My pedagogical research project for English 6820.

Creating a Pedagogy of Critical Thinking and Student Agency

(Even as a Lowly Graduate Instructor)

Pedagogy, for those of you who don't know, is just a fancy word for "teaching methods". It's not a complicated concept but it does encompass a massive range of possibilities that probably hold little or no interest for you if you aren't a teacher. Still with me? Great.

Fall 2020 was my first semester as a graduate instructor of English 1010, "Introduction to Writing: Academic Prose", at Utah State University. Like most graduate instructors, I came in with next to no teaching experience, felt totally overwhelmed and suffered from a huge case of imposter syndrome. Many of the things I read and discussed in graduate school seemed to say, "This is how teachers have traditionally taught, and here's why that's all wrong and we need to do it a better way." Much of it challenged my own assumptions and expectations about what writing and composition were supposed to look like. At times it felt as if I was personally expected to totally overhaul the American education system that I just entered - a daunting task. I do like to criticize things, though, so I guess that gives me an advantage.

As I taught various English 1010 assignments to fit various Learning Outcomes, I find myself gravitating over and over to the outcome of critical thinking, which in my mind always seemed to loom over the others in importance. USU defines this objective like so:

Fall 2020 was my first semester as a graduate instructor of English 1010, "Introduction to Writing: Academic Prose", at Utah State University. Like most graduate instructors, I came in with next to no teaching experience, felt totally overwhelmed and suffered from a huge case of imposter syndrome. Many of the things I read and discussed in graduate school seemed to say, "This is how teachers have traditionally taught, and here's why that's all wrong and we need to do it a better way." Much of it challenged my own assumptions and expectations about what writing and composition were supposed to look like. At times it felt as if I was personally expected to totally overhaul the American education system that I just entered - a daunting task. I do like to criticize things, though, so I guess that gives me an advantage.

As I taught various English 1010 assignments to fit various Learning Outcomes, I find myself gravitating over and over to the outcome of critical thinking, which in my mind always seemed to loom over the others in importance. USU defines this objective like so:

Writers practice critical thinking when they analyze, synthesize, interpret, and evaluate ideas, information, situations, and texts. |

I took AP English in high school and thus skipped English 1010, but an introductory philosophy course I took my first semester was very impactful in teaching me how to think more than what to think. We evaluated arguments from all the great ancient philsophers that seemed equally convincing even though they openly contradicted each other, and I had to really consider what I believed and why. As a teacher in a different branch of the humanities, I want to replicate that impact on my students to the fullest extent possible. I want to prepare them to change their own lives and the world. I believe many of the problems in our nation today stem from people constructing echo chambers around themselves, acting as slaves to confirmation bias, and believing everything they read on the internet. Constructive dialogue and respectful disagreement between people of goodwill have almost become lost arts. Admittedly I'm part of the problem sometimes, but maybe it's too late for me. Maybe my students still have a chance to be better if I train them before they're too set in their ways.

The American political sphere especially has devolved into a mud-slinging competition that gets worse every four years. I've even brought it up in class multiple times (without pushing any particular viewpoints) as an example of what not to do. Everyone from across the political spectrum seemed to agree that the September 2020 presidential debate was just embarrassing and depressing to watch. One of my students said he watched for twenty minutes before he had to turn it off. The only good thing to come out of it was "Weird Al" Yankovic's songified version, "WE'RE ALL DOOMED", which accurately captured most Americans' feelings. I encouraged my students to look it up on their own time because I couldn't quite justify showing it in class.

The American political sphere especially has devolved into a mud-slinging competition that gets worse every four years. I've even brought it up in class multiple times (without pushing any particular viewpoints) as an example of what not to do. Everyone from across the political spectrum seemed to agree that the September 2020 presidential debate was just embarrassing and depressing to watch. One of my students said he watched for twenty minutes before he had to turn it off. The only good thing to come out of it was "Weird Al" Yankovic's songified version, "WE'RE ALL DOOMED", which accurately captured most Americans' feelings. I encouraged my students to look it up on their own time because I couldn't quite justify showing it in class.

I also want my students to like and trust me, so I don't want to come across as one of those liberal professors their parents probably warned them about trying to shove my beliefs down their throats. That means no political bias in my lessons even when I'd really like to point out that Trump is objectively a jackass.

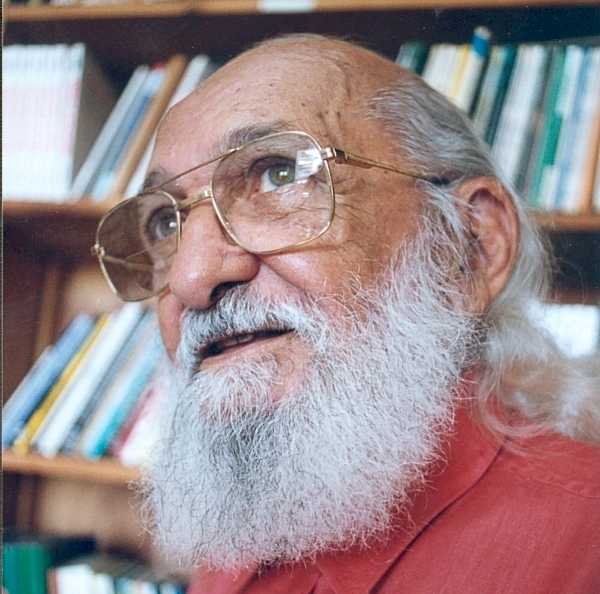

But my second day as a teacher, after the syllabus and get-to-know-you stuff were out of the way, was extremely awkward and left me thinking that I would need to fake my own death because it was too late to quit. A big reason was that multiple times I asked my students a direct question and they all just stared at me - or at least, some of them stared at me while I couldn't tell about the majority because they had their cameras turned off. This was over Zoom, during the pandemic, which I'm sure partially accounted for the awkwardness. But I think another factor was that these students, most of them in their first semester of college, had come expecting me to just talk at them for fifty minutes. That's not something I could do even if I wanted to, but it's probably what they experienced in high school and probably the average American's idea of what formal education looks like even in this day and age. As we read in my practicum, Paulo Freire writes,

But my second day as a teacher, after the syllabus and get-to-know-you stuff were out of the way, was extremely awkward and left me thinking that I would need to fake my own death because it was too late to quit. A big reason was that multiple times I asked my students a direct question and they all just stared at me - or at least, some of them stared at me while I couldn't tell about the majority because they had their cameras turned off. This was over Zoom, during the pandemic, which I'm sure partially accounted for the awkwardness. But I think another factor was that these students, most of them in their first semester of college, had come expecting me to just talk at them for fifty minutes. That's not something I could do even if I wanted to, but it's probably what they experienced in high school and probably the average American's idea of what formal education looks like even in this day and age. As we read in my practicum, Paulo Freire writes,

Education thus becomes an act of depositing, in which the students are the depositories and the teacher is the depositor. Instead of communicating, the teacher issues communiques and makes deposits which the students patiently receive, memorize, and repeat. This is the 'banking' concept of education, in which the scope of action allowed tothe students extends only as far as receiving, filing, and storing the deposits. They do, it is true, have the opportunity to become collectors or cataloguers of the things they store. But in the last analysis, it is the people themselves who are filed away through the lack of creativity, transformation, and knowledge in this (at best) misguided system. For apart from inquiry, apart from the praxis, individuals cannot be truly human. Knowledge emerges only through invention and reinvention, through the restless, impatient continuing, hopeful inquiry human beings pursue in the world, with the world, and with each other." (Freire) |

The first week, my students didn't come mentally prepared for the discussion-based atmosphere that I had taken for granted. I made an announcement explaining it to them, and with trial and error and advice from colleagues, things got much better. For example, I asked most of my questions in the Zoom chat instead of out loud, and when I did, a majority of students responded. I then read through their responses out loud, affirming and/or expanding on them where I could, and sometimes asking follow-up questions to individual students. Education in this way became truly a collaborative effort. I could not predict in advance what my students would say, so I was, in part, giving them power or agency to direct part of the lesson while I improvised and adapted accordingly. In practice this was much easier than having all my words planned in advance. And in the process of responding to their responses, as trite as it sounds, I feel that I learned things too.

Of course critical thinking, by design, is already built into the curriculum and each of the major assignments. My question is how to bring it out to my students to its fullest potential and not just pay lip service to the idea. I'm very focused on equipping them to succeed not just in this class, but in future classes and eventually the real world. Maybe it's because I deeply care about them as individuals or maybe it's just because I want to feel like what I do matters. It's probably a little of both.

Of course critical thinking, by design, is already built into the curriculum and each of the major assignments. My question is how to bring it out to my students to its fullest potential and not just pay lip service to the idea. I'm very focused on equipping them to succeed not just in this class, but in future classes and eventually the real world. Maybe it's because I deeply care about them as individuals or maybe it's just because I want to feel like what I do matters. It's probably a little of both.

What is Student Agency?

I mentioned that I gave students agency to direct part of the lesson, and I think this idea is at the heart of critical thinking. In the past I've always just thought of agency as a person's intrinsic ability to think and move on their own instead of being controlled by God or some external force like a puppet. I thought of it almost entirely as a philosophical or theological concept. This semester, though, I unexpectedly learned that it's a subject of intense academic study and debate, and far more complex than I could have imagined. I don't pretend to understand much of it yet - most of the academic jargon goes way over my head, so I just skim and try to pick up the key points.

From what I've pieced together, though, it seems that agency is not as self-contained as I would have thought. To some degree it's inseparable from the agency of others that one interacts with, and may even be disseminated throughout an assemblage of external human and non-human factors that one finds oneself in. (I've been very drawn to this assemblage concept because it reminds me of chaos theory, which I know about from the novel Jurassic Park, which discusses it in much greater detail than the movie version.) For example, Carolyn R. Miller has written:

I suggest... that we think of agency as the kinetic energy of rhetorical performance. The Greek root of energy is ergon, deed or work, and energeia is the deed in the doing, action itself. In invoking the distinction that physics makes between potential and kinetic energy, I'm comparing agency not to the energy of a stone sitting at the top of the cliff but rather to the energy it has as it falls, the energy of motion.... |

Miller argues in her paper that this relationship between live entities is essential, and that AutoSpeech-Easy, a hypothetical software for automated evaluation of public speaking performance, would not be able to produce the same kinetic energy or agency in the speaker. Such a product sounds less absurd now than it probably did when she wrote about it in 2007. She certainly didn't anticipate how much education would lean on technology during a massive pandemic, and it's interesting to think about how the Zoom situation may complicate this attribution of agency. I felt since the first day of teaching that the physical separation of my students from me and the classroom made things more difficult, even when I couldn't put my finger on why. I think Miller is onto something and that the kinetic energy is weakened by the distance between the parties involved. Even when my students turned their cameras on and even when they spoke, I knew they weren't in the room with me and they knew I wasn't in the room with them, and that had a psychological impact. I believe the same impact separated them from each other as well - as much as I encouraged them to talk among themselves before class and take advantage of one of their rare opportunities for socialization, they wouldn't do it.

Marilyn M. Cooper similarly opines that "though the world changes in response to individual action, agents are very often not aware of their intentions, they do not directly cause changes, and the choices they make are not free from influence from their inheritance, past experiences, or their surround. I argue that agency is an emergent property of embodied individuals." (Cooper 421) Using a speech by Barack Obama during his 2008 presidential campaign as an example, she explains:

Marilyn M. Cooper similarly opines that "though the world changes in response to individual action, agents are very often not aware of their intentions, they do not directly cause changes, and the choices they make are not free from influence from their inheritance, past experiences, or their surround. I argue that agency is an emergent property of embodied individuals." (Cooper 421) Using a speech by Barack Obama during his 2008 presidential campaign as an example, she explains:

His choice of how to respond this time, to articulate what he believed and wanted to say about race at this moment, could, like his earlier choice, be traced to a 'larger narrative,' one he had been living and reflecting on and writing for many years. Like all responses, it emerged from the ongoing process of his becoming the person he is, as he responded to the world he encountered and the history he studied and as neural populations interacted within the complex system of his brain, creating emotions, intentions, moods, dispositions, meanings, memories, goals, and narratives.... |

Cooper makes an interesting point that has been echoed by other scholars. My agency is limited by my life up to this point. Everything from the way my parents raised me, to the training I received during Orientation the week before school and the practicum throughout the semester, to the possibilities and limitations of the Zoom technology, shaped the assemblage I was in and consequently the options available to me as a teacher. I didn't have truly unlimited freedom to do whatever I want because some options weren't available or would never have occurred to me with the knowledge and experiences that I had. That's all right, though, because with truly unlimited freedom I would have been a blank slate with no guidance and thus incapable of acting anyway. All options would be available in theory but I wouldn't have the knowledge or experience to recognize them. When some options are made plain to me, others are inevitably closed off, and that's just the way it is.

Her other point, of course, reaffirms Miller's. It seems that my students, whether they realized it or not, came in perceiving me as the sole source of agency, without an understanding of their proper role in their own education. They expected that as the teacher I would just sit there and run the class on my own, depositing information into their brains, and didn't recognize that I could only send out "perturbations" to which they, in turn, needed to respond - which would remain true even if I were an accomplished orator like Obama and even if I weren't going for such a discussion-based class. The fact that I'm not and I am, respectively, only complicates it even further. In future classes I want to create an infinite feedback loop of kinetic energy where they and I feed off each other and all are edified, not just in knowledge but in skills to process and apply that and any future knowledge.

(As far as the definition of agency goes, I don't stray far beyond these two scholars, though others have written their own, sometimes contradictory thoughts on the subject. I certainly don't buy into the argument that agency isn't even real, but a necessary fantasy - and even if I did, how would that change my teaching practices? I think it would just depress me out of teaching at all because nothing really matters.)

Of course, an institutional shift away from the banking model has been ongoing in many areas for decades, and I'm hardly a pioneer in that regard. I was quite accustomed to discussion-based classes by the time I finished my Bachelor's degree in English. But that shift is slow and inconsistent and hasn't fully permeated the public consciousness, or even academia itself. In a study of student evaluations of teaching (SETs) - the feedback that students typically provide at the end of the semester - Brian Ray et al. found that

Her other point, of course, reaffirms Miller's. It seems that my students, whether they realized it or not, came in perceiving me as the sole source of agency, without an understanding of their proper role in their own education. They expected that as the teacher I would just sit there and run the class on my own, depositing information into their brains, and didn't recognize that I could only send out "perturbations" to which they, in turn, needed to respond - which would remain true even if I were an accomplished orator like Obama and even if I weren't going for such a discussion-based class. The fact that I'm not and I am, respectively, only complicates it even further. In future classes I want to create an infinite feedback loop of kinetic energy where they and I feed off each other and all are edified, not just in knowledge but in skills to process and apply that and any future knowledge.

(As far as the definition of agency goes, I don't stray far beyond these two scholars, though others have written their own, sometimes contradictory thoughts on the subject. I certainly don't buy into the argument that agency isn't even real, but a necessary fantasy - and even if I did, how would that change my teaching practices? I think it would just depress me out of teaching at all because nothing really matters.)

Of course, an institutional shift away from the banking model has been ongoing in many areas for decades, and I'm hardly a pioneer in that regard. I was quite accustomed to discussion-based classes by the time I finished my Bachelor's degree in English. But that shift is slow and inconsistent and hasn't fully permeated the public consciousness, or even academia itself. In a study of student evaluations of teaching (SETs) - the feedback that students typically provide at the end of the semester - Brian Ray et al. found that

A large number of the nearly 1,100 questions we collected focus attention directly on the instructors and situate them as solely responsible for several aspects of the course’s success. Although an instructor plays an undeniable role in shaping course policies, structuring class sessions, and interacting with students, we found ourselves questioning whether most SETs truly reflect the dispersed agentive structures in our classrooms. In fact, the SET forms we analyzed largely promote the single agent model of instruction typical of lecture-style classes that rely on an outdated notion of humanist agency. This model situates control and agency for learning primarily with the instructor and therefore reinforces the notion that the instructor - not the student - is responsible for student success. Such a stance does justice to neither teachers nor students." (Ray et al. 43-44) |

They also report that students hold female teachers to a higher standard (Ray et al. 42) and give higher ratings to more physically attractive teachers (Ray et al. 43). This makes me wonder, is my career screwed because I'm not physically attractive enough? Maybe it's a blessing in diguise that I broadcast my class from campus and had to wear a mask.

Even at the university level, we sometimes say one thing but send a different message. Does the English department of Utah State University, for example, really believe the extent of student agency and responsibility for their own learning, and act accordingly? It makes me nervous because if my students still hold mistaken assumptions about how the classroom is supposed to work, they could evaluate me less favorably for not conforming to that. They could be upset that I tried to elicit so many contributions from them to the classroom assemblage instead of just lecturing them. I think most of them like me, but still. To my knowledge, the end-of-semester evaluations that will be used to judge me have changed little if at all from when I started college almost a decade ago. If we know these things are broken, why haven't we fixed them? I say "we", but I just became a teacher, so none of this is actually my fault.

Even at the university level, we sometimes say one thing but send a different message. Does the English department of Utah State University, for example, really believe the extent of student agency and responsibility for their own learning, and act accordingly? It makes me nervous because if my students still hold mistaken assumptions about how the classroom is supposed to work, they could evaluate me less favorably for not conforming to that. They could be upset that I tried to elicit so many contributions from them to the classroom assemblage instead of just lecturing them. I think most of them like me, but still. To my knowledge, the end-of-semester evaluations that will be used to judge me have changed little if at all from when I started college almost a decade ago. If we know these things are broken, why haven't we fixed them? I say "we", but I just became a teacher, so none of this is actually my fault.

Giving Students Ownership of Their Education

Sometimes "teaching students how to think" is just that - essentially saying, "This is how to think." There's obviously a certain irony to it, but the information should empower them nonetheless. When we discussed the banking model in our practicum, my colleague Greyson Gurley raised the devil's advocate question of whether it's always a negative thing. She argued that sometimes you do just need to give people information, like when you teach kids how to tie their shoes. I think she's right. For example, in one lesson I showed my students this video on the straw man logical fallacy, wherein one misrepresents another's argument to make it easier to refute.

So in this instance I deposited some information, or rather called on someone more articulate and charismatic to do it for me, but once the students know how straw men work they can apply this logic in future scenarios. Because they know how to think about these things, in the future they will be able to evaluate the reliability of arguments they may have never seen before. They'll be on Facebook, see someone sarcastically mocking a certain political position, and think "Wait a minute, that's not actually what [insert political demographic here] believe." Then they'll give some thought to what the actual position is and accept, reject or modify it on its own terms.

In another lesson I shared this video about confirmation bias, the hard-wired human tendency to seek out information that supports what one already believes and downplay or avoid information that doesn't. (My students liked watching videos, and I was happy to oblige them.)

In another lesson I shared this video about confirmation bias, the hard-wired human tendency to seek out information that supports what one already believes and downplay or avoid information that doesn't. (My students liked watching videos, and I was happy to oblige them.)

Learning about confirmation bias was one of my most life-changing experiences, and I hope it was for them as well. I recognized it in myself and made a conscious effort to overcome it, to stop being afraid of sources that challenged my views. Confirmation bias is one of the biggest causes for the political divide in this country. I mentioned to my students that the people who buy pro-conservative or pro-liberal books are, by and large, already conservatives or liberals, respectively. They aren't seeking out other viewpoints, they're seeking to convince themselves that theirs are already correct. If people as a whole recognized and tried to overcome their confirmation bias, they certainly wouldn't all start to agree with each other on everything, but their views would become more nuanced and less dogmatic, and they wouldn't retreat into echo chambers that skew their perception of the world and lead to the intolerant rhetoric and arguing that we see all over the place. I told my students that I'm not saying they need to change their beliefs, but they should be willing to change their beliefs, because if no conceivable logic or evidence can change their beliefs on a topic then they can't approach it honestly and there's no point in discussing it.

In these two examples, I arguably used the banking model as I deposited some knowledge about reasoning and human psychology, but this knowledge removed barriers that limited the options available to my students without reven realizing it. Logical fallacies and confirmation bias are both constraints on agency if one isn't even aware of them in one's own mind. Sometimes our greatest obstacle to critical thinking is our own minds. Students need to think for themselves, but they also need some material to work with in the first place. They can't produce knowledge out of a vacuum regardless of how intelligent they are. Real life isn't like the movie "Lucy" where you can suddenly read Chinese just because you took a drug that makes you really smart. (Also, the movie's central premise that humans only use ten percent of their brains is nonsense.) So the banking model, like banks themselves, can be a necessary evil.

When attempting to teach broader or more nebulous principles, it was often useful to just facilitate as students brainstormed for themselves. For example, the first item listed under the English 1010 Critical Thinking objective is "Interpret the relationships among language, knowledge, and power". Taking substantial inspiration from a similar activity that I did with my classmates in the practicum, I made a Google Doc with slides labeled "Language", "Knowledge", and "Power", each with a corresponding gif.

In these two examples, I arguably used the banking model as I deposited some knowledge about reasoning and human psychology, but this knowledge removed barriers that limited the options available to my students without reven realizing it. Logical fallacies and confirmation bias are both constraints on agency if one isn't even aware of them in one's own mind. Sometimes our greatest obstacle to critical thinking is our own minds. Students need to think for themselves, but they also need some material to work with in the first place. They can't produce knowledge out of a vacuum regardless of how intelligent they are. Real life isn't like the movie "Lucy" where you can suddenly read Chinese just because you took a drug that makes you really smart. (Also, the movie's central premise that humans only use ten percent of their brains is nonsense.) So the banking model, like banks themselves, can be a necessary evil.

When attempting to teach broader or more nebulous principles, it was often useful to just facilitate as students brainstormed for themselves. For example, the first item listed under the English 1010 Critical Thinking objective is "Interpret the relationships among language, knowledge, and power". Taking substantial inspiration from a similar activity that I did with my classmates in the practicum, I made a Google Doc with slides labeled "Language", "Knowledge", and "Power", each with a corresponding gif.

I then put the students in three breakout groups and had each group work on filling out each slide:

•Definitions: |

As you can see, the slides were very open-ended and not fishing for any specific answer. I wanted to see what my students came up with, which in turn would give me something to build on. One group was confused about what I was looking for and needed more guidance, so perhaps I fell short in that regard, but the activity seemed successful over all. It took up the rest of class and at the beginning of the next class, after making my students look at pictures of my new niece that I added to the Doc because I could, we went through all the slides together and I talked about what they had written. If I had come up with such a breadth and depth of ideas on my own and deposited them via the banking model, it would have been very boring for everyone involved and not required the students to use much brainpower. On the other hand, if I hadn't previously provided the students with background information and been present to oversee the discussion, they would have been lost altogether. I used Google Doc activities a few more times for similar reasons.

A person only familiar with the banking model of education may look at something like this and feel that I'm abrogating my responsibility as a teacher by making the class so dependent on student contributions. I'm still facilitating what goes on in the classroom - it's unlikely that students would be having these conversations or thinking about these things otherwise. I provide a space and the prompts to do so, and feedback to help them along.

A person only familiar with the banking model of education may look at something like this and feel that I'm abrogating my responsibility as a teacher by making the class so dependent on student contributions. I'm still facilitating what goes on in the classroom - it's unlikely that students would be having these conversations or thinking about these things otherwise. I provide a space and the prompts to do so, and feedback to help them along.

How Can I Further Expand Student Agency?

English 1010, as an introductory course, can function as a training ground of sorts as students transition from high school to more advanced classes with a higher degree of agency that might overwhelm them if foisted on them all at once. Theories of agency become easier to comprehend, at least for me, when I move away from the academic jargon and look at putting them into practice. Obviously I have guidelines on what I'm supposed to teach. At times the guidelines give me what I find to be a terrifying amount of freedom in choosing content and planning lessons, but they exist nonetheless and I'm not complaining about that. The number and type of assignments - essays, discussions, Writing Center visits, and the like - is already laid out. In theory I have authority to add to or take away from it, but I don't want to overburden my students or short-change their learning.

Within these guidelines, then, I did what I could to give my students options. I encouraged them to pick topics to write about that they would enjoy, not what they thought I wanted to read. I knew this would help them to see writing as less of a chore even though they were being forced to do it for a grade. (I also made a point of telling them that writing, and school in general, will be a lot more fun if they find a major that's a good fit. I should know - I started as an undergraduate in Wildlife Science.) While obligated to explain the things they couldn't do, I tried to give them a positive view of the things they could do, however limited. Shawna Shapiro et al. explain,

Within these guidelines, then, I did what I could to give my students options. I encouraged them to pick topics to write about that they would enjoy, not what they thought I wanted to read. I knew this would help them to see writing as less of a chore even though they were being forced to do it for a grade. (I also made a point of telling them that writing, and school in general, will be a lot more fun if they find a major that's a good fit. I should know - I started as an undergraduate in Wildlife Science.) While obligated to explain the things they couldn't do, I tried to give them a positive view of the things they could do, however limited. Shawna Shapiro et al. explain,

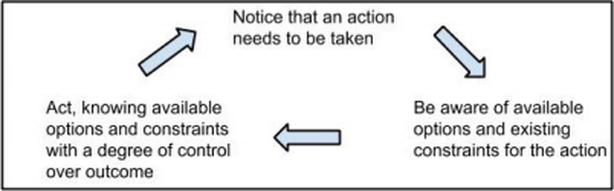

Central to the ability to take action is the idea of 'noticing' that an action needs to be taken and awareness of the available actions one might take.... Once a writer is aware that action needs to be taken, she then must be aware of the range of available actions and the existing constraints on those actions. She must also have the necessary knowledge for informed decisionmaking.... As illustrated in fig. 1, greater awareness leads to greater control. Thus, the framework for writer agency may be summarized as such (see fig. 1)." (Shapiro et al. 33-34) |

As Shapiro et al. point out, options do little good if students aren't aware of them and consequently can't take advantage of them. The authors focus mostly on ESL (English as a Second Language) students, who are usually at more of a disadvantage in this because of language and culture barriers. I haven't had any ESL students yet. Regardless, the same principle applies to all students, who "face the same constraints... such as an instructor’s evaluation criteria, the bounds of an assignment, their own educational histories, or time pressures." (Shapiro et al. 33) As a teacher I must communicate all their options to them as clearly as I can, and of course as a new teacher I'm not very good at that yet. I, too, am still trying to learn and remember how everything works, and my students will bring in assumptions and gaps in their knowledge that I don't even recognize right off. There will be some generalized ones - like the one I mentioned earlier about lecture versus discussion, which are informed by the deficiencies of middle and high school. There will be some more individualized ones that change from student to student, class to class, semester to semester.

I noticed a reluctance from my students to take advantage of options that weren't mandatory. Only one of them visited my office hours one time during the semester, and it was just to reiterate a question she'd asked in an email that I hadn't responded to fast enough. None of them met with the course librarian who was available to help them with their research for one of the essays. I think this is inevitable, seeing as English 1010 is an introductory course that most students are only taking because they have to. It might be like that every semester. On a more somber note, a student disclosed a disability near the beginning of the semester, but never went to the Disability Resource Center to get academic accommodations, and badly failed the class as a result. In addition to recommending the DRC to this student individually three times, I had strongly emphasized it when I went over the syllabus on the first day of class, and shared my personal experience as an undergraduate of losing my scholarship and nearly dropping out because of my depression. I really wanted to be a force for good and leverage my own mistakes to help my students avoid similar ones. My inability to do so is already the greatest disappointment of my fledgling career. But as Cooper notes, I can only send out the perturbation of agency - I can't control how my students choose to respond to it, or not. As depressing as it is, they might just need time to learn some things the hard way.

Students' options can be expanded still further by taking a broader view of what "composition" might entail to begin with. Cynthia L. Selfe noted as early as 2004 (when most of my students were babies!) that in the twenty-first century, focusing only on alphabetic literacy (a.k.a. words) leaves a classroom increasingly out of touch with the real world:

I noticed a reluctance from my students to take advantage of options that weren't mandatory. Only one of them visited my office hours one time during the semester, and it was just to reiterate a question she'd asked in an email that I hadn't responded to fast enough. None of them met with the course librarian who was available to help them with their research for one of the essays. I think this is inevitable, seeing as English 1010 is an introductory course that most students are only taking because they have to. It might be like that every semester. On a more somber note, a student disclosed a disability near the beginning of the semester, but never went to the Disability Resource Center to get academic accommodations, and badly failed the class as a result. In addition to recommending the DRC to this student individually three times, I had strongly emphasized it when I went over the syllabus on the first day of class, and shared my personal experience as an undergraduate of losing my scholarship and nearly dropping out because of my depression. I really wanted to be a force for good and leverage my own mistakes to help my students avoid similar ones. My inability to do so is already the greatest disappointment of my fledgling career. But as Cooper notes, I can only send out the perturbation of agency - I can't control how my students choose to respond to it, or not. As depressing as it is, they might just need time to learn some things the hard way.

Students' options can be expanded still further by taking a broader view of what "composition" might entail to begin with. Cynthia L. Selfe noted as early as 2004 (when most of my students were babies!) that in the twenty-first century, focusing only on alphabetic literacy (a.k.a. words) leaves a classroom increasingly out of touch with the real world:

Global communications, for example - exchanged via increasingly complicated computer networks that stretch across traditional geographic and political borders and that include people from different cultures who speak different languages - increasingly involve texts that depend heavily, even primarily, on visual elements (New London Group). Moreover, with the ongoing expansion of global markets, political systems, and communication networks, such an emphasis is sure to continue, if not increase. |

Selfe's caution became even more relevant when the pandemic forced schools and universities (along with many other sectors) to go almost entirely digital almost overnight. I'm sure that we'll never go all the way back to the "old normal" even when in-person classes resume. Some of the new ways of doing things will be kept, either because they're improvements on the old methods or simply because they offer additional possibilities.

It's appropriate, then, that the last assignment I gave this semester, the Multimodal Remix, requires students to remix their last essay into another format - video, podcast, blog, or whatever creative thing they can come up with - adapting the essay to a new rhetorical communication by adjusting the different modes of communication therein. In the weekly Online Learning that I wrote to introduce it, I used one of the sample essays my students had access to, and walked through what a hypothetical remix looked like. I walked through audience, medium, genre, topic, and purpose, and how each would have to be considered and altered for the new rhetorical situation. I believe giving concrete examples as I explained each one made them easier for students to grasp (and easier for me to grasp, for that matter). Karla Saari Kitalong and Rebecca L. Miner have extolled the potential of such multimodal projects to enhance student agency, concluding that

It's appropriate, then, that the last assignment I gave this semester, the Multimodal Remix, requires students to remix their last essay into another format - video, podcast, blog, or whatever creative thing they can come up with - adapting the essay to a new rhetorical communication by adjusting the different modes of communication therein. In the weekly Online Learning that I wrote to introduce it, I used one of the sample essays my students had access to, and walked through what a hypothetical remix looked like. I walked through audience, medium, genre, topic, and purpose, and how each would have to be considered and altered for the new rhetorical situation. I believe giving concrete examples as I explained each one made them easier for students to grasp (and easier for me to grasp, for that matter). Karla Saari Kitalong and Rebecca L. Miner have extolled the potential of such multimodal projects to enhance student agency, concluding that

by encouraging free invention and fostering creative thinking, instructors release a certain amount of control to the students. This release may make some teachers uneasy; they may, for example, fear that the learning atmosphere in their class lacks seriousness or rigor. Students, too, may struggle with how to channel their new-found control towards the goals of their project or the learning objectives of the course. For perhaps the first time in their lives, they may not know exactly what message the teacher expects them to convey or what precise form that message should take. And yet, the excitement of being free to compose in multiple modalities generates students’ engagement in their own learning, which leads them toward reflectiveness and self-awareness.... [A]s college composition students experiment with multiple modalities, they learn... that it is okay to struggle and beneficial to make changes in response to critiques of their work. They become more comfortable combining modes that were initially uncomfortable; ultimately, the work of rhetorically analyzing and revising their projects generates more precise and potentially more powerful messages that reveal elements of personal agency, especially evident in their reflections." (Kitalong & Miner 53) |

This release doesn't make me uneasy. The less I have to talk and be boring, the better.

I have some experience with a similar project. As an undergraduate in a course called "Unveiling the Anthropocene", I was given a very open-ended final project that only required me to use some kind of art form to communicate the science of climate change to a lay audience. The professor explained that scientists are really bad at communicating with normal people and hoped to empower us to bridge the gap. I ended up collaborating on a Jane Austen video blog parody with one of my classmates, Sarah Gee, because I didn't have any better ideas. My acting and mannerisms are too painful for me to watch but the video was fun to make, at least, and certainly more enjoyable than writing a final paper. More to the point, we had to consider how to communicate our information to an ignorant and potentially skeptical general audience, not a professor.

I have some experience with a similar project. As an undergraduate in a course called "Unveiling the Anthropocene", I was given a very open-ended final project that only required me to use some kind of art form to communicate the science of climate change to a lay audience. The professor explained that scientists are really bad at communicating with normal people and hoped to empower us to bridge the gap. I ended up collaborating on a Jane Austen video blog parody with one of my classmates, Sarah Gee, because I didn't have any better ideas. My acting and mannerisms are too painful for me to watch but the video was fun to make, at least, and certainly more enjoyable than writing a final paper. More to the point, we had to consider how to communicate our information to an ignorant and potentially skeptical general audience, not a professor.

I'm interested to see how much agency my students will exercise in this assignment. I told them they're welcome to be creative and come up with something other than the ideas I listed, but I don't know if any of them will be motivated enough or feel comfortable doing so. I didn't list a bunch of unconventional examples because I'm not that creative myself. The only one I mentioned was a cereal box, which I heard suggested by someone else in my practicum. So I gave my students the leeway, but whatever options are available to them, whichever ideas may occur to them based on their experiences and knowledge, have little to do directly with me. I just hope that, throughout the semester, I've successfully fostered an environment that makes them feel safe exploring those options. This could have a long-term impact on their confidence in filling future assignments and pursuing their career goals for years down the road. I hope they can thrive regardless of what options they find available at any given time.

Unfortunately there are other factors to consider besides critical thinking and agency. The students only have a couple weeks to do this assignment, and I didn't introduce it very far in advance, and the end of the semester is the busiest time already. Students who would otherwise be more creative might opt instead to do something simple just because they don't feel they have the time to explore their options or pull off something elaborate. In the future, I would like to adjust the schedule to give them more time, or at the very least tell them about the final project much earlier so they can have it in the backs of their minds well in advance.

I believe I have, through the guidance provided to me and my own trial and error, really hit upon the truth of Freire's sentiment that "Knowledge emerges only through invention and reinvention, through the restless, impatient continuing, hopeful inquiry human beings pursue in the world, with the world, and with each other." I hope that my students would agree and feel that they've learned a lot despite my shortcomings as a teacher. There is a great deal of work to do - Freire made his critique before my parents were born, yet the fact that we're still reading it implies that we haven't fully addressed the issue, even in the English department at USU. Can I singlehandedly make that happen? I doubt it very much, but I'll do my best. It might be a lot easier without Zoom.

Unfortunately there are other factors to consider besides critical thinking and agency. The students only have a couple weeks to do this assignment, and I didn't introduce it very far in advance, and the end of the semester is the busiest time already. Students who would otherwise be more creative might opt instead to do something simple just because they don't feel they have the time to explore their options or pull off something elaborate. In the future, I would like to adjust the schedule to give them more time, or at the very least tell them about the final project much earlier so they can have it in the backs of their minds well in advance.

I believe I have, through the guidance provided to me and my own trial and error, really hit upon the truth of Freire's sentiment that "Knowledge emerges only through invention and reinvention, through the restless, impatient continuing, hopeful inquiry human beings pursue in the world, with the world, and with each other." I hope that my students would agree and feel that they've learned a lot despite my shortcomings as a teacher. There is a great deal of work to do - Freire made his critique before my parents were born, yet the fact that we're still reading it implies that we haven't fully addressed the issue, even in the English department at USU. Can I singlehandedly make that happen? I doubt it very much, but I'll do my best. It might be a lot easier without Zoom.

Bibliography

Cooper, Marilyn M. “Rhetorical Agency as Emergent and Enacted.” College Composition and Communication, vol. 62, no. 3, 2011, pp. 420–449.

Freire, Paulo. “Chapter 2.” Pedagogy of the Oppressed, by Paulo Freire, Continuum., 1993, pp. 71–86.

Kitalong, Karla Saari, & Rebecca L. Miner. “Multimodal Composition Pedagogy Designed to Enhance Authors’ Personal Agency: Lessons from Non-Academic and Academic Composing Environments.” Computers and Composition, vol. 46, 2017, pp. 39–55., doi:10.1016/j.compcom.2017.09.007.

Miller, Carolyn R. “What Can Automation Tell Us About Agency?” Rhetoric Society Quarterly, vol. 37, no. 2, 2007, pp. 137–157., doi:10.1080/02773940601021197.

Ray, Brian, et al. “Rethinking SETs: Retuning Student Evaluations of Teaching for Student Agency.” Composition Studies, vol. 46, no. 1, 2018, pp. 34–56.

Selfe, Cynthia L. “Toward New Media Texts: Taking Up the Challenges of Visual Literacy.” The St. Martin's Guide to Teaching Writing, by Cheryl Glenn and Melissa A. Goldthwaite, Bedford/St. Martin's, Boston, MA, 2014, pp. 481–506.

Shapiro, Shawna, et al. “Teaching for Agency: From Appreciating Linguistic Diversity to Empowering Student Writers.” Composition Studies, vol. 44, no. 1, 2016, pp. 31–52.

Utah State University. "Learning Outcomes." Canvas, https://usu.instructure.com/courses/612705/pages/learning-outcomes. Note that if you aren't my boss or registered for this course, you can't actually access the page and will just have to take my word for it.

Freire, Paulo. “Chapter 2.” Pedagogy of the Oppressed, by Paulo Freire, Continuum., 1993, pp. 71–86.

Kitalong, Karla Saari, & Rebecca L. Miner. “Multimodal Composition Pedagogy Designed to Enhance Authors’ Personal Agency: Lessons from Non-Academic and Academic Composing Environments.” Computers and Composition, vol. 46, 2017, pp. 39–55., doi:10.1016/j.compcom.2017.09.007.

Miller, Carolyn R. “What Can Automation Tell Us About Agency?” Rhetoric Society Quarterly, vol. 37, no. 2, 2007, pp. 137–157., doi:10.1080/02773940601021197.

Ray, Brian, et al. “Rethinking SETs: Retuning Student Evaluations of Teaching for Student Agency.” Composition Studies, vol. 46, no. 1, 2018, pp. 34–56.

Selfe, Cynthia L. “Toward New Media Texts: Taking Up the Challenges of Visual Literacy.” The St. Martin's Guide to Teaching Writing, by Cheryl Glenn and Melissa A. Goldthwaite, Bedford/St. Martin's, Boston, MA, 2014, pp. 481–506.

Shapiro, Shawna, et al. “Teaching for Agency: From Appreciating Linguistic Diversity to Empowering Student Writers.” Composition Studies, vol. 44, no. 1, 2016, pp. 31–52.

Utah State University. "Learning Outcomes." Canvas, https://usu.instructure.com/courses/612705/pages/learning-outcomes. Note that if you aren't my boss or registered for this course, you can't actually access the page and will just have to take my word for it.