In Fall 2013 I took a class from Dr. James Pitts at USU called "Darwin's Big Idea" or something like that. (On hearing this, one of my LDS friends remarked, "Evolution? That's lame. Creationism is the way to go, right?" It was awkward because the class was an elective that I took for fun.) It was far more of a reading and discussion than traditional science class. We read On the Origin of Species, which I found to be mostly filled with indisputable common sense, along with another book about the social and cultural context of evolutionary theory, and discussed them both as well as a ton of other cool stuff. We each had to make a presentation and we each had to choose a tangent topic to write an essay about. This was mine. It got a 98 on the rough draft and 100 on the final.

Given my wholehearted endorsement of modern biology and my disdain for the notion that it's all a big mistake or conspiracy, it may come as a surprise to some that I recognize scientists as being fully human after all. And sometimes, the consensus is wrong and it takes a lone crusader to shake up the orthodoxy and turn it around. Charles Darwin was one of those crusaders and so is one of my heroes, Robert T. Bakker. (Creationists hoped Michael Behe would be one of them too, and anti-vaxxers still think Andrew Wakefield is, but spoiler alert, neither of them are.)

Given my wholehearted endorsement of modern biology and my disdain for the notion that it's all a big mistake or conspiracy, it may come as a surprise to some that I recognize scientists as being fully human after all. And sometimes, the consensus is wrong and it takes a lone crusader to shake up the orthodoxy and turn it around. Charles Darwin was one of those crusaders and so is one of my heroes, Robert T. Bakker. (Creationists hoped Michael Behe would be one of them too, and anti-vaxxers still think Andrew Wakefield is, but spoiler alert, neither of them are.)

Discarding Dated Dinosaur Dogmas: Robert T. Bakker and the Dinosaur Renaissance

By C. Randall Nicholson

One need only browse a picture book about dinosaurs that was written thirty years ago to see that our understanding of these beasts has changed dramatically. Once portrayed as slow, dull-witted creatures that were eclipsed by the more evolutionarily competent mammals, they are now recognized as faster and more intelligent than previously supposed, and able to hold their own in the battle for survival. This change in our way of thinking, now known as the "dinosaur renaissance", reflects improved understanding and more available evidence. It revitalized and rejuvenated a waning interest in dinosaurs among scientists and lay people alike. Yet it did not come without a struggle above and beyond the rigors of research, as it met with resistance from the established scientific community. At the forefront of this struggle was a paleontologist named Robert T. Bakker (pronounced bahk-er).

The Bias Problem

Some may wonder what all the fuss was about. It should be remembered that although science in theory is the objective pursuit of empirical knowledge about the universe, in practice such objectivity can be difficult or impossible to achieve. All human beings carry their own biases and assumptions, and oftentimes these are so deeply ingrained that one cannot recognize them in oneself until an outside observer points them out. Scientists are no different. What may seem to a scientist to be the only logical and obvious conclusion from a set of data may, in fact, be only the way he looks at it because of his bias.

Thus scientists must be conscious of this weakness and try to not let it get in the way of science. They must be willing to change their views. Charles Darwin famously did this when he proposed that natural selection or survival of the fittest was the mechanism behind organic evolution, rather than any of the other ideas that were proposed by scientists of his era and often appealed to divine intervention. Though many great minds have toiled in the name of science, such "revolutionaries" who propose radical new ideas that change its course forever are, on the whole, rare.

Another weakness that plagues most people, and therefore scientists as well, is that of confirmation bias. This is the tendency to give more weight or credence to information that supports their preconceived ideas, and ignore or dismiss that which does not (Ch'ng and Zaharim 2010). Bakker has referred to this more colloquially as the "harrumph-and-amen" syndrome. When a multitude of evidences are assembled challenging traditional dinosaur theories, the orthodoxy snorts and says "Harrumph, this all means nothing." On the other hand, when any small amount of evidence is found to support the old views, it says "Amen, we knew it all the time" (Bakker 1986).

Of course, Bakker himself is also human and therefore not immune to confirmation bias. A New York Times reviewer wrote of his seminal book, “If any fault is to be found in this book, it is the author's tendency to give short shrift to opposing arguments as he rushes to his own conclusions. Sometimes he makes an informed assumption, then, a few pages later, leaves the reader with the impression that the ensuing hypothesis was based on fact, not assumption. These are flaws born of enthusiasm, not deceit” (Wilford 1986). These shortcomings did not detract from the significance of his contributions. In the conversation that followed, a conversation that for too long had been stifled by orthodoxy, they could be worked out with most of the main points remaining valid.

Thus scientists must be conscious of this weakness and try to not let it get in the way of science. They must be willing to change their views. Charles Darwin famously did this when he proposed that natural selection or survival of the fittest was the mechanism behind organic evolution, rather than any of the other ideas that were proposed by scientists of his era and often appealed to divine intervention. Though many great minds have toiled in the name of science, such "revolutionaries" who propose radical new ideas that change its course forever are, on the whole, rare.

Another weakness that plagues most people, and therefore scientists as well, is that of confirmation bias. This is the tendency to give more weight or credence to information that supports their preconceived ideas, and ignore or dismiss that which does not (Ch'ng and Zaharim 2010). Bakker has referred to this more colloquially as the "harrumph-and-amen" syndrome. When a multitude of evidences are assembled challenging traditional dinosaur theories, the orthodoxy snorts and says "Harrumph, this all means nothing." On the other hand, when any small amount of evidence is found to support the old views, it says "Amen, we knew it all the time" (Bakker 1986).

Of course, Bakker himself is also human and therefore not immune to confirmation bias. A New York Times reviewer wrote of his seminal book, “If any fault is to be found in this book, it is the author's tendency to give short shrift to opposing arguments as he rushes to his own conclusions. Sometimes he makes an informed assumption, then, a few pages later, leaves the reader with the impression that the ensuing hypothesis was based on fact, not assumption. These are flaws born of enthusiasm, not deceit” (Wilford 1986). These shortcomings did not detract from the significance of his contributions. In the conversation that followed, a conversation that for too long had been stifled by orthodoxy, they could be worked out with most of the main points remaining valid.

The Old View of Dinosaurs

Besides the standard bias toward conventional wisdom, a sort of prejudice against dinosaurs was the basis of much of that wisdom in the first place. Human nature is to favor the animals that are most like us; i.e. warm-blooded, furry, lactating mammals. In contrast, cold-blooded creatures and reptiles in particular have long been relegated to the lowest rung in a de facto, if not de jure, hierarchy of organisms. In 1758 Carolus Linnaeus summarized this viewpoint when he wrote in the tenth edition of his Systema Naturae: "These foul and loathsome animals are abhorrent because of their cold body, pale color, cartilaginous skeleton, filthy skin, fierce aspect, calculating eye, offensive smell, harsh voice, squalid habitation, and terrible venom; wherefore their Creator has not exerted his powers to make many of them" (Linnaeus 1758).

Bakker also refers to those who disdain reptiles as "mammal chauvinists", and has lamented their views at great length, pointing out that snakes have come to symbolize brute strength without intelligence or honor, and the synonym of deceit and ambush in common slang. After reviewing the greater danger posed to humans by crocodiles compared to that of tigers, lions and leopards, he hastened to add that "in our culture, we react to these reptilian potential man-killers only with revulsion, not with respect. What a difference from the role reserved for mammalian man-eaters – the lion is so admired for strength and cunning that nearly every royal European household placed the tawny beast on its coat of arms, and both the Messiah of the Old Testament and the Emperor of Ethiopia were hailed as the Lion of Judah… [but] not even the shortest-lived Balkan principality adorned its royal crest with a Nile crocodile" (Bakker 1986). Ancient Egyptians worshiped a crocodile god named Sobek and honored crocodiles as pets, but for Western culture at least his point remains.

Dinosaurs, it has long been believed, also fit into this category of "foul and loathsome animals". When Sir Richard Owen coined the term in 1841 he proposed that because of their superficial similarities to modern reptiles, coupled with their differences and superior size, they be classed in "a distinct tribe or sub-order of Saurian Reptiles, for which I would propose the name of Dinosauria" (Owen 1842). This term is from the Latin meaning some variation of "terrible lizard". Organism classification is a difficult endeavor, however, and wrong or insufficient classifications may hinder learning more about their true natures by creating biases, not only against them per se but in the assumptions of what they were supposedly like.

Robert Bakker has said, "Generally speaking badges are harmful in science. If a scientist pins one labeled 'Reptile' on some extinct species, anyone who sees it will automatically think, 'Reptile, hmmm… that means cold-blooded, a lower vertebrate, sluggish when the weather is dark and cool.' There are never enough naturalists around, in any age; so most scientific orthodoxy goes unchallenged. There are just not enough skeptical minds to stare at each badge and ask the embarrassing question, 'How do you know the label is right?'" (Bakker 1986) Bakker was one of these minds and not afraid to make it known. He regards thinking by labels as "pop-top, vending-machine science" and "pretzel logic" (Lindner 1992).

Bakker also refers to those who disdain reptiles as "mammal chauvinists", and has lamented their views at great length, pointing out that snakes have come to symbolize brute strength without intelligence or honor, and the synonym of deceit and ambush in common slang. After reviewing the greater danger posed to humans by crocodiles compared to that of tigers, lions and leopards, he hastened to add that "in our culture, we react to these reptilian potential man-killers only with revulsion, not with respect. What a difference from the role reserved for mammalian man-eaters – the lion is so admired for strength and cunning that nearly every royal European household placed the tawny beast on its coat of arms, and both the Messiah of the Old Testament and the Emperor of Ethiopia were hailed as the Lion of Judah… [but] not even the shortest-lived Balkan principality adorned its royal crest with a Nile crocodile" (Bakker 1986). Ancient Egyptians worshiped a crocodile god named Sobek and honored crocodiles as pets, but for Western culture at least his point remains.

Dinosaurs, it has long been believed, also fit into this category of "foul and loathsome animals". When Sir Richard Owen coined the term in 1841 he proposed that because of their superficial similarities to modern reptiles, coupled with their differences and superior size, they be classed in "a distinct tribe or sub-order of Saurian Reptiles, for which I would propose the name of Dinosauria" (Owen 1842). This term is from the Latin meaning some variation of "terrible lizard". Organism classification is a difficult endeavor, however, and wrong or insufficient classifications may hinder learning more about their true natures by creating biases, not only against them per se but in the assumptions of what they were supposedly like.

Robert Bakker has said, "Generally speaking badges are harmful in science. If a scientist pins one labeled 'Reptile' on some extinct species, anyone who sees it will automatically think, 'Reptile, hmmm… that means cold-blooded, a lower vertebrate, sluggish when the weather is dark and cool.' There are never enough naturalists around, in any age; so most scientific orthodoxy goes unchallenged. There are just not enough skeptical minds to stare at each badge and ask the embarrassing question, 'How do you know the label is right?'" (Bakker 1986) Bakker was one of these minds and not afraid to make it known. He regards thinking by labels as "pop-top, vending-machine science" and "pretzel logic" (Lindner 1992).

The Lone Challengers

Bakker is one of the rare individuals with a gift of questioning everything and looking beyond things that others take for granted. Early on he was re-evaluating and changing the views inherited from the culture and people around him. He grew up in a household of fundamentalist Christians who believed the earth was about 10,000 years old. "In the '60s… I belonged to a conservative Christian campus group and did street preaching," he recalled. His views underwent a shift as he learned about evolution and the true age of the earth, but with characteristic open-mindedness he adapted them rather than discarding them entirely. "Even though I don’t believe them literally anymore, the first five books of the Old Testament still have a lot of meaning for me. My mother is still a creationist, but she has accepted that I can be an evolutionist and still have a spiritual side" (Pearce and Good 1992).

Though he has remained vague about this spiritual side, Bakker evidently sees it as corroboratory to his scientific side. In responding to critics who are skeptical that much can be learned about long-extinct organisms and ecosystems by studying their fossils, he has written that "these views are wrongheaded. The Book of Job – oldest in the Bible – admonishes, 'Speak to the Earth and it will teach thee.' If we look and listen carefully, the record of the rocks can unlock the richly textured story of the dinosaurs and their ways" (Bakker 1986).

In this vein, he visualizes long-dead fossils as living, breathing dinosaurs. He has remarked, "I want to be the Bob DeNiro of the Jurassic. You know DeNiro is a method actor. When he's going to play the part of a bus driver he wants to feel like a bus driver. If I am studying Camptosaurus I want to feel like Camptosaurus. Which has required 20 years of work. I can kind of feel like Camptosaurus, sniff the ground and think, 'It's too wet here. Too swampy I don't want to go there. Oh dry forest! I want to go there.'" (Prehistoric Planet) He has even written a novel, Raptor Red, which describes the Cretaceous period from the perspective of a Utahraptor (Bakker 1995). With this attitude and perspective he has been able to notice details in the fossil record that others had long overlooked.

Therefore, his scientific side underwent as much or more scrutiny than the spiritual one. He became skeptical of traditional dinosaur portrayals from the age of ten, when he read a 1955 Life magazine article called "The World We Live In" and had a moment similar to "Saul's conversion on the road to Damascus" (Lindner 1992) He continued to be skeptical of some of the conventional wisdom he learned as an undergrad at Yale. The prevailing view, as mentioned, was that dinosaurs were evolutionary failures that had been supplanted by superior mammalian species. Thomas Henry Huxley, "Darwin’s Bulldog", had compared the early bird Archaeopteryx with small therapod dinosaurs like Compsognathus in the late 1860s and concluded that dinosaurs evolved from birds rather than other reptiles (Huxley 1868), but gained little support for this view.

In 1964 John Ostrom, a professor at Yale, discovered the carnivorous dinosaur Deinonychus and quickly concluded that its hunting adaptations were suited to an active, agile, and even warm-blooded predator (UCMP Berkeley). He was the first to articulate this view but, rather than become a crusader for it, he was soon eclipsed by his own twenty-three-year-old undergraduate student, Robert Bakker. Now his own professor was providing the impetus for him to share his own perspective, and he did so with zeal. Bakker wrote a paper entitled "The Superiority of Dinosaurs", published in Discovery magazine, which raised the question of how, if dinosaurs had been such failures, they had dominated the earth for so long and forced "superior" mammals to eke out a few small niches in their proverbial shadow (Wilford 1986).

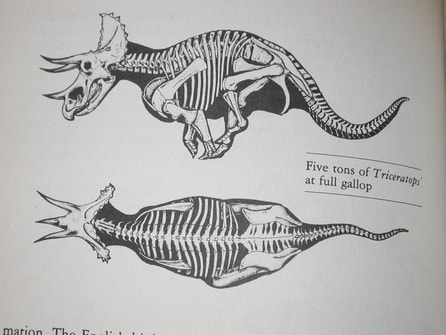

He included illustrations of dinosaurs running at 40 miles per hour. He has said, "People don't compare dinosaurs to other critters. Take the classic orthodox statement, 'Triceratops couldn't run fast.' Why? 'Its legs weren't strong enough.' Compared to what? Rhinos, hippos, elephants are the biggest animals on the surface of the planet now. Giant tortoises are the biggest terrestrial reptile we’ve got. What is a Triceratops more like – a white rhino or a giant tortoise? It’s more like a super-rhino… Pound for pound, the Triceratops has longer and much thicker legs than a white rhino... [E]volution doesn't overbuild more strength than needed. Animals run as fast as the legs they're given" (Lindner 1992).

This paper did not create a stir in the global scientific community, but it did raise the ire of some of his orthodox Yale professors. They could not have known that it marked the beginning of what came to be known as the dinosaur renaissance. Like Darwin, his impact on science began subtly and was largely overlooked for a time.

Though he has remained vague about this spiritual side, Bakker evidently sees it as corroboratory to his scientific side. In responding to critics who are skeptical that much can be learned about long-extinct organisms and ecosystems by studying their fossils, he has written that "these views are wrongheaded. The Book of Job – oldest in the Bible – admonishes, 'Speak to the Earth and it will teach thee.' If we look and listen carefully, the record of the rocks can unlock the richly textured story of the dinosaurs and their ways" (Bakker 1986).

In this vein, he visualizes long-dead fossils as living, breathing dinosaurs. He has remarked, "I want to be the Bob DeNiro of the Jurassic. You know DeNiro is a method actor. When he's going to play the part of a bus driver he wants to feel like a bus driver. If I am studying Camptosaurus I want to feel like Camptosaurus. Which has required 20 years of work. I can kind of feel like Camptosaurus, sniff the ground and think, 'It's too wet here. Too swampy I don't want to go there. Oh dry forest! I want to go there.'" (Prehistoric Planet) He has even written a novel, Raptor Red, which describes the Cretaceous period from the perspective of a Utahraptor (Bakker 1995). With this attitude and perspective he has been able to notice details in the fossil record that others had long overlooked.

Therefore, his scientific side underwent as much or more scrutiny than the spiritual one. He became skeptical of traditional dinosaur portrayals from the age of ten, when he read a 1955 Life magazine article called "The World We Live In" and had a moment similar to "Saul's conversion on the road to Damascus" (Lindner 1992) He continued to be skeptical of some of the conventional wisdom he learned as an undergrad at Yale. The prevailing view, as mentioned, was that dinosaurs were evolutionary failures that had been supplanted by superior mammalian species. Thomas Henry Huxley, "Darwin’s Bulldog", had compared the early bird Archaeopteryx with small therapod dinosaurs like Compsognathus in the late 1860s and concluded that dinosaurs evolved from birds rather than other reptiles (Huxley 1868), but gained little support for this view.

In 1964 John Ostrom, a professor at Yale, discovered the carnivorous dinosaur Deinonychus and quickly concluded that its hunting adaptations were suited to an active, agile, and even warm-blooded predator (UCMP Berkeley). He was the first to articulate this view but, rather than become a crusader for it, he was soon eclipsed by his own twenty-three-year-old undergraduate student, Robert Bakker. Now his own professor was providing the impetus for him to share his own perspective, and he did so with zeal. Bakker wrote a paper entitled "The Superiority of Dinosaurs", published in Discovery magazine, which raised the question of how, if dinosaurs had been such failures, they had dominated the earth for so long and forced "superior" mammals to eke out a few small niches in their proverbial shadow (Wilford 1986).

He included illustrations of dinosaurs running at 40 miles per hour. He has said, "People don't compare dinosaurs to other critters. Take the classic orthodox statement, 'Triceratops couldn't run fast.' Why? 'Its legs weren't strong enough.' Compared to what? Rhinos, hippos, elephants are the biggest animals on the surface of the planet now. Giant tortoises are the biggest terrestrial reptile we’ve got. What is a Triceratops more like – a white rhino or a giant tortoise? It’s more like a super-rhino… Pound for pound, the Triceratops has longer and much thicker legs than a white rhino... [E]volution doesn't overbuild more strength than needed. Animals run as fast as the legs they're given" (Lindner 1992).

This paper did not create a stir in the global scientific community, but it did raise the ire of some of his orthodox Yale professors. They could not have known that it marked the beginning of what came to be known as the dinosaur renaissance. Like Darwin, his impact on science began subtly and was largely overlooked for a time.

The Renaissance Gains Momentum

In 1974 John Ostrom, still being inspired by his discovery of Deinonychus, published a paper called "Archaeopteryx and the Origin of Flight" which resurrected Huxley’s theory of over a century earlier that dinosaurs were descended from birds. Like Huxley, he pointed out the similarities between Archaeopteryx and small therapod dinosaurs, claiming that "[t]he osteology… in virtually every detail, is indistinguishable…" In the intervening time between Huxley and Ostrom, other scientists had supported and defended the theory - and his paper gave an overview of some of these - but still it had never become popular (Ostrom 1974). Because of Ostrom’s paper it was now about to go mainstream - but once again it was his former student and continuing collaborator, Robert Bakker, who took over and caused it to do so.

The next year, in April, Bakker published an article entitled "The Dinosaur Renaissance" in Scientific American, coining the term that would come to describe his revolution against orthodoxy. It reiterated the warm-blooded theory of his undergrad paper but now also proposed that dinosaurs were the ancestors of birds. This paper gained more widespread attention than his first and marked the unstoppable momentum of his ideas. As he developed and refined them he came up with additional theories. For example, he believed that dinosaurs had directly influenced the evolution of flowering plants and that disease, rather than the asteroid impact at the end of the Cretaceous, had been responsible for their extinction.

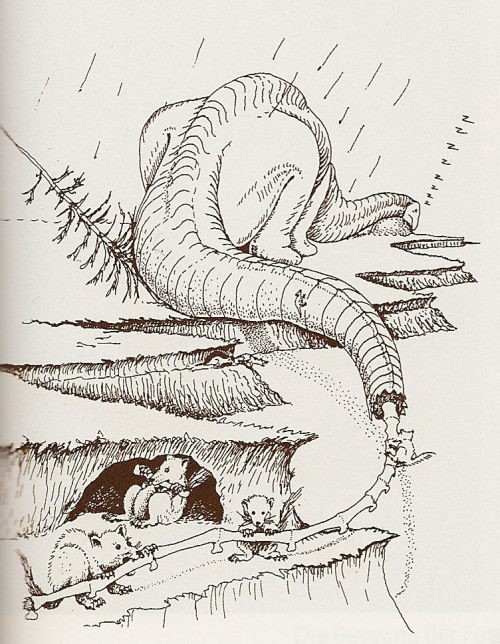

By 1986 Bakker's ideas were sufficiently developed for him to publish his seminal work, a book called The Dinosaur Heresies: New Theories Unlocking the Mystery of the Dinosaurs and Their Extinction, which elaborated on his current theories, addressed criticisms that had arisen, and included several of his own illustrations (Figure 1, Figure 2). Though lacking the impact and controversy of Darwin’s On the Origin of Species, it paralleled that earlier book in its role of bringing theories and ideas out of scientific obscurity and into the public eye. However, unlike Darwin’s book – which marked the beginning of a scientific revolution – Bakker’s marked the climax of one. Despite the opposition to his theories, he had by this time gained substantial support.

The next year, in April, Bakker published an article entitled "The Dinosaur Renaissance" in Scientific American, coining the term that would come to describe his revolution against orthodoxy. It reiterated the warm-blooded theory of his undergrad paper but now also proposed that dinosaurs were the ancestors of birds. This paper gained more widespread attention than his first and marked the unstoppable momentum of his ideas. As he developed and refined them he came up with additional theories. For example, he believed that dinosaurs had directly influenced the evolution of flowering plants and that disease, rather than the asteroid impact at the end of the Cretaceous, had been responsible for their extinction.

By 1986 Bakker's ideas were sufficiently developed for him to publish his seminal work, a book called The Dinosaur Heresies: New Theories Unlocking the Mystery of the Dinosaurs and Their Extinction, which elaborated on his current theories, addressed criticisms that had arisen, and included several of his own illustrations (Figure 1, Figure 2). Though lacking the impact and controversy of Darwin’s On the Origin of Species, it paralleled that earlier book in its role of bringing theories and ideas out of scientific obscurity and into the public eye. However, unlike Darwin’s book – which marked the beginning of a scientific revolution – Bakker’s marked the climax of one. Despite the opposition to his theories, he had by this time gained substantial support.

The science reviewer for the New York Times wrote, “On some points Mr. Bakker no longer finds himself the lonely heretic. Most paleontologists now believe that birds did indeed descend from dinosaurs, though they are not yet prepared to accede to Mr. Bakker's proposal that dinosaurs be regrouped with birds in the class Aves. Nor is he far from the mainstream on the question of dinosaurian extinction. Like many paleontologists, he disputes theories ascribing the mass extinction to a sudden catastrophe caused by an asteroid or comet; he suspects migrations of alien dinosaurs and other animals brought both new diseases and new competition, dooming the giant reptiles” (Wilford 1986).

By this point Bakker had developed several arguments in favor of endothermic dinosaurs. Again he insisted that they must have had quick metabolisms to compete with and eclipse mammals for so long, and as an example he compared them to Komodo dragons – widely considered to be among the most powerful and successful modern reptiles – which are confined to a few islands because they would be outdone by mammals on the mainland. Yet this time he also paid close attention to the dinosaurs' physiology. Besides the obvious anatomical similarities with birds and differences from reptiles, he argued that the rate of growth observed in their bones, the size of organs indicated by their body cavities, and the gaits recorded by their footprints all required a warm-blooded paradigm.

Furthermore, such large cold-blooded animals would have barely been able to function in the climates believed to have existed during the Mesozoic. As a corollary to this he disputed the long-held idea that herbivorous dinosaurs, especially the “duck-billed” varieties, lived in swamps. He pointed out that neither duckbill feet nor tails were even remotely adapted for swimming. His other theories of dinosaur interactions leading to the evolution of flowers and non-catastrophic extinction were also touched on at some length. To support his theories he frequently cited facts that were obvious but had long been deemed unimportant by confirmation bias.

Furthermore, such large cold-blooded animals would have barely been able to function in the climates believed to have existed during the Mesozoic. As a corollary to this he disputed the long-held idea that herbivorous dinosaurs, especially the “duck-billed” varieties, lived in swamps. He pointed out that neither duckbill feet nor tails were even remotely adapted for swimming. His other theories of dinosaur interactions leading to the evolution of flowers and non-catastrophic extinction were also touched on at some length. To support his theories he frequently cited facts that were obvious but had long been deemed unimportant by confirmation bias.

A Paradigm Shifted

Within a few years the widespread acceptance of many of Bakker’s views became obvious. His work was used heavily by author Michael Crichton in the bestselling 1990 novel Jurassic Park which, despite its science fiction elements, aimed to keep its portrayal of dinosaurs as accurate as possible. One of the main protagonists, Dr. Alan Grant, is portrayed as a proponent of Bakker's theories and the other leading figure in the dinosaur renaissance (Crichton 1990). The 1993 blockbuster film version of the novel, though containing many anatomical inaccuracies in the dinosaurs, had perhaps the most widespread cultural impact to date in revising commonly held views about them. The creatures in the movie were fast, intelligent, and a serious threat to the "superior" mammalian tourists. Other portrayals in popular media, more numerous now that interest in dinosaurs had been revitalized, followed a similar vein.

The dinosaur renaissance had come to a successful conclusion. While still giving occasional interviews and presentations, Bakker continues to work as a paleontologist and serves as the Curator of Paleontology for the Houston Museum of Natural Science. Like Darwin following the publication of On the Origin of Species, he continues to develop new theories and fine-tune his old ones, but nothing has matched the impact of his initial contributions.

The dinosaur renaissance had come to a successful conclusion. While still giving occasional interviews and presentations, Bakker continues to work as a paleontologist and serves as the Curator of Paleontology for the Houston Museum of Natural Science. Like Darwin following the publication of On the Origin of Species, he continues to develop new theories and fine-tune his old ones, but nothing has matched the impact of his initial contributions.

Conclusion

Bakker's vision of dinosaurs is more or less the one that prevails among both scientists and lay people today, and for good reason. As more evidence is accumulated much of it continues to vindicate his once "heretical" claims. Among revolutionary scientists, such as Darwin and others, he holds the rare luck and distinction of seeing most of his views accepted within his own lifetime. Only time will tell whether the scientific community as a whole has learned a permanent lesson from this experience, and whether it will be applied to other fields of study. Scientists are still only human.

More continues to be learned, and theories about how dinosaurs evolved and lived continue to be revised and re-evaluated with additional evidence every year (Godefroit et al., 2013). As in nearly all situations in science, the evidence is still not entirely black and white. Evidence is occasionally found that supports older views, indicating that dinosaurs may have been cold-blooded after all or that they were in some ways more similar to reptiles than birds (Ruben et al., 2003). The status quo has shifted, but the debate itself is far from over.

Given his mindset of independent thinking, Bakker himself probably appreciates this even when his theories are the ones being challenged. When asked if he would like to see them be universally accepted, he responded, "God, no. Then I'd be the new orthodoxy! The battle is mostly won. The Golden Book of Dinosaurs – the most widely distributed book on dinosaurs - is totally different than the one I grew up with. Brontosaur is out of the swamps; it's no longer green; dinosaurs are evolving into birds… That means a hundred million kids worldwide have been correctly informed. The genie is out of the bottle and will never go back in. And if some of my stuffy colleagues refuse to catch up with The Golden Book, that's their prerogative" (Lindner 1992).

More continues to be learned, and theories about how dinosaurs evolved and lived continue to be revised and re-evaluated with additional evidence every year (Godefroit et al., 2013). As in nearly all situations in science, the evidence is still not entirely black and white. Evidence is occasionally found that supports older views, indicating that dinosaurs may have been cold-blooded after all or that they were in some ways more similar to reptiles than birds (Ruben et al., 2003). The status quo has shifted, but the debate itself is far from over.

Given his mindset of independent thinking, Bakker himself probably appreciates this even when his theories are the ones being challenged. When asked if he would like to see them be universally accepted, he responded, "God, no. Then I'd be the new orthodoxy! The battle is mostly won. The Golden Book of Dinosaurs – the most widely distributed book on dinosaurs - is totally different than the one I grew up with. Brontosaur is out of the swamps; it's no longer green; dinosaurs are evolving into birds… That means a hundred million kids worldwide have been correctly informed. The genie is out of the bottle and will never go back in. And if some of my stuffy colleagues refuse to catch up with The Golden Book, that's their prerogative" (Lindner 1992).

References

Bakker, R. T., 1986, The Dinosaur Heresies: New Theories Unlocking the Mystery of the Dinosaurs and Their Extinction, Citadel Press

Bakker, R. T., 1995, Raptor Red, Bantam Books

Ch’ng, K. S., Zaharim, N. M., Confirmation Bias and Convergence of Beliefs: an Agent-Based Model Approach, Malaysian Journal of Economic Studies 47 (1): 19-31, 2010

Crichton, J. M., 1990, Jurassic Park, Alfred A. Knopf, Inc.

Godefroit, P., Cau, A., Dong-Yu, H., Escuillié, F., Wenhao, W., Dyke, G., 2013, A Jurassic Avialan Dinosaur from China Resolves the Early Phylogenetic History of Birds, Nature

Huxley, T. H., 1868, On the Animals Which are Most Nearly Intermediate Between Birds and Reptiles, The Annals and Magazine of Natural History 66-75

Lindner, V., March 1992, Robert Bakker Interview, Omni 14 (6): 64-69

Ostrom, J. H., March 1974, Archaeopteryx and the Origin of Flight, The Quarterly Review of Biology 27-47

Owen, R., 1842, Report on British Fossil Reptiles, Report of the Eleventh Meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science 60-203

Pearce, C. and Good, M., November 1992, The Gospel According to Robert, On Air

Prehistoric Planet, Robert T. Bakker: Legend of Paleontology, http://www.prehistoricplanet.com/features/index.php?id=26

Ruben, J. A., Jones, T. D., and Geist, N. R., 2003, Respiratory and Reproductive Paleophysiology of Dinosaurs and Early Birds, Invited Perspectives in Physiological and Biochemical Zoology 141-164

UCMP Berkeley, Dromaesauridae, http://www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/diapsids/saurischia/dromaeosauridae.html

Wilford, J. N., October 26, 1986, Smile When You Call Them Lizards, New York Times Book Review

Read more of my essays here.

Bakker, R. T., 1995, Raptor Red, Bantam Books

Ch’ng, K. S., Zaharim, N. M., Confirmation Bias and Convergence of Beliefs: an Agent-Based Model Approach, Malaysian Journal of Economic Studies 47 (1): 19-31, 2010

Crichton, J. M., 1990, Jurassic Park, Alfred A. Knopf, Inc.

Godefroit, P., Cau, A., Dong-Yu, H., Escuillié, F., Wenhao, W., Dyke, G., 2013, A Jurassic Avialan Dinosaur from China Resolves the Early Phylogenetic History of Birds, Nature

Huxley, T. H., 1868, On the Animals Which are Most Nearly Intermediate Between Birds and Reptiles, The Annals and Magazine of Natural History 66-75

Lindner, V., March 1992, Robert Bakker Interview, Omni 14 (6): 64-69

Ostrom, J. H., March 1974, Archaeopteryx and the Origin of Flight, The Quarterly Review of Biology 27-47

Owen, R., 1842, Report on British Fossil Reptiles, Report of the Eleventh Meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science 60-203

Pearce, C. and Good, M., November 1992, The Gospel According to Robert, On Air

Prehistoric Planet, Robert T. Bakker: Legend of Paleontology, http://www.prehistoricplanet.com/features/index.php?id=26

Ruben, J. A., Jones, T. D., and Geist, N. R., 2003, Respiratory and Reproductive Paleophysiology of Dinosaurs and Early Birds, Invited Perspectives in Physiological and Biochemical Zoology 141-164

UCMP Berkeley, Dromaesauridae, http://www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/diapsids/saurischia/dromaeosauridae.html

Wilford, J. N., October 26, 1986, Smile When You Call Them Lizards, New York Times Book Review

Read more of my essays here.