Review of Rod Dreher's "Live Not By Lies"

By C. Randall Nicholson

As a graduate instructor in the English department of Utah State University at the time of this writing (2021), I am a de facto member of the progressive establishment that Rod Dreher lambasts in his book Live Not By Lies: A Manual for Christian Dissidents. I suspect I'm actually the most conservative one there, but by Utah standards I may as well be a full-blown socialist. I classify my views as eclectic. So it comes as no surprise that I don't see eye-to-eye with Dreher on some things, but I welcomed reading his book to get outside my echo chamber and provide a course correction or counterbalance to some disturbing trends. I try to be open to adjusting my views. I've already done so many times; I used to be so right-wing that I thought Barack Obama was the literal Antichrist.

The main theme of the book is Dreher's alarm that we're living in a post-Christian era when Americans are facing, and will soon face more, professional and social consequences for expressing Christian or conservative views. (He mostly treats them as interchangeable.) He fears the development of a "soft totalitarianism" analogous, though not identical, to the Soviet Union's large-scale suppression, torture, and murder of Christians. Here I largely agree with him. I, too, am wary of cancel culture and the internet-driven mob mentality that manufactures a new outrage every other day and sometimes turns out to have been spectacularly wrong when all the facts are in. I don't share some of my colleagues' eagerness to remove a TED Talk by feminist and LGBTQ rights supporter Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie from their lesson plans after she supported a controversial essay on sex and gender by J.K. Rowling, or the university library's insistence on removing a quote by Rowling herself from one of its online modules used in my course because of her "statements against transgender rights". (How many of the librarians cared about transgender rights before 2016?) I don't even think Christian business owners should be crucified for refusing to cater same-sex weddings. A few days before reading this, I watched Rowan Atkinson's defense of the right to insulting speech in the United Kingdom and agreed with it entirely. It would be fair to say, then, that I agree with most of the book.

Though I don't think he goes nearly far enough, I appreciate Dreher's willingness to call out his own side in ways that few conservatives would. He criticizes "the US federal government's failure to respond effectively to the Covid-19 pandemic" (p. 29) which "caused mass suffering and revealed systemic decay in the habits and institutions of governing authority." (p. 30) He says that "Trump's exaltation of personal loyalty over expertise is discreditable and corrupting." Really, in a book about lies, Trump should have gotten his own chapter, and his cult of personality that constantly pretends he's a normal and decent human being and has to run damage control on everything he says should have gotten another one. Talk about making people believe that 2+2=5. I hope that if Dreher ever revises this book, he'll add something about the 2020 presidential election. Surely Christians should live not by lies about vote fraud. He condemned the Capitol riot on his blog, but then, he also explained it away as "an equal and positive reaction" to soft totalitarianism blaming white people for everything.

What really shocks and impresses me is the presence of an entire chapter on the role of capitalism in the approaching soft totalitarianism. (Chapter 4, "Capitalism, Woke and Watchful") Whenever I criticize capitalism in any way, conservatives hasten to remind me that capitalism is flawless and the solution to all the world's problems, and retort with "But socialism" this and "But socialism" that even though I never mentioned socialism. Dreher correctly notes that "[a]s institutions of private enterprise, corporations were seen by conservatives as more naturally virtuous than the state" (p. 72) and correctly explains that this is nonsense. I appreciate his integrity in that regard.

I don't think living in a post-Christian era is all bad. It poses major challenges that I'd just as soon do without, for sure, but it enables more meaningful choices and more committed discipleship. Nobody should be a Christian just because Christianity is the cultural norm. (And Christians did some terrible things to make it the cultural norm in the first place.) I also happen to share the perspective of Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel: "It is customary to blame secular science and anti-religious philosophy for the eclipse of religion in modern society. It would be more honest to blame religion for its own defeats. Religion declined not because it was refuted, but because it became irrelevant, dull, oppressive, insipid. When faith is completely replaced by creed, worship by discipline, love by habit; when the crisis of today is ignored because of the splendor of the past; when faith becomes an heirloom rather than a living fountain; when religion speaks only in the name of authority rather than with the voice of compassion - its message becomes meaningless." Notably, this quote from 1955 predates the sexual revolution and what we usually think of as the secularization of American society. Dreher also has some harsh words for modern Christianity, but places far more of the blame for its decline elsewhere than I think is warranted. If Christianity filled people's needs then they wouldn't go looking for a replacement.

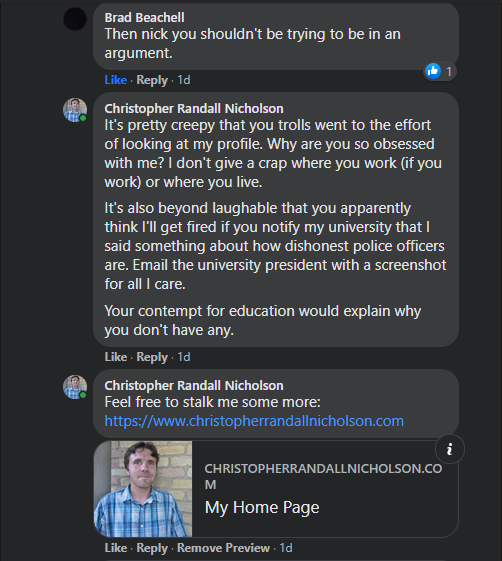

I think Dreher's narrative of cancel culture's chilling effect on non-celebrities' and non-academics' free expression is quite exaggerated. That's not to say it won't get worse, but here in Utah, conservatism is the mainstream, and nobody is shy about expressing it. Liberals (and I include myself in this case, though I don't self-identify as a liberal) are the ones often made to feel uncomfortable and unwelcome in church by people who think Republican talking points are scripture. Many readers of the Deseret News are so out of touch with reality that they think it's promoting a leftist agenda and contradicting the gospel whenever it reports news or prints an editorial that varies from those talking points in any respect. They mock and distrust the media in this case not for lying, but for being honest about things they don't want to hear. Its online comments sections are rampant with almost the worst that the right wing has to offer - racism, xenophobia, anti-intellectualism, anti-feminism, bootlicking, victim-blaming, conspiracy theories, science denial, medical misinformation, and so on - things that people should be embarrassed to say or write but obviously aren't. Even in the comments of the Salt Lake Tribune, an actual liberal publication whose usual commenters are very hostile to Christianity and conservatism, right-wingers who hold education in contempt have harassed me because of my profession.

The main theme of the book is Dreher's alarm that we're living in a post-Christian era when Americans are facing, and will soon face more, professional and social consequences for expressing Christian or conservative views. (He mostly treats them as interchangeable.) He fears the development of a "soft totalitarianism" analogous, though not identical, to the Soviet Union's large-scale suppression, torture, and murder of Christians. Here I largely agree with him. I, too, am wary of cancel culture and the internet-driven mob mentality that manufactures a new outrage every other day and sometimes turns out to have been spectacularly wrong when all the facts are in. I don't share some of my colleagues' eagerness to remove a TED Talk by feminist and LGBTQ rights supporter Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie from their lesson plans after she supported a controversial essay on sex and gender by J.K. Rowling, or the university library's insistence on removing a quote by Rowling herself from one of its online modules used in my course because of her "statements against transgender rights". (How many of the librarians cared about transgender rights before 2016?) I don't even think Christian business owners should be crucified for refusing to cater same-sex weddings. A few days before reading this, I watched Rowan Atkinson's defense of the right to insulting speech in the United Kingdom and agreed with it entirely. It would be fair to say, then, that I agree with most of the book.

Though I don't think he goes nearly far enough, I appreciate Dreher's willingness to call out his own side in ways that few conservatives would. He criticizes "the US federal government's failure to respond effectively to the Covid-19 pandemic" (p. 29) which "caused mass suffering and revealed systemic decay in the habits and institutions of governing authority." (p. 30) He says that "Trump's exaltation of personal loyalty over expertise is discreditable and corrupting." Really, in a book about lies, Trump should have gotten his own chapter, and his cult of personality that constantly pretends he's a normal and decent human being and has to run damage control on everything he says should have gotten another one. Talk about making people believe that 2+2=5. I hope that if Dreher ever revises this book, he'll add something about the 2020 presidential election. Surely Christians should live not by lies about vote fraud. He condemned the Capitol riot on his blog, but then, he also explained it away as "an equal and positive reaction" to soft totalitarianism blaming white people for everything.

What really shocks and impresses me is the presence of an entire chapter on the role of capitalism in the approaching soft totalitarianism. (Chapter 4, "Capitalism, Woke and Watchful") Whenever I criticize capitalism in any way, conservatives hasten to remind me that capitalism is flawless and the solution to all the world's problems, and retort with "But socialism" this and "But socialism" that even though I never mentioned socialism. Dreher correctly notes that "[a]s institutions of private enterprise, corporations were seen by conservatives as more naturally virtuous than the state" (p. 72) and correctly explains that this is nonsense. I appreciate his integrity in that regard.

I don't think living in a post-Christian era is all bad. It poses major challenges that I'd just as soon do without, for sure, but it enables more meaningful choices and more committed discipleship. Nobody should be a Christian just because Christianity is the cultural norm. (And Christians did some terrible things to make it the cultural norm in the first place.) I also happen to share the perspective of Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel: "It is customary to blame secular science and anti-religious philosophy for the eclipse of religion in modern society. It would be more honest to blame religion for its own defeats. Religion declined not because it was refuted, but because it became irrelevant, dull, oppressive, insipid. When faith is completely replaced by creed, worship by discipline, love by habit; when the crisis of today is ignored because of the splendor of the past; when faith becomes an heirloom rather than a living fountain; when religion speaks only in the name of authority rather than with the voice of compassion - its message becomes meaningless." Notably, this quote from 1955 predates the sexual revolution and what we usually think of as the secularization of American society. Dreher also has some harsh words for modern Christianity, but places far more of the blame for its decline elsewhere than I think is warranted. If Christianity filled people's needs then they wouldn't go looking for a replacement.

I think Dreher's narrative of cancel culture's chilling effect on non-celebrities' and non-academics' free expression is quite exaggerated. That's not to say it won't get worse, but here in Utah, conservatism is the mainstream, and nobody is shy about expressing it. Liberals (and I include myself in this case, though I don't self-identify as a liberal) are the ones often made to feel uncomfortable and unwelcome in church by people who think Republican talking points are scripture. Many readers of the Deseret News are so out of touch with reality that they think it's promoting a leftist agenda and contradicting the gospel whenever it reports news or prints an editorial that varies from those talking points in any respect. They mock and distrust the media in this case not for lying, but for being honest about things they don't want to hear. Its online comments sections are rampant with almost the worst that the right wing has to offer - racism, xenophobia, anti-intellectualism, anti-feminism, bootlicking, victim-blaming, conspiracy theories, science denial, medical misinformation, and so on - things that people should be embarrassed to say or write but obviously aren't. Even in the comments of the Salt Lake Tribune, an actual liberal publication whose usual commenters are very hostile to Christianity and conservatism, right-wingers who hold education in contempt have harassed me because of my profession.

Furthermore, while the excesses are alarming, some people should face professional and social consequences for the views they express. At the time of this writing, self-appointed alt-right defenders of my church who have been using fake Twitter profiles to anonymously post racist, sexist, anti-Semitic, and violent content under #DezNat (Deseret Nation) are scattering like cockroaches as their true identities are exposed. One of their founding members turned out to be Matthias Cicotte, an assistant attorney general in the Alaska Department of Law. Among other things, he advocated for the execution of people who undergo gender reassignment surgery. His government position put him in charge of civil rights cases. Another, Kevin Dolan, was a senior data scientist at a firm that works with military and intelligence agencies. I could not possibly be happier about both of these men losing their jobs. Yet I got into an argument with a conservative who felt that Cicotte had been victimized because doxxing is "dangerous and wrong", and told me that Nazis should be able to march in a town populated by Holocaust survivors without facing professional or social consequences (I said nothing about legal consequences). I told him in rather un-Christian terminology exactly what I thought of him.

So where should we draw the line? I don't know, but I'm sure I would draw it much closer than Dreher, who somehow finds cause for concern in the fact that "the global online payments transfer system PayPal refuses to let white supremacist groups use its services." (p. 89) He doesn't support white supremacist groups, but he sees this refusal as a slippery slope instead of common sense.

The blanket contempt for "political correctness" throughout the book is overblown as well. Again, it has its excesses that should be, pun intended, corrected, especially when they make people afraid to tell the truth, but at its root the basic concept is just to not be a jerk to people who are different from you. I don't think Dreher would fit in this category, but many if not most of the people I see complaining about "political correctness" are clearly just bitter that they can no longer call someone a retard without catching flack, and that's all I can think of when he uses the term dismissively over and over again. It's easy to accuse people of being "too sensitive" to slurs and hate speech when you've never been on the receiving end. Dreher makes political correctness just as much of a "thoughtcrime" as he accuses those on the left of making other things.

Drawing on the writings of sociologist Philip Rieff, Dreher comes back repeatedly to the idea that "Religious Man, who lived according to belief in transcendent principles that ordered human life around communal purposes, had given way to Psychological Man, who believed that there was no transcendent order and that life's purpose was to find one's own way experimentally." (p. 11) But as Scott M. Kenworthy notes in his review, "Dreher mistakenly identifies the modern self exclusively with freedom of sexual expression and gender identity. In fact, the assumption of the modern self is at the core of the 'old-fashioned liberalism' that Dreher lauds, with its strong emphasis on individual rights that can be traced back to the Enlightenment. Socialism at least maintained some sense of the common good beyond the individual. The entire function of advanced capitalism depends on the modern notion of the self, and this has nothing to do with conservative or liberal. If anything, the Right has been the most deeply uncritical champion of consumer capitalism, which conservative Christians have also wholeheartedly embraced since the Cold War."

If progressives really believe that life revolves around their own happiness and nothing else, as Dreher repeatedly claims, then I'm hard-pressed to understand the social justice ideology he repeatedly criticizes. Why would people who believe their own happiness is the highest meaning in life devote themselves with such gusto to promoting equal rights and dignity for other people? And why is it that during this pandemic, they are the ones begging everyone to follow public health guidelines to protect their communities, while conservatives insist that they have no such obligation to anyone else or anything larger than themselves? Progressives are not the ones who throw temper tantrums about having to wear masks in public. Progressives are not the ones who keep saying "People die every day" and "99% survival rate" and "Most of them are over 65 or have pre-existing conditions" until I feel like disowning my country. This is one area where Dreher should have continued calling out his own side. He's one hundred percent correct about one thing, though: this self-centered attitude is fundamentally and irreconcilably incompatible with Christianity.

Dreher reveals that "A Soviet-born US physician told me... that social justice ideology is forcing physicians like him to ignore their medical training and judgment when it comes to transgender health. He said it is not permissible within his institution to advise gender-dysphoric patients against treatments they desire, even when a physician believes it is not in that particular patient's health interest." (p. 41) He expresses alarm about "policies, laws, and court decisions that diminish or sever parental rights in cases involving transgender minors." (p. 132) I share these concerns. But his initial description of "[t]he transgender phenomenon, which requires affirming psychology over biological reality" (p. 13), though surely true in some cases, is an oversimplification. The "biological reality" he alludes to - one where chromosomes, hormone levels, genitals, and secondary sex characteristics always match and line up along a dichotomy of unambiguously male or unambiguously female - is not biological reality at all. Conservative Christians' refusal to acknowledge the scientific complexity of sex and gender is probably the real reason they have no credibility on those subjects. (My church didn't acknowledge that intersex people exist until 2020.) I don't pretend to understand it even after reading a fair amount, but I don't pretend it doesn't exist either. Even from a purely religious perspective, I have yet to see a compelling argument for why a female spirit couldn't develop a male body or vice versa. "God doesn't make mistakes" just won't cut it when literally anything else that could go wrong with a body's development does.

Dreher laments, "According to Gallup, Americans' confidence in their institutions - political, media, religious, legal, medical, corporate - is at historic lows across the board. Only the military, the police, and small businesses retain the strong confidence of over 50 percent." (p. 33) He warns that such a loss of institutional trust sets the stage for totalitarianism. What he glosses over entirely is why this happened. Nearly all of the institutions listed, including two of the three that inexplicably retain over 50 percent confidence, have been racked with so many scandals that people barely take notice of the latest ones. Dreher brings up Edward Snowden and the NSA's illegal spying later in the book, so I don't know why he implies here that the loss of trust in government is driven by nothing more than the progressive agenda. And we all know churches aren't guiltless by a long shot either. I never fully regained trust in my own church after discovering that the dumbed-down and sanitized version of its history it had fed me through manuals, magazines, and conferences was less than accurate. Global leaders have taught incorrect, even harmful things (especially about black people and women), and local leaders have sometimes let me down when I needed them the most. I try to place my trust only in God. My church is not God, it's only a means of drawing closer to Him and multiplying my influence for good by unifying me with other believers, though unfortunately that includes the ones who infest Deseret News comments sections.

"At universities within the University of California system, for example," Dreher writes, "teachers who want to apply for tenure-track positions have to affirm their commitment to 'equity, diversity, and inclusion' - and to have demonstrated it, even if it has nothing to do with their field. Similar politically correct loyalty oaths are required at leading public and private schools." (p. 40) He refers to an anonymous professor who complained to him that "his humanities department decided to require from job applicants a formal statement of loyalty to the ideology of diversity - even though this has nothing to do with teaching ability or scholarship." (p. 58) As a teacher, I say with confidence that "equity, diversity, and inclusion" are entirely relevant to any field I could conceivably teach, for the simple reason that my students are people. Any teacher who isn't concerned about students as people shouldn't be a teacher. When I have a student who speaks English as a second language, when I have two students who look different than anyone else in the class and 86.6% of my city's population, and when I know from a recent study that female students in small groups are routinely ignored and interrupted, these are not abstract or irrelevant concerns. I also decide which voices to amplify when I decide which readings and videos to give my students. When the only people students see achieving things in their field are white males, that shapes their understanding of the world in a bad way.

Dreher says, "The modern age is built on the Myth of Progress.... Believers in the Myth of Progress hold that the present is better than the past, and that the future will inevitably be better than the present." (p. 48, emphasis in original) Huh? I get the Myth of Progress, and that it's fundamental to people on both sides of the political spectrum, but I've never heard of anyone claiming that progress is inevitable. SJWs certainly don't believe that, or they wouldn't need to fight so hard for it and they wouldn't have been so terrified when Trump got elected. (I mean in 2016, the one time that he actually won an election.) Progressives on the whole don't strike me as being very optimistic about the future at all. They're concerned that race relations are deteriorating, gender equality isn't getting better anytime soon, the inequality in wealth distribution is skyrocketing, and human-prompted environmental disasters are ruining life as we know it. I'm certainly not optimistic about the future. I think my own life will turn out all right, but I fully expect that the United States and most of the world will continue to be an unholy dumpster fire until Jesus comes and burns it with holy fire. And while I used to believe, as most conservatives do, that this country had undergone a consistent progression from "more racist" to "less racist", that racism had all but died out after we passed some laws against it in the 1960s, I now understand from studying history that it's ebbed and flowed quite a bit and may do so again. There's nothing inevitable about it.

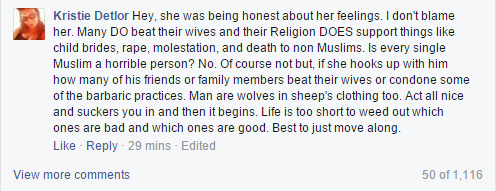

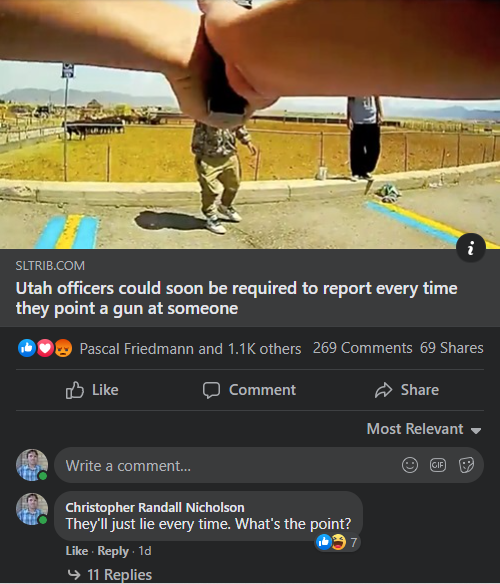

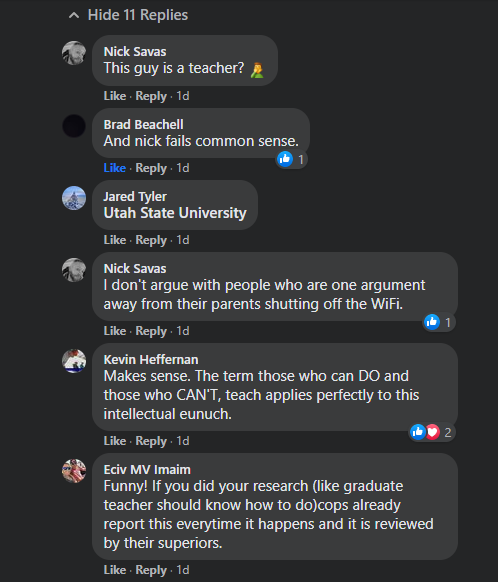

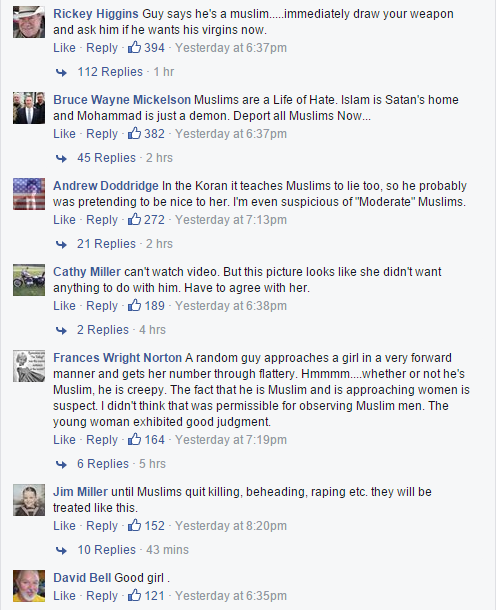

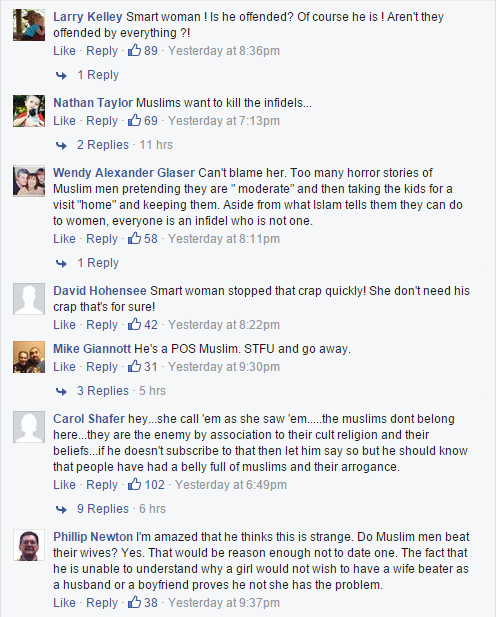

Dreher quotes Sir Roger Scruton telling him in an interview, "It's just like 'homophobia' or 'Islamophobia,' these new thoughtcrimes. What on earth do they mean?" (p. 57) Scruton is being highly disingenuous if he's really pretending not to be aware of the rampant right-wing bigotry against rank-and-file Muslims. On my more cynical days, I feel like it's the key defining trait of conservatism. Members of my church who hate it when outsiders cherry-pick and distort their beliefs often have no qualms about cherry-picking and distorting Muslim beliefs. At one point or another I've unfollowed dozens of conservative Facebook pages and personalities for spewing prejudice against Muslims (or "Muslimes" or "Muzzies" as they sometimes say). Here are some screenshots I took a few years ago, probably right before I left the page.

So where should we draw the line? I don't know, but I'm sure I would draw it much closer than Dreher, who somehow finds cause for concern in the fact that "the global online payments transfer system PayPal refuses to let white supremacist groups use its services." (p. 89) He doesn't support white supremacist groups, but he sees this refusal as a slippery slope instead of common sense.

The blanket contempt for "political correctness" throughout the book is overblown as well. Again, it has its excesses that should be, pun intended, corrected, especially when they make people afraid to tell the truth, but at its root the basic concept is just to not be a jerk to people who are different from you. I don't think Dreher would fit in this category, but many if not most of the people I see complaining about "political correctness" are clearly just bitter that they can no longer call someone a retard without catching flack, and that's all I can think of when he uses the term dismissively over and over again. It's easy to accuse people of being "too sensitive" to slurs and hate speech when you've never been on the receiving end. Dreher makes political correctness just as much of a "thoughtcrime" as he accuses those on the left of making other things.

Drawing on the writings of sociologist Philip Rieff, Dreher comes back repeatedly to the idea that "Religious Man, who lived according to belief in transcendent principles that ordered human life around communal purposes, had given way to Psychological Man, who believed that there was no transcendent order and that life's purpose was to find one's own way experimentally." (p. 11) But as Scott M. Kenworthy notes in his review, "Dreher mistakenly identifies the modern self exclusively with freedom of sexual expression and gender identity. In fact, the assumption of the modern self is at the core of the 'old-fashioned liberalism' that Dreher lauds, with its strong emphasis on individual rights that can be traced back to the Enlightenment. Socialism at least maintained some sense of the common good beyond the individual. The entire function of advanced capitalism depends on the modern notion of the self, and this has nothing to do with conservative or liberal. If anything, the Right has been the most deeply uncritical champion of consumer capitalism, which conservative Christians have also wholeheartedly embraced since the Cold War."

If progressives really believe that life revolves around their own happiness and nothing else, as Dreher repeatedly claims, then I'm hard-pressed to understand the social justice ideology he repeatedly criticizes. Why would people who believe their own happiness is the highest meaning in life devote themselves with such gusto to promoting equal rights and dignity for other people? And why is it that during this pandemic, they are the ones begging everyone to follow public health guidelines to protect their communities, while conservatives insist that they have no such obligation to anyone else or anything larger than themselves? Progressives are not the ones who throw temper tantrums about having to wear masks in public. Progressives are not the ones who keep saying "People die every day" and "99% survival rate" and "Most of them are over 65 or have pre-existing conditions" until I feel like disowning my country. This is one area where Dreher should have continued calling out his own side. He's one hundred percent correct about one thing, though: this self-centered attitude is fundamentally and irreconcilably incompatible with Christianity.

Dreher reveals that "A Soviet-born US physician told me... that social justice ideology is forcing physicians like him to ignore their medical training and judgment when it comes to transgender health. He said it is not permissible within his institution to advise gender-dysphoric patients against treatments they desire, even when a physician believes it is not in that particular patient's health interest." (p. 41) He expresses alarm about "policies, laws, and court decisions that diminish or sever parental rights in cases involving transgender minors." (p. 132) I share these concerns. But his initial description of "[t]he transgender phenomenon, which requires affirming psychology over biological reality" (p. 13), though surely true in some cases, is an oversimplification. The "biological reality" he alludes to - one where chromosomes, hormone levels, genitals, and secondary sex characteristics always match and line up along a dichotomy of unambiguously male or unambiguously female - is not biological reality at all. Conservative Christians' refusal to acknowledge the scientific complexity of sex and gender is probably the real reason they have no credibility on those subjects. (My church didn't acknowledge that intersex people exist until 2020.) I don't pretend to understand it even after reading a fair amount, but I don't pretend it doesn't exist either. Even from a purely religious perspective, I have yet to see a compelling argument for why a female spirit couldn't develop a male body or vice versa. "God doesn't make mistakes" just won't cut it when literally anything else that could go wrong with a body's development does.

Dreher laments, "According to Gallup, Americans' confidence in their institutions - political, media, religious, legal, medical, corporate - is at historic lows across the board. Only the military, the police, and small businesses retain the strong confidence of over 50 percent." (p. 33) He warns that such a loss of institutional trust sets the stage for totalitarianism. What he glosses over entirely is why this happened. Nearly all of the institutions listed, including two of the three that inexplicably retain over 50 percent confidence, have been racked with so many scandals that people barely take notice of the latest ones. Dreher brings up Edward Snowden and the NSA's illegal spying later in the book, so I don't know why he implies here that the loss of trust in government is driven by nothing more than the progressive agenda. And we all know churches aren't guiltless by a long shot either. I never fully regained trust in my own church after discovering that the dumbed-down and sanitized version of its history it had fed me through manuals, magazines, and conferences was less than accurate. Global leaders have taught incorrect, even harmful things (especially about black people and women), and local leaders have sometimes let me down when I needed them the most. I try to place my trust only in God. My church is not God, it's only a means of drawing closer to Him and multiplying my influence for good by unifying me with other believers, though unfortunately that includes the ones who infest Deseret News comments sections.

"At universities within the University of California system, for example," Dreher writes, "teachers who want to apply for tenure-track positions have to affirm their commitment to 'equity, diversity, and inclusion' - and to have demonstrated it, even if it has nothing to do with their field. Similar politically correct loyalty oaths are required at leading public and private schools." (p. 40) He refers to an anonymous professor who complained to him that "his humanities department decided to require from job applicants a formal statement of loyalty to the ideology of diversity - even though this has nothing to do with teaching ability or scholarship." (p. 58) As a teacher, I say with confidence that "equity, diversity, and inclusion" are entirely relevant to any field I could conceivably teach, for the simple reason that my students are people. Any teacher who isn't concerned about students as people shouldn't be a teacher. When I have a student who speaks English as a second language, when I have two students who look different than anyone else in the class and 86.6% of my city's population, and when I know from a recent study that female students in small groups are routinely ignored and interrupted, these are not abstract or irrelevant concerns. I also decide which voices to amplify when I decide which readings and videos to give my students. When the only people students see achieving things in their field are white males, that shapes their understanding of the world in a bad way.

Dreher says, "The modern age is built on the Myth of Progress.... Believers in the Myth of Progress hold that the present is better than the past, and that the future will inevitably be better than the present." (p. 48, emphasis in original) Huh? I get the Myth of Progress, and that it's fundamental to people on both sides of the political spectrum, but I've never heard of anyone claiming that progress is inevitable. SJWs certainly don't believe that, or they wouldn't need to fight so hard for it and they wouldn't have been so terrified when Trump got elected. (I mean in 2016, the one time that he actually won an election.) Progressives on the whole don't strike me as being very optimistic about the future at all. They're concerned that race relations are deteriorating, gender equality isn't getting better anytime soon, the inequality in wealth distribution is skyrocketing, and human-prompted environmental disasters are ruining life as we know it. I'm certainly not optimistic about the future. I think my own life will turn out all right, but I fully expect that the United States and most of the world will continue to be an unholy dumpster fire until Jesus comes and burns it with holy fire. And while I used to believe, as most conservatives do, that this country had undergone a consistent progression from "more racist" to "less racist", that racism had all but died out after we passed some laws against it in the 1960s, I now understand from studying history that it's ebbed and flowed quite a bit and may do so again. There's nothing inevitable about it.

Dreher quotes Sir Roger Scruton telling him in an interview, "It's just like 'homophobia' or 'Islamophobia,' these new thoughtcrimes. What on earth do they mean?" (p. 57) Scruton is being highly disingenuous if he's really pretending not to be aware of the rampant right-wing bigotry against rank-and-file Muslims. On my more cynical days, I feel like it's the key defining trait of conservatism. Members of my church who hate it when outsiders cherry-pick and distort their beliefs often have no qualms about cherry-picking and distorting Muslim beliefs. At one point or another I've unfollowed dozens of conservative Facebook pages and personalities for spewing prejudice against Muslims (or "Muslimes" or "Muzzies" as they sometimes say). Here are some screenshots I took a few years ago, probably right before I left the page.

Does that make it clear enough what Islamophobia means? For the record, yes, I think most of the commenters on this post should have faced professional and social consequences for expressing their conservative views. Instead, they nominated and then elected a president with a history of anti-Muslim comments, including a call "for a total and complete shutdown of Muslims entering the United States", which, according to conservatives, had absolutely nothing to do with his unwarranted travel and refugee ban against several Muslim-majority countries a little over a year later.

Dreher writes, "In the cult of social justice, the oppressors are generally white, male, heterosexual, and Christian. The oppressed are racial minorities, women, sexual minorities, and religious minorities." (p. 61) He implies that these groupings are arbitrary when in fact they're a pretty good summary of this country's entire history. His derisive comparison of "a white Pentecostal man living on disability in a trailer park" to "a black lesbian Ivy League professor" is a straw man. First of all, people with disabilities are also considered an oppressed group (which he should know, because he includes ableism on a list of "thoughtcrimes" just three pages earlier). Second, the existence of his hypothetical black lesbian professor would not alter the statistical realities that black people and women are both vastly underrepresented in academia. Third, nobody anywhere is claiming that all white male heterosexual Christians have great lives. The actual argument is that when a white male heterosexual Christian in the United States does encounter difficulties and disappointments, he can rest fairly assured that they aren't because of his race, sex, sexual orientation, or religion. His life is not adversely impacted by the results of centuries of discrimination against his race, sex, sexual orientation, or religion, and he doesn't go through every day with a constant awareness of those attributes weighing on his mind. He doesn't live in fear of being raped or murdered when he goes out jogging. I find identity politics annoying and don't always agree with how they're used, but pretending various identity markers don't matter won't make it so.

Dreher also notes that "If one is not a member of an oppressed group, he or she can become an 'ally' in the power struggle." (p. 62) Why does he imply this to be a bad thing? According to my understanding, being an ally to oppressed groups is at the very core of Christianity whether you describe it with the scary SJW buzzwords or not. I, a white male Christian myself, am part of at least two "oppressed groups", being autistic and a sexual minority that most people don't know exists - and I've suffered for it from my earliest childhood to this day - but I still feel a calling in life to speak up for others whose voices don't get the attention they deserve. When I was a conservative, if a black person claimed to experience racism that I couldn't identify with because I'm not black, or a woman claimed to experience sexism that I couldn't identify with because I'm not a woman - in other words, if someone claimed to have a different life experience than mine that put my beloved country in a less than flawless light, I assumed they were either making it up or misjudging the situation. Now I strive to listen to and develop empathy for people whose life experiences differ from mine. A true Christian can do no less.

In his review, which raises important points even though on the whole I find it excessively negative, Benjamin J. Dueholm opines, "Religious and ideological identity is only one axis for the conservative understanding of modern politics. The other axis is ethnic and cultural. Talking about Christians in Soviet Eastern Europe offers Dreher and his audience both a villain that is ideologically other (namely, communist) and a protagonist who is ethno-culturally self (European and Christian). The story of Christianity under racial apartheid in America, democratic retraction in contemporary Europe, or criminal and failed states in Latin America would require Dreher and his readers to face the possibility of identifying with the persecutor or being estranged from the persecuted." I doubt this was a conscious decision, but maybe it's a significant one. Again, empathy.

Dreher cites "the 2015 Yale University clash between professors Nicholas and Erika Christakis and enraged students from the residential college overseen by the faculty couple. Things went very badly for the Christakises, old-school liberals who erred by thinking that the students could be engaged with the tools and procedures of reason. Alas, the students were in the grip of the religion of social justice." (p. 62-3) I wasn't familiar with this incident, so I looked it up. It was an unfortunate incident that led to the Christakises both choosing to resign their positions months later. The campus climate that fostered it is a cause for concern. But as it turns out, Dreher neglects to mention that ninety-one Yale faculty members signed a letter supporting them, and The Atlantic and liberal atheist pundit Bill Maher condemned the students' behavior. In 2018, Nicholas Christakis was appointed to Yale's highest faculty rank, Sterling Professor. These details kind of undermine Dreher's use of the incident to demonstrate a monolithic progressive establishment quashing conservative views.

Perhaps the greatest weakness of this book is that its author rarely if ever lets liberals, progressives, or SJWs explain their ideology and goals in their own words. He quotes from former Soviet citizens alarmed by similarities between that regime and current conditions in the US, and he quotes from conservative authors telling us what liberals believe, but that's about it. He depicts everyone on the left as a unified coalition with identical ideology and goals. As Dueholm points out in his review, "Dreher never directly cites the people he claims are driving our world toward totalitarianism. He doesn’t acknowledge the differences between the managerial antiracism of Robin DiAngelo and the Afro-pessimism of someone like Frank Wilderson III, let alone the fractious debates within the broad left over whether and how to integrate ethnic, gender, or sexual identity politics with egalitarian economic goals. His definition of social justice comes from an atheist math professor, with rambunctious college students and tech industry titans massed into a single engine that rolls over everyone in its progressive path." As of this writing, I, for one, do not have any ties to Hollywood or Silicon Valley, or even to academics at other universities.

It's inevitable that conservatives and liberals will disagree on ideology and approach. When liberals put forth solutions to social problems like systemic racism and police brutality that conservatives don't like, conservatives should put forth alternative solutions more in line with their own philosophy - but instead, for the most part they've opted to deny that those problems exist, or at best claim that they'll magically disappear if we stop talking about them. (The same is true of scientific problems like climate change and global pandemics, but I suppose that would be a tangent.) In a recent piece aptly titled "Structural Racism Isn't Wokeness, It's Reality", conservative writer David French makes this point by quoting Dreher's own statement that "the business of a conservatism with integrity is not to impose an idealistic ideological narrative on reality but rather to try to see the world as it is and respond to its challenges within the limits of what we know about human nature." Live Not By Lies would have been more powerful in my view if it suggested ways for conservative Christians to proactively address social problems instead of merely resisting and dissenting from those who do. I believe this failure on their part is, again, a major factor in Christianity's decline in the United States. Dreher rightly points to its foundational role in the civil rights movement (which, it should be noted, many conservatives dismissed as a Communist conspiracy), but what has it done lately?

I think this book's greatest strength, hands down, is the final chapter, "The Gift of Suffering". Even if the rest of Live Not By Lies were without merit - which, despite my nitpicking, it isn't by a long shot - the message of this chapter would be profound and applicable. Here, Dreher pushes back against "Christianity without tears" and the belief that the purpose of life is to have a good time. Nobody welcomes suffering, but it is a fact of life and something we need to be prepared to go through in a productive manner. Jesus was very clear on this point. "Blessed are ye, when men shall revile you, and persecute you, and shall say all manner of evil against you falsely, for my sake. Rejoice, and be exceeding glad: for great is your reward in heaven: for so persecuted they the prophets which were before you." (Matthew 5:11-12) I felt very edified after reading this chapter. My attitude toward suffering is usually one of resentment and impatience. I know I need to reorient my thinking to see myself suffering with Christ and for Christ and to see a higher purpose and long-term benefit than just trying to avoid it until I die. I would be interested to read a work by Dreher that just discusses his views on Christianity and leaves out politics altogether.

Dreher writes, "In the cult of social justice, the oppressors are generally white, male, heterosexual, and Christian. The oppressed are racial minorities, women, sexual minorities, and religious minorities." (p. 61) He implies that these groupings are arbitrary when in fact they're a pretty good summary of this country's entire history. His derisive comparison of "a white Pentecostal man living on disability in a trailer park" to "a black lesbian Ivy League professor" is a straw man. First of all, people with disabilities are also considered an oppressed group (which he should know, because he includes ableism on a list of "thoughtcrimes" just three pages earlier). Second, the existence of his hypothetical black lesbian professor would not alter the statistical realities that black people and women are both vastly underrepresented in academia. Third, nobody anywhere is claiming that all white male heterosexual Christians have great lives. The actual argument is that when a white male heterosexual Christian in the United States does encounter difficulties and disappointments, he can rest fairly assured that they aren't because of his race, sex, sexual orientation, or religion. His life is not adversely impacted by the results of centuries of discrimination against his race, sex, sexual orientation, or religion, and he doesn't go through every day with a constant awareness of those attributes weighing on his mind. He doesn't live in fear of being raped or murdered when he goes out jogging. I find identity politics annoying and don't always agree with how they're used, but pretending various identity markers don't matter won't make it so.

Dreher also notes that "If one is not a member of an oppressed group, he or she can become an 'ally' in the power struggle." (p. 62) Why does he imply this to be a bad thing? According to my understanding, being an ally to oppressed groups is at the very core of Christianity whether you describe it with the scary SJW buzzwords or not. I, a white male Christian myself, am part of at least two "oppressed groups", being autistic and a sexual minority that most people don't know exists - and I've suffered for it from my earliest childhood to this day - but I still feel a calling in life to speak up for others whose voices don't get the attention they deserve. When I was a conservative, if a black person claimed to experience racism that I couldn't identify with because I'm not black, or a woman claimed to experience sexism that I couldn't identify with because I'm not a woman - in other words, if someone claimed to have a different life experience than mine that put my beloved country in a less than flawless light, I assumed they were either making it up or misjudging the situation. Now I strive to listen to and develop empathy for people whose life experiences differ from mine. A true Christian can do no less.

In his review, which raises important points even though on the whole I find it excessively negative, Benjamin J. Dueholm opines, "Religious and ideological identity is only one axis for the conservative understanding of modern politics. The other axis is ethnic and cultural. Talking about Christians in Soviet Eastern Europe offers Dreher and his audience both a villain that is ideologically other (namely, communist) and a protagonist who is ethno-culturally self (European and Christian). The story of Christianity under racial apartheid in America, democratic retraction in contemporary Europe, or criminal and failed states in Latin America would require Dreher and his readers to face the possibility of identifying with the persecutor or being estranged from the persecuted." I doubt this was a conscious decision, but maybe it's a significant one. Again, empathy.

Dreher cites "the 2015 Yale University clash between professors Nicholas and Erika Christakis and enraged students from the residential college overseen by the faculty couple. Things went very badly for the Christakises, old-school liberals who erred by thinking that the students could be engaged with the tools and procedures of reason. Alas, the students were in the grip of the religion of social justice." (p. 62-3) I wasn't familiar with this incident, so I looked it up. It was an unfortunate incident that led to the Christakises both choosing to resign their positions months later. The campus climate that fostered it is a cause for concern. But as it turns out, Dreher neglects to mention that ninety-one Yale faculty members signed a letter supporting them, and The Atlantic and liberal atheist pundit Bill Maher condemned the students' behavior. In 2018, Nicholas Christakis was appointed to Yale's highest faculty rank, Sterling Professor. These details kind of undermine Dreher's use of the incident to demonstrate a monolithic progressive establishment quashing conservative views.

Perhaps the greatest weakness of this book is that its author rarely if ever lets liberals, progressives, or SJWs explain their ideology and goals in their own words. He quotes from former Soviet citizens alarmed by similarities between that regime and current conditions in the US, and he quotes from conservative authors telling us what liberals believe, but that's about it. He depicts everyone on the left as a unified coalition with identical ideology and goals. As Dueholm points out in his review, "Dreher never directly cites the people he claims are driving our world toward totalitarianism. He doesn’t acknowledge the differences between the managerial antiracism of Robin DiAngelo and the Afro-pessimism of someone like Frank Wilderson III, let alone the fractious debates within the broad left over whether and how to integrate ethnic, gender, or sexual identity politics with egalitarian economic goals. His definition of social justice comes from an atheist math professor, with rambunctious college students and tech industry titans massed into a single engine that rolls over everyone in its progressive path." As of this writing, I, for one, do not have any ties to Hollywood or Silicon Valley, or even to academics at other universities.

It's inevitable that conservatives and liberals will disagree on ideology and approach. When liberals put forth solutions to social problems like systemic racism and police brutality that conservatives don't like, conservatives should put forth alternative solutions more in line with their own philosophy - but instead, for the most part they've opted to deny that those problems exist, or at best claim that they'll magically disappear if we stop talking about them. (The same is true of scientific problems like climate change and global pandemics, but I suppose that would be a tangent.) In a recent piece aptly titled "Structural Racism Isn't Wokeness, It's Reality", conservative writer David French makes this point by quoting Dreher's own statement that "the business of a conservatism with integrity is not to impose an idealistic ideological narrative on reality but rather to try to see the world as it is and respond to its challenges within the limits of what we know about human nature." Live Not By Lies would have been more powerful in my view if it suggested ways for conservative Christians to proactively address social problems instead of merely resisting and dissenting from those who do. I believe this failure on their part is, again, a major factor in Christianity's decline in the United States. Dreher rightly points to its foundational role in the civil rights movement (which, it should be noted, many conservatives dismissed as a Communist conspiracy), but what has it done lately?

I think this book's greatest strength, hands down, is the final chapter, "The Gift of Suffering". Even if the rest of Live Not By Lies were without merit - which, despite my nitpicking, it isn't by a long shot - the message of this chapter would be profound and applicable. Here, Dreher pushes back against "Christianity without tears" and the belief that the purpose of life is to have a good time. Nobody welcomes suffering, but it is a fact of life and something we need to be prepared to go through in a productive manner. Jesus was very clear on this point. "Blessed are ye, when men shall revile you, and persecute you, and shall say all manner of evil against you falsely, for my sake. Rejoice, and be exceeding glad: for great is your reward in heaven: for so persecuted they the prophets which were before you." (Matthew 5:11-12) I felt very edified after reading this chapter. My attitude toward suffering is usually one of resentment and impatience. I know I need to reorient my thinking to see myself suffering with Christ and for Christ and to see a higher purpose and long-term benefit than just trying to avoid it until I die. I would be interested to read a work by Dreher that just discusses his views on Christianity and leaves out politics altogether.

![Criddle Charles: That's what you should expect ever [sic] time. I'm proud of her !! (20 likes) / Larry Edward Johnson: The right reaction! The smart reaction, the only reaction! (15 likes) / Bradley Gill: He's probably so offended he is going to go blow himself up.... proving her right. (8 likes) / Tammy Lewton: My reaction would be the same. I did not find her reaction to be unbelievable or outrageous. He is Muslim. Enough said (7 likes) / Paul Mason: No...it's not unbelievable. You are a Muslim and religions that safe harbor criminals and believe your doctrine are idiots. She is perfectly within her God given rights to reject you based upon her beliefs. You go girl! (18 likes) / Raemalynn Webber: If he thinks his people aren't beheaded [sic] Christians, he's blinded. (2 likes) / Vance Kahle: I think the guy is a creep, not because he's Muslim, but because he's filming himself asking women out. What was his purpose with that? Just weird. She's an idiot--some random guy comes up to her, flatters her, and she has no problem with him until he tells her that he's a Muslim? If she didn't get the creep vibe from him prior to that...idiot (6 likes, 5 replies) / George W. Gascon: She is smart Kareem of Wheat! It is unbelievable how Muslims disrespect women so why is he so surprised? (2 likes)](/uploads/4/9/4/8/49486603/8488913-orig_orig.png)

![Todd Quick: This is whats [sic] wrong the LEFT and Muslims. They get mad at the people who hate muslims FOR REASONS and don't understand why? Talk to your Muslim people to stop being terrorist and there wont be any problems for you. (7 likes) / Kayleigh Brianne: I think her reaction was uncalled for and these comments are terrible. Not every Muslim person is bad. Let's not condemn people for their religion but for their actions. (10 likes, 15 replies) / Madelaine Snider-O'Neill: Dump him Girl he has no respect for woman!!!!! (14 likes) / Gilda Mercedes VargasTelleria: She did the right thing! Creepy and stupid! Oh and Muslim! Ugh! / Stephen Signorelli: Her reaction was the best, priceless, muslims are the scum of the earth ! (3 likes) / Gilbert Mansour: good muslim are died [sic] muslim! (11 likes, 8 replies) / Jeff Malcolm: so whats the problem with her reaction... (3 likes) / Audrey McGarty Bera: I think she was correct in her comments and reaction. Good for her (5 likes) / Ramses Soto-Navarro: easy, become an atheist, and don't ever again say that you are muslim. you'll miss out on a lot of good things in life. seriously the word muslim sucks right now. i'm not a racist, just realistic.](/uploads/4/9/4/8/49486603/1053128-orig_orig.png)

![Aleksandra Karasic: lying cheating wife beating hateful pos that what he is and all muslims (1 like) / Gary Joe: Wow really you people are all stupid and racist not all Muslims kill people Jackasses for sure (8 likes, 7 replies) / Anthony Sharon Stankus: I don't see any difference between muslims and nazis (9 likes) / Cean Kish: oh, so all muslims are evil like ISIS [Daesh]? so i guess that makes all christians apart [sic] of the kkk (1 like, 15 replies) / Emmylee Jamesyn Crosby: muslim's have no problem owning their wives beating their wives and children are owned... we have enough abuse in our country!!! (2 likes) / Richard D. Hecht: Her reaction was quite reasonable (5 likes) / Glenn Colley: It is a religion of hate, hate Christians, hate Jews, hate anyone not muslim, hate each other if they are not of the same group. Hate = killing! (2 likes) / Ed Williams: their bible says it all,kill all those who dont believe like they do (4 likes) / Liz Hada: The reaction of this woman and the comments on this post make me so sad. People are so ignorant. (6 likes, 14 replies)](/uploads/4/9/4/8/49486603/2853868-orig_orig.png)