I wrote this for HubPages in February 2013 back when I still had delusions of making money that way. I knew it wouldn't convert anybody, but hoped that it would clear away some weeds so that seeds could be planted, by disabusing people of the notion that The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints was too absurd to give even a moment's consideration. No sooner had I published it then, as predictably as the sunrise, an ex-Mormon came along and condescendingly told me to open my mind and free myself. I wanted to just ignore her but I thought, No, dang it, this is my article and I'm not going to run and hide all the time. I debated with her for a bit, during which time she brought up points that I had already addressed in the article and purported to diagnose the psychological issues that prevented me from agreeing with her, before we reached an amicable settlement and went our separate ways. Over the next few years, a few more critics spectactularly misread my essay but I deleted their spammy comments because life is short. I'm no longer a Mormon but I stand by the general thesis of this essay. It reminds me that I wasn't stupid for believing and not everyone is stupid for continuing to believe. (Yes, some Mormons are dumber than dirt.)

How Can Any Intelligent Person Be a Mormon?

By C. Randall Nicholson

“If a substantial number of sane and intelligent people believe something that seems to you utterly without sense, the problem probably lies with you, for not grasping what it is about that belief that a lucid and reasonable person might find plausible and satisfying.” - Daniel C. Peterson, Latter-day Saint scholar

"But not on the 'Recovery' board. Here all intelligent, right-thinking, and honest people agree with absolute certitude that Mormonism is not simply false, but so manifestly absurd that anyone who believes in it is a liar or an idiot." - William J. Hamblin, Latter-day Saint scholar

"But not on the 'Recovery' board. Here all intelligent, right-thinking, and honest people agree with absolute certitude that Mormonism is not simply false, but so manifestly absurd that anyone who believes in it is a liar or an idiot." - William J. Hamblin, Latter-day Saint scholar

As a member of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints being raised in upstate New York, I quickly grew accustomed to my beliefs being mocked by nonmember friends. As I prepared to graduate high school a musical was released wherein my beliefs were mocked on the Broadway stage. On one occasion an atheist acquaintance said to me, “You seriously believe in a religion that's just as stupid as Scientology? Grow some self-thought, you dumb [expletive]."

This latter brand of mockery tends to be extremely common in the safety and anonymity of the Internet, and it never ceases to bemuse me. Here's a news flash: I make no claims to be an intellectual, or a scholar, or a scriptorian, but I'm a smart person and I know how to think. I don't believe what I believe because of my parents, or my Sunday School teachers, or the General Authorities, or anyone else. I believe what I believe because I've grown self-thought. I've studied it, pondered it, applied it, questioned it, dissected it, applied it again, and come away satisfied. But a lot of people won't even consider that possibility because, come on, this is Mormonism we're talking about!

It's far beyond the scope of this article to address all the criticisms of the Church, and that would be a waste of time anyway as most of them have been addressed several times before (see for example these websites). Nor am I attempting to prove my beliefs to anyone. That would be impossible, and undesirable in any case, seeing as the gospel is meant to be accepted on faith. I simply hope to illustrate how, in my view, intelligent people find satisfaction in the Church. People like these scholars, for instance.

This latter brand of mockery tends to be extremely common in the safety and anonymity of the Internet, and it never ceases to bemuse me. Here's a news flash: I make no claims to be an intellectual, or a scholar, or a scriptorian, but I'm a smart person and I know how to think. I don't believe what I believe because of my parents, or my Sunday School teachers, or the General Authorities, or anyone else. I believe what I believe because I've grown self-thought. I've studied it, pondered it, applied it, questioned it, dissected it, applied it again, and come away satisfied. But a lot of people won't even consider that possibility because, come on, this is Mormonism we're talking about!

It's far beyond the scope of this article to address all the criticisms of the Church, and that would be a waste of time anyway as most of them have been addressed several times before (see for example these websites). Nor am I attempting to prove my beliefs to anyone. That would be impossible, and undesirable in any case, seeing as the gospel is meant to be accepted on faith. I simply hope to illustrate how, in my view, intelligent people find satisfaction in the Church. People like these scholars, for instance.

How Can Any Intelligent Person Believe Something so Weird?

“Mormons are really weird. Y'see, Mormons believe that Joseph Smith got gold plates from an angel on a hill, when everyone knows that Moses got stone tablets from a burning bush on a mountain.” - Stephen Colbert, comedian (Incidentally, Mormons also believe the Moses story)

Latter-day Saints are derided for such things as wearing “magic underwear” (actually, most of us make no claim that temple garments have supernatural powers), believing that God lives on a planet called Kolob (actually, it's a planet near a star called Kolob), and believing that the Garden of Eden was in Jackson County, Missouri (actually, that one's accurate). To which I say, so what? Weirdness only means that something is unorthodox, in this case because it differs from longer-established faith traditions and is adhered to by only a small percentage of the national and world populations. I repeat, so what?

For some perhaps the biggest issue is one considered to be not only "weird" but arrogant and blasphemous as well, and that's the doctrine of "exaltation", known to scholars as theosis or deification - in other words, becoming gods. Yet this general idea is hardly foreign to C.S. Lewis, a few dozen other Christian scholars past and present, Orthodox Christianity (comprising between 200 and 300 million people), and the Bible itself. Obviously it's doubtful that these people share the particular Mormon view of theosis, and the interpretation of the Bible verses could be (and has been) debated for hours. The point is that the concept of becoming gods, whatever that may entail, is hardly as "weird" as critics make it out to be.

For some perhaps the biggest issue is one considered to be not only "weird" but arrogant and blasphemous as well, and that's the doctrine of "exaltation", known to scholars as theosis or deification - in other words, becoming gods. Yet this general idea is hardly foreign to C.S. Lewis, a few dozen other Christian scholars past and present, Orthodox Christianity (comprising between 200 and 300 million people), and the Bible itself. Obviously it's doubtful that these people share the particular Mormon view of theosis, and the interpretation of the Bible verses could be (and has been) debated for hours. The point is that the concept of becoming gods, whatever that may entail, is hardly as "weird" as critics make it out to be.

How Can Any Educated or Informed Person be a Mormon?

“I am not astonished that infidelity prevails to a great extent among the inhabitants of the earth, for the religious teachers of the people advance many ideas and notions for truth which are in opposition to and contradict facts demonstrated by science, and which are generally understood.” - Brigham Young, second President of the Church

An increasingly common and more than slightly bigoted assumption these days is that religious people must be ignorant, for if they learn the facts, they inevitably abandon religion. Yet as Latter-day Saints become more educated, their level of church attendance and other religiosity factors increase. Obviously we can't judge their level of faith or commitment even on these factors, but they're a good indication. And this shouldn't come as much of a surprise seeing as the Church, for its part, places a lot of emphasis on secular education in its theology and even provides a Perpetual Education Fund for impoverished members throughout the world.

The availability of information on the Internet, though often lauded by critics as the Church's undoing (and indeed responsible for more than a few people leaving the Church), was found in a case study by the Cumorah Foundation to have virtually no net effect on overall membership growth or decline. (The Cumorah Foundation is of course pro-Mormon, but many of its other observations on international church growth are somewhat less than flattering.) The nineteenth-century arrival of the railroad in Utah, which ended the Saints' isolation from the United States, was similarly predicted to herald the end of the Church. Similarly, it did not.

Contrary to popular belief and despite the sometimes forcefully written views of many General Authorities through the years, the Church doesn't have a doctrine against, say, organic evolution. Pro-evolution Saints ranging from BYU professors to yours truly have pontificated on questions raised by a meshing of science and theology. (I'm not saying that creationists are necessarily unintelligent – I was one for a couple years, so I know where many of them are coming from. But mainstream Christianity's real or perceived hostility towards science is a major factor in its decline, so this is a big deal to me.)

I recommend the book Reflections of a Scientist by the late Mormon chemist Henry Eyring (father of Apostle Henry B. Eyring), whose Transition state theory for the rate of chemical reactions failed to win the Nobel Prize because the Committee didn't understand it. He was very intelligent, very educated, and very devout. His views, though expounded at greater length in his book and elsewhere, could probably be summed up in the quote, "Is there any conflict between science and religion? There is no conflict in the mind of God, but often there is conflict in the minds of men."

The availability of information on the Internet, though often lauded by critics as the Church's undoing (and indeed responsible for more than a few people leaving the Church), was found in a case study by the Cumorah Foundation to have virtually no net effect on overall membership growth or decline. (The Cumorah Foundation is of course pro-Mormon, but many of its other observations on international church growth are somewhat less than flattering.) The nineteenth-century arrival of the railroad in Utah, which ended the Saints' isolation from the United States, was similarly predicted to herald the end of the Church. Similarly, it did not.

Contrary to popular belief and despite the sometimes forcefully written views of many General Authorities through the years, the Church doesn't have a doctrine against, say, organic evolution. Pro-evolution Saints ranging from BYU professors to yours truly have pontificated on questions raised by a meshing of science and theology. (I'm not saying that creationists are necessarily unintelligent – I was one for a couple years, so I know where many of them are coming from. But mainstream Christianity's real or perceived hostility towards science is a major factor in its decline, so this is a big deal to me.)

I recommend the book Reflections of a Scientist by the late Mormon chemist Henry Eyring (father of Apostle Henry B. Eyring), whose Transition state theory for the rate of chemical reactions failed to win the Nobel Prize because the Committee didn't understand it. He was very intelligent, very educated, and very devout. His views, though expounded at greater length in his book and elsewhere, could probably be summed up in the quote, "Is there any conflict between science and religion? There is no conflict in the mind of God, but often there is conflict in the minds of men."

How Can Any Intelligent Person Know the Church's Full History and Still Believe?

“[When studying church history] I leave ample room for human perversity. I am not wed to any single, simple version of the past. I leave room for new information and new interpretations. My testimony is not dependent on scholars. My testimony of the eternal gospel does not hang in the balance.” - Davis Bitton, former Assistant Church Historian

As a hobby I study church history extensively from myriad sources, many of them openly hostile towards the Church. One thought often surfaces above all; that it's amazing how badly God's servants are allowed to mess things up without ruining His plans. I've learned a lot of things, good, bad, and ugly. I've learned things that I really wish hadn't happened, things that have upset me for days on end and forced me to reevaluate long-held assumptions. But when all is said and done, as I step back and look at the big picture, I see God's hand over the Church's progress and destiny. I can't honestly believe that it would still be here without divine protection and guidance, considering everything it's been (and still is) up against.

Of course, a few historical issues are more complicated than most. Why, for several decades, did many men in the Church take multiple wives? Why were Saints of African descent barred from the priesthood and temple ordinances between 1847-ish and June 1978? Why doesn't Joseph Smith's translation of the Book of Abraham and its facsimiles match the consensus of modern Egyptologists? These issues are challenging, but after giving them the thought and research they deserve, it's clear to me that none of them is a "smoking gun" that invalidates the Church's truth claims or the evidence in its favor.

The Church is routinely accused of hiding uncomfortable facts about its history. I do disagree with its previous traditional approach to history – while it's under no obligation to routinely share the controversial or disturbing aspects which can be found in any human history, I think it's erred too far in the other direction – and many, as mentioned with regard to the internet, have lost their faith and left the Church as a result. However, I don't think the charge of "hiding" them can be sustained. Many of the “hidden” facts are found occasionally in church publications through the years, while virtually all of them are present in unofficial works by faithful members who remain in good standing.

“There are several different elements of that,” Apostle Dallin H. Oaks once said. “One element is that we’re emerging from a period of history writing within the Church [of] adoring history that doesn’t deal with anything that’s unfavorable, and we’re coming into a period of 'warts and all' kind of history. Perhaps our writing of history is lagging behind the times, but I believe that there is purpose in all these things — there may have been a time when Church members could not have been as well prepared for that kind of historical writing as they may be now... there is no way to avoid this criticism. The best I can say is that we’re moving with the times, we’re getting more and more forthright, but we will never satisfy every complaint along that line and probably shouldn’t.”

Of course, a few historical issues are more complicated than most. Why, for several decades, did many men in the Church take multiple wives? Why were Saints of African descent barred from the priesthood and temple ordinances between 1847-ish and June 1978? Why doesn't Joseph Smith's translation of the Book of Abraham and its facsimiles match the consensus of modern Egyptologists? These issues are challenging, but after giving them the thought and research they deserve, it's clear to me that none of them is a "smoking gun" that invalidates the Church's truth claims or the evidence in its favor.

The Church is routinely accused of hiding uncomfortable facts about its history. I do disagree with its previous traditional approach to history – while it's under no obligation to routinely share the controversial or disturbing aspects which can be found in any human history, I think it's erred too far in the other direction – and many, as mentioned with regard to the internet, have lost their faith and left the Church as a result. However, I don't think the charge of "hiding" them can be sustained. Many of the “hidden” facts are found occasionally in church publications through the years, while virtually all of them are present in unofficial works by faithful members who remain in good standing.

“There are several different elements of that,” Apostle Dallin H. Oaks once said. “One element is that we’re emerging from a period of history writing within the Church [of] adoring history that doesn’t deal with anything that’s unfavorable, and we’re coming into a period of 'warts and all' kind of history. Perhaps our writing of history is lagging behind the times, but I believe that there is purpose in all these things — there may have been a time when Church members could not have been as well prepared for that kind of historical writing as they may be now... there is no way to avoid this criticism. The best I can say is that we’re moving with the times, we’re getting more and more forthright, but we will never satisfy every complaint along that line and probably shouldn’t.”

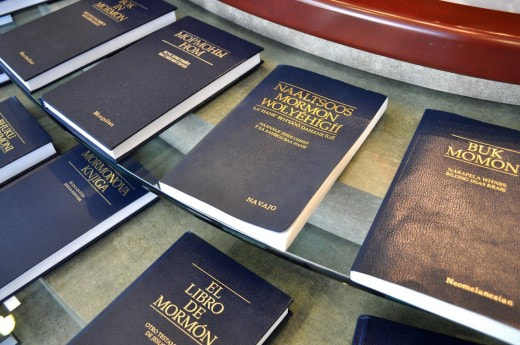

How Can Any Intelligent Person Believe in the Book of Mormon?

"The Book of Mormon has not been universally considered by its critics as one of those books that must be read in order to have an opinion of it." - Thomas F. O'Dea, Catholic sociologist

I find that, with the exception of ex-Mormons, most people who mock Joseph Smith's claims haven't even bothered to review his product. But that doesn't stop them from copying and pasting cherry-picked verses that they've never seen in context, or repeating contrived plagiarism theories that require more faith than the angel explanation (Jeff Lindsay illustrates the inanity of such theories in a satirical skit). I imagine their “logic” goes something like this: there's no such thing as angelic visitations, ergo Joseph Smith obviously wrote the book, ergo there's no reason to actually read it. Yet the challenge offered by Mormon scholar Hugh Nibley to his Book of Mormon students still stands:

“Since Joseph Smith was younger than most of you and not nearly so experienced or well-educated as any of you at the time he copyrighted the Book of Mormon, it should not be too much to ask you to hand in by the end of the semester (which will give you more time than he had) a paper of, say, five to six hundred pages in length. Call it a sacred book if you will, and give it the form of a history. Tell of a community of wandering Jews in ancient times; have all sorts of characters in your story, and involve them in all sorts of public and private vicissitudes; give them names--hundreds of them--pretending that they are real Hebrew and Egyptian names of circa 600 b.c.; be lavish with cultural and technical details--manners and customs, arts and industries, political and religious institutions, rites, and traditions, include long and complicated military and economic histories; have your narrative cover a thousand years without any large gaps; keep a number of interrelated local histories going at once; feel free to introduce religious controversy and philosophical discussion, but always in a plausible setting; observe the appropriate literary conventions and explain the derivation and transmission of your varied historical materials.

“Above all, do not ever contradict yourself! For now we come to the really hard part of this little assignment. You and I know that you are making this all up--we have our little joke--but just the same you are going to be required to have your paper published when you finish it, not as fiction or romance, but as a true history! After you have handed it in you may make no changes in it (in this class we always use the first edition of the Book of Mormon); what is more, you are to invite any and all scholars to read and criticize your work freely, explaining to them that it is a sacred book on a par with the Bible. If they seem over-skeptical, you might tell them that you translated the book from original records by the aid of the Urim and Thummim--they will love that! Further to allay their misgivings, you might tell them that the original manuscript was on golden plates, and that you got the plates from an angel. Now go to work and good luck!"

The oft-parroted claim that there's “not a shred” of outside evidence for the Book of Mormon deserves only scorn. Clearly its progenitors confuse “evidence” with “proof”. Indeed, I'd agree that there's not a shred of secular proof for the Book of Mormon. However, even the most dedicated critic should be able to admit that there's evidence for it. There's evidence for every proposition imaginable, whether it's true or not. Does the sun revolve around the Earth? Of course not. Is there evidence that the sun revolves around the Earth? Of course; otherwise people wouldn't have believed it for so long. The sun's apparent path through the sky is evidence even though the proposition is false.

Space and time don't permit even a cursory overview of all the evidences for the Book of Mormon, besides which I've already said that I'm not trying to prove my beliefs. Interested readers, however, are welcome to read this page or the book Mormon's Codex by Dr. John Sorenson. Of course, even if such evidences could prove the book's historicity, what would that accomplish? We know the Bible describes many people and places that actually existed, yet that doesn't compel everyone to also accept the miracles described therein or even the existence of God. (If it did, then archaeological evidence would prove the Doctrine and Covenants true, which would in turn prove the Book of Mormon.)

“Since Joseph Smith was younger than most of you and not nearly so experienced or well-educated as any of you at the time he copyrighted the Book of Mormon, it should not be too much to ask you to hand in by the end of the semester (which will give you more time than he had) a paper of, say, five to six hundred pages in length. Call it a sacred book if you will, and give it the form of a history. Tell of a community of wandering Jews in ancient times; have all sorts of characters in your story, and involve them in all sorts of public and private vicissitudes; give them names--hundreds of them--pretending that they are real Hebrew and Egyptian names of circa 600 b.c.; be lavish with cultural and technical details--manners and customs, arts and industries, political and religious institutions, rites, and traditions, include long and complicated military and economic histories; have your narrative cover a thousand years without any large gaps; keep a number of interrelated local histories going at once; feel free to introduce religious controversy and philosophical discussion, but always in a plausible setting; observe the appropriate literary conventions and explain the derivation and transmission of your varied historical materials.

“Above all, do not ever contradict yourself! For now we come to the really hard part of this little assignment. You and I know that you are making this all up--we have our little joke--but just the same you are going to be required to have your paper published when you finish it, not as fiction or romance, but as a true history! After you have handed it in you may make no changes in it (in this class we always use the first edition of the Book of Mormon); what is more, you are to invite any and all scholars to read and criticize your work freely, explaining to them that it is a sacred book on a par with the Bible. If they seem over-skeptical, you might tell them that you translated the book from original records by the aid of the Urim and Thummim--they will love that! Further to allay their misgivings, you might tell them that the original manuscript was on golden plates, and that you got the plates from an angel. Now go to work and good luck!"

The oft-parroted claim that there's “not a shred” of outside evidence for the Book of Mormon deserves only scorn. Clearly its progenitors confuse “evidence” with “proof”. Indeed, I'd agree that there's not a shred of secular proof for the Book of Mormon. However, even the most dedicated critic should be able to admit that there's evidence for it. There's evidence for every proposition imaginable, whether it's true or not. Does the sun revolve around the Earth? Of course not. Is there evidence that the sun revolves around the Earth? Of course; otherwise people wouldn't have believed it for so long. The sun's apparent path through the sky is evidence even though the proposition is false.

Space and time don't permit even a cursory overview of all the evidences for the Book of Mormon, besides which I've already said that I'm not trying to prove my beliefs. Interested readers, however, are welcome to read this page or the book Mormon's Codex by Dr. John Sorenson. Of course, even if such evidences could prove the book's historicity, what would that accomplish? We know the Bible describes many people and places that actually existed, yet that doesn't compel everyone to also accept the miracles described therein or even the existence of God. (If it did, then archaeological evidence would prove the Doctrine and Covenants true, which would in turn prove the Book of Mormon.)

How Can Any Intelligent Person Have Faith?

"Bearing in mind that faith and reason are necessary companions, consider the following analogy: faith and reason are like the two wings of an aircraft. Both are essential to maintain flight. If, from your perspective, reason seems to contradict faith, pause and remember that our perspective is extremely limited compared with the Lord’s." - Marcus B. Nash, Seventy

So far I've focused on more or less secular ways of looking at the Church, but I'm pleased to say that I don't rely exclusively or even primarily on them, and neither does any other Latter-day Saint I'm aware of. Because secular concepts of reason and empirical evidence have brought us uncountable increases in scientific knowledge and advances in life-improving technology – and in part, too, because these increases have sometimes been vehemently opposed by religious people – many people decide it's the only way to look at things.

But faith is designed for different purposes entirely. There's some overlap, but for the most part the two methods fill different roles, and many intelligent people find them quite compatible. Faith didn't put men on the moon or discover the polio vaccine. But as much as I love the wonders of the modern age, and as much as I would probably hate to live in any previous century without them, they would provide very little comfort to me if I didn't know what would happen after death. If I thought that nothing I did mattered and that I would someday face permanent oblivion, as would the entire human race and the planet Earth and eventually the entire universe, I wouldn't see the point in another day.

And that's coming from someone with a relatively good life! “But,” Daniel C. Peterson might say, “the vast majority of the world’s population is not so situated, and, for them, atheism, if true, is very bad news indeed. Most of the world’s population, historically and still today, does not live, well fed and well traveled, to a placid old age surrounded by creature comforts. Most of the world has been and is like the favelas of Rio de Janeiro, the slums of Cairo, the backward rural villages of India, the famine-ridden deserts of northeastern Africa, the war-ravaged towns of the southern Sudan and of Rwanda. If there is going to be a truly happy ending for the millions upon millions of those whose lives have been blighted by torture, starvation, disease, rape, and murder, that ending will have to come in a future life. And such a future life seems to require a God.”

Obviously faith in this broad sense applies equally well to any religion, and obviously (as Brother Peterson acknowledges) simply hoping for goodness and justice in the universe doesn't make it the case. As to the first, I find that for me the Church's doctrines are the most logical, that they give the most cohesive and satisfying answers to the questions of life. (I won't go into specifics here because, again, I'm not trying to prove my beliefs, and I don't want to criticize the beliefs of others.) As to the second, I think most people of faith would agree with me that it isn't blind. It isn't a matter of choosing something unprovable at random and devoting oneself to it. Various people explain the process differently, but for me the best explanation is still that offered by Alma, an ancient American prophet:

"But behold, if ye will awake and arouse your faculties, even to an experiment upon my words, and exercise a particle of faith, yea, even if ye can no more than desire to believe, let this desire work in you, even until ye believe in a manner that ye can give place for a portion of my words. Now, we will compare the word unto a seed. Now, if ye give place, that a seed may be planted in your heart, behold, if it be a true seed, or a good seed, if ye do not cast it out by your unbelief, that ye will resist the Spirit of the Lord, behold, it will begin to swell within your breasts; and when you feel these swelling motions, ye will begin to say within yourselves—It must needs be that this is a good seed, or that the word is good, for it beginneth to enlarge my soul; yea, it beginneth to enlighten my understanding, yea, it beginneth to be delicious to me."

I recommend reading the whole passage, because it's all great but too long to reprint here. This is basically the pattern I've followed. I said to myself, "Okay, these doctrines make sense to me, and I feel really good when I go to church or study the scriptures or pray." So I kept going to church and studying the scriptures and praying. I kept the commandments and tried to continually improve myself while recognizing that only in Christ would my imperfections be swallowed up. Unlike many, I've never specifically prayed to know whether the Book of Mormon is true or whether Joseph Smith was a prophet. Perhaps I should have. But my experiences have brought me to that conclusion anyway.

It works for me. God's presence and intervention in my life is tangible. He's gotten me through so much - a social life plagued by high-functioning autism, an emotional life plagued by chronic depression, and an academic life plagued by worsening procrastination and insomnia, to name the most obvious and prolonged examples. His influence not only calms me in times of distress but guides me to do the right things and, when I've ignored said guidance and done the wrong things anyway, arranges events so that I get through every challenge alive (figuratively speaking) when reason dictates that I shouldn't be able to unless I'm really, really, really lucky. If I didn't trust in God and this church, my life would be an utter mess, if indeed I was still alive (literally speaking) at all. God loves all His children, and can and does act in their lives regardless of religious affiliation, but I owe my knowledge of and relationship with Him to this church that prioritizes prayer and personal revelation like no other.

In a sense, this almost does sound scientific; testing a hypothesis (faith; the seed) and gathering evidence for it (the results of exercising faith; the fruit). But it differs significantly in that a person's results are personal and can't be critiqued for falsified by another. That's why atheists hate it so much and denounce it as stupid. But I see it as a beautiful thing; faith is an individual matter that each person needs to ponder and investigate for themselves. Naturally, we can and should help each other in the process, which is why Mormons hold fast and testimony meeting. But ultimately every person's faith and spiritual path is between them and God. No one can take that away from them and no one can deny the joy, the peace, or the blessings that they experience in their lives as a result.

Personally, I see nothing unintelligent about that.

Read more of my essays here.

But faith is designed for different purposes entirely. There's some overlap, but for the most part the two methods fill different roles, and many intelligent people find them quite compatible. Faith didn't put men on the moon or discover the polio vaccine. But as much as I love the wonders of the modern age, and as much as I would probably hate to live in any previous century without them, they would provide very little comfort to me if I didn't know what would happen after death. If I thought that nothing I did mattered and that I would someday face permanent oblivion, as would the entire human race and the planet Earth and eventually the entire universe, I wouldn't see the point in another day.

And that's coming from someone with a relatively good life! “But,” Daniel C. Peterson might say, “the vast majority of the world’s population is not so situated, and, for them, atheism, if true, is very bad news indeed. Most of the world’s population, historically and still today, does not live, well fed and well traveled, to a placid old age surrounded by creature comforts. Most of the world has been and is like the favelas of Rio de Janeiro, the slums of Cairo, the backward rural villages of India, the famine-ridden deserts of northeastern Africa, the war-ravaged towns of the southern Sudan and of Rwanda. If there is going to be a truly happy ending for the millions upon millions of those whose lives have been blighted by torture, starvation, disease, rape, and murder, that ending will have to come in a future life. And such a future life seems to require a God.”

Obviously faith in this broad sense applies equally well to any religion, and obviously (as Brother Peterson acknowledges) simply hoping for goodness and justice in the universe doesn't make it the case. As to the first, I find that for me the Church's doctrines are the most logical, that they give the most cohesive and satisfying answers to the questions of life. (I won't go into specifics here because, again, I'm not trying to prove my beliefs, and I don't want to criticize the beliefs of others.) As to the second, I think most people of faith would agree with me that it isn't blind. It isn't a matter of choosing something unprovable at random and devoting oneself to it. Various people explain the process differently, but for me the best explanation is still that offered by Alma, an ancient American prophet:

"But behold, if ye will awake and arouse your faculties, even to an experiment upon my words, and exercise a particle of faith, yea, even if ye can no more than desire to believe, let this desire work in you, even until ye believe in a manner that ye can give place for a portion of my words. Now, we will compare the word unto a seed. Now, if ye give place, that a seed may be planted in your heart, behold, if it be a true seed, or a good seed, if ye do not cast it out by your unbelief, that ye will resist the Spirit of the Lord, behold, it will begin to swell within your breasts; and when you feel these swelling motions, ye will begin to say within yourselves—It must needs be that this is a good seed, or that the word is good, for it beginneth to enlarge my soul; yea, it beginneth to enlighten my understanding, yea, it beginneth to be delicious to me."

I recommend reading the whole passage, because it's all great but too long to reprint here. This is basically the pattern I've followed. I said to myself, "Okay, these doctrines make sense to me, and I feel really good when I go to church or study the scriptures or pray." So I kept going to church and studying the scriptures and praying. I kept the commandments and tried to continually improve myself while recognizing that only in Christ would my imperfections be swallowed up. Unlike many, I've never specifically prayed to know whether the Book of Mormon is true or whether Joseph Smith was a prophet. Perhaps I should have. But my experiences have brought me to that conclusion anyway.

It works for me. God's presence and intervention in my life is tangible. He's gotten me through so much - a social life plagued by high-functioning autism, an emotional life plagued by chronic depression, and an academic life plagued by worsening procrastination and insomnia, to name the most obvious and prolonged examples. His influence not only calms me in times of distress but guides me to do the right things and, when I've ignored said guidance and done the wrong things anyway, arranges events so that I get through every challenge alive (figuratively speaking) when reason dictates that I shouldn't be able to unless I'm really, really, really lucky. If I didn't trust in God and this church, my life would be an utter mess, if indeed I was still alive (literally speaking) at all. God loves all His children, and can and does act in their lives regardless of religious affiliation, but I owe my knowledge of and relationship with Him to this church that prioritizes prayer and personal revelation like no other.

In a sense, this almost does sound scientific; testing a hypothesis (faith; the seed) and gathering evidence for it (the results of exercising faith; the fruit). But it differs significantly in that a person's results are personal and can't be critiqued for falsified by another. That's why atheists hate it so much and denounce it as stupid. But I see it as a beautiful thing; faith is an individual matter that each person needs to ponder and investigate for themselves. Naturally, we can and should help each other in the process, which is why Mormons hold fast and testimony meeting. But ultimately every person's faith and spiritual path is between them and God. No one can take that away from them and no one can deny the joy, the peace, or the blessings that they experience in their lives as a result.

Personally, I see nothing unintelligent about that.

Read more of my essays here.