or bigots, akin to racists. In time it would impede full participation in democratic life, as our beliefs concerning marriage, family, and sexuality are placed beyond the constitutional pale. It would nullify our votes on key public policy issues - including on the laws before the Court in this case. Because we cannot renounce our scriptural beliefs, a finding of animus would consign us to second-class status as citizens whose religious convictions about vital aspects of society are deemed illegitimate. Assaults on our religious institutions and our rights of free exercise, speech, and association would intensify." Conflicts between gay rights and religious rights have arisen in the United States, starting with Catholic orphanages in Massachusetts, leading to several Christian bakeries, flower shops, and other privately owned institutions facing legal challenges and outpourings of public hatred for refusing to cater same-sex weddings. Some Latter-day Saints believe their church will someday lose its tax-exempt status if it doesn't allow same-sex marriages in its temples.

After the Supreme Court legalized same-sex marriage across the U.S., the LDS Church issued a statement that read in part: "The gospel of Jesus Christ teaches us to love and treat all people with kindness and civility - even when we disagree. We affirm that those who avail themselves of laws or court rulings authorizing same‐sex marriage should not be treated disrespectfully. Indeed, the Church has advocated for rights of same‐sex couples in matters of hospitalization and medical care, fair housing and employment, and probate, so long as these do not infringe on the integrity of the traditional family or the constitutional rights of churches." In November of that year, the church implemented a very controversial policy (identical to the longstanding policy for polygamous families) that categorized same-sex marriage as "apostasy" and denied baby blessings or baptism to children of same-sex couples until they reached age eighteen and disavowed their parents' lifestyle, unless they received special permission from the First Presidency. This policy was allegedly intended to avoid creating conflict between what the children were taught at home and what they were taught at church. Russell M. Nelson claimed it had been revealed to the First Presidency and apostles as the will of the Lord. After huge backlash, mass membership resignations, and deep hurt in and out of the church, Nelson, now president of the church, rescinded the policy.

Though I deeply disagree with them, I understand that the LDS leaders, like other people of faith, are doing what they believe is right. Catholic Professor Robert P. George, a frequent ally of the church, said: "These forces tell us that our defeat in the causes of marriage and human life is inevitable. They warn us that we are on the wrong side of history. They insist that we will be judged by future generations the way we today judge those who championed racial injustice in the Jim Crow south. But history does not have sides. It is an impersonal and contingent sequence of events, events that are determined in decisive ways by human deliberation, judgment, choice, and action. The future of marriage and of countless human lives can and will be determined by our judgments and choices, our willingness or unwillingness to bear faithful witness, our acts of courage or cowardice.

"Nor is history, or future generations, a judge invested with god-like powers to decide, much less dictate, who was right and who was wrong. The idea of a judgment of history is secularism’s vain, meaningless, hopeless, and pathetic attempt to devise a substitute for what the great Abrahamic traditions of faith know is the final judgment of Almighty God. History is not God. God is God. History is not our judge. God is our judge. One day we will give an account of all we have done and failed to do. Let no one suppose that we will make this accounting to some impersonal sequence of events possessing no more power to judge than a golden calf or a carved and painted totem pole. It is before God, the God of truth, the Lord of history, that we will stand. And as we tremble in His presence it will be no use for any of us to claim that we did everything in our power to put ourselves on the right side of history."

Dallin H. Oaks, who had a long history of homophobic statements, acknowledged in late 2021, "As a religious person who has served in government at both federal and state levels and now as a leader in the worldwide Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, I have always known of the tensions experienced when persons who rely on the free exercise of religion are conflicted between duties to God and duties to country. More recently, I have come to understand better the distress of persons who feel that others are invoking constitutional rights like free exercise of religion and freedom of speech to deny or challenge their own core beliefs and their access to basic constitutional rights. I deeply regret that these two groups have been drawn into conflict with one another."

Though I deeply disagree with them, I understand that the LDS leaders, like other people of faith, are doing what they believe is right. Catholic Professor Robert P. George, a frequent ally of the church, said: "These forces tell us that our defeat in the causes of marriage and human life is inevitable. They warn us that we are on the wrong side of history. They insist that we will be judged by future generations the way we today judge those who championed racial injustice in the Jim Crow south. But history does not have sides. It is an impersonal and contingent sequence of events, events that are determined in decisive ways by human deliberation, judgment, choice, and action. The future of marriage and of countless human lives can and will be determined by our judgments and choices, our willingness or unwillingness to bear faithful witness, our acts of courage or cowardice.

"Nor is history, or future generations, a judge invested with god-like powers to decide, much less dictate, who was right and who was wrong. The idea of a judgment of history is secularism’s vain, meaningless, hopeless, and pathetic attempt to devise a substitute for what the great Abrahamic traditions of faith know is the final judgment of Almighty God. History is not God. God is God. History is not our judge. God is our judge. One day we will give an account of all we have done and failed to do. Let no one suppose that we will make this accounting to some impersonal sequence of events possessing no more power to judge than a golden calf or a carved and painted totem pole. It is before God, the God of truth, the Lord of history, that we will stand. And as we tremble in His presence it will be no use for any of us to claim that we did everything in our power to put ourselves on the right side of history."

Dallin H. Oaks, who had a long history of homophobic statements, acknowledged in late 2021, "As a religious person who has served in government at both federal and state levels and now as a leader in the worldwide Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, I have always known of the tensions experienced when persons who rely on the free exercise of religion are conflicted between duties to God and duties to country. More recently, I have come to understand better the distress of persons who feel that others are invoking constitutional rights like free exercise of religion and freedom of speech to deny or challenge their own core beliefs and their access to basic constitutional rights. I deeply regret that these two groups have been drawn into conflict with one another."